Can far-sighted architecture make a difference in the forms and future development of our cities, opposing the violent work of destruction of slums imposed in the past? Elisa Minari sought a response to this question in her 2011 graduating thesis project for the Faculty of Architecture of Parma University, which she entered in the first “Next Landmark” international architecture contest, organised by the Floornature portal.

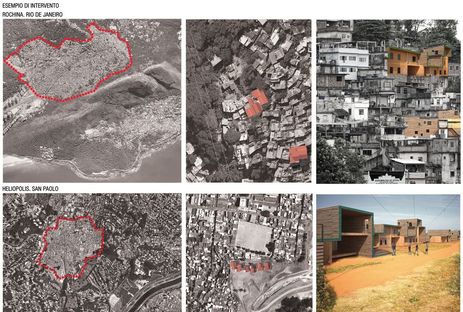

Can far-sighted architecture make a difference in the forms and future development of our cities, opposing the violent work of destruction of slums imposed in the past? Elisa Minari sought a response to this question in her 2011 graduating thesis project for the Faculty of Architecture of Parma University, which she entered in the first “Next Landmark” international architecture contest, organised by the Floornature portal.Elisa Minari looked at settlements which live as parasites on official constructions in the city, known as slums or favelas in different parts of the world and under different conditions of growth, and came to some surprising conclusions. The focus of her research was integration of the slum-dwellers with the people living in the officially constructed city around them, underlining the failure of past policies of marginalisation, rents in the fabric of the city and coercive actions. This is an inescapable phenomenon in some of the cities affected, and in the rest of the world too, in view of the fact that almost a billion people, 32% of the world?s urban population, now live in slums.

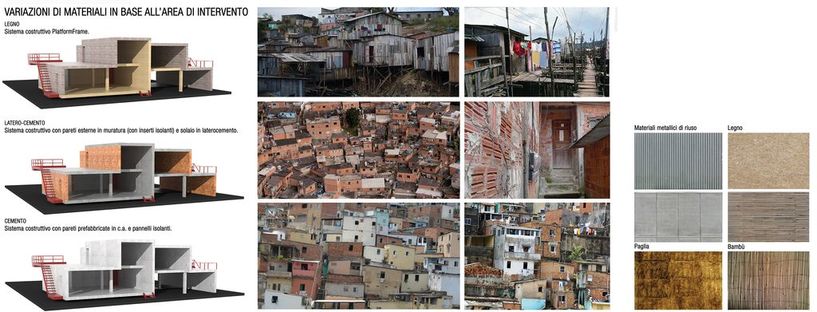

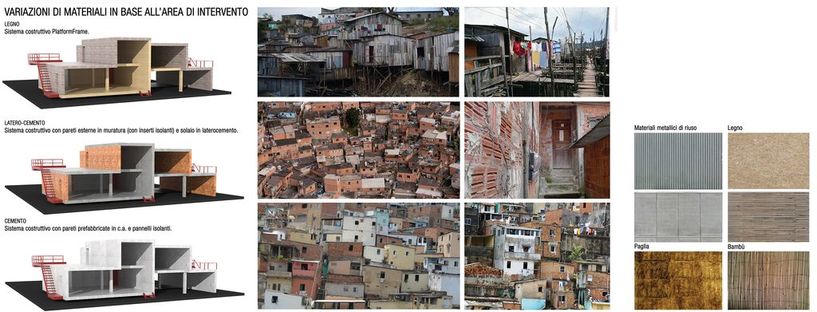

These overwhelming figures reveal that the issue should be of concern to humanity as a whole, encouraging us to come up with a model of architecture which can replace or supplement existing models on the basis of the fact that the slum-dwellers have the same needs as the rest of us, at least when it comes to minimal requirements, self-determination of what they own and participation in building it.

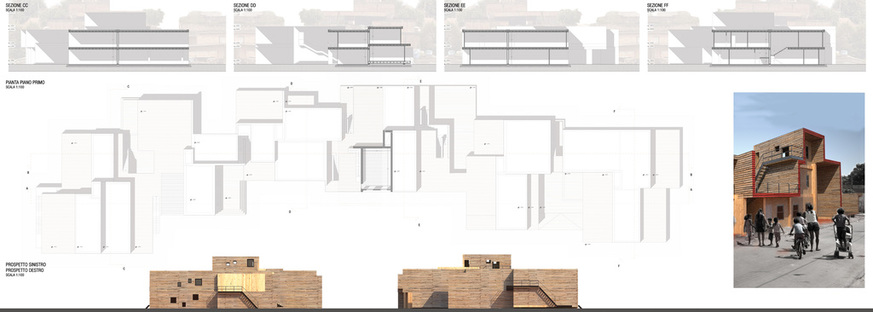

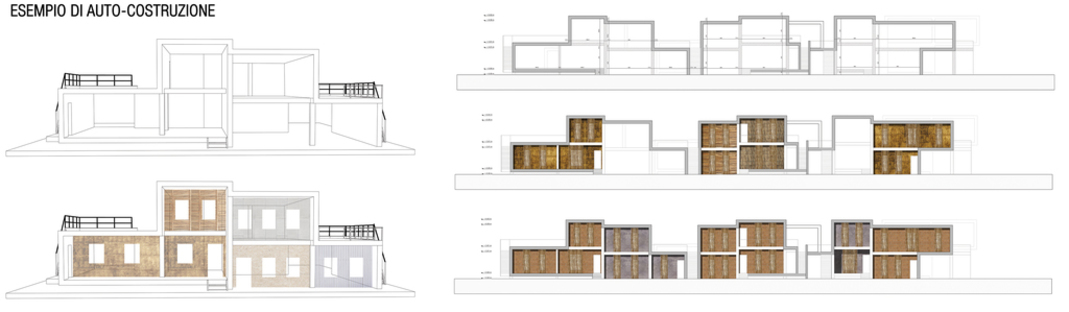

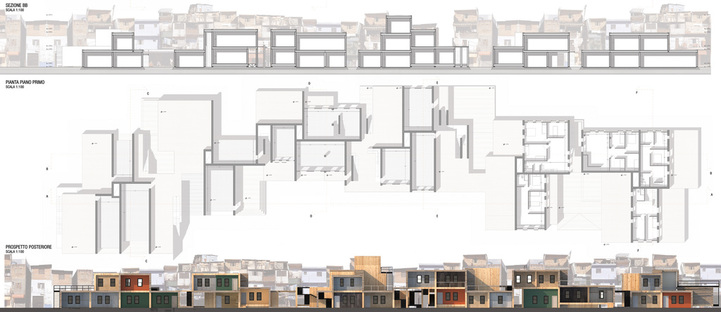

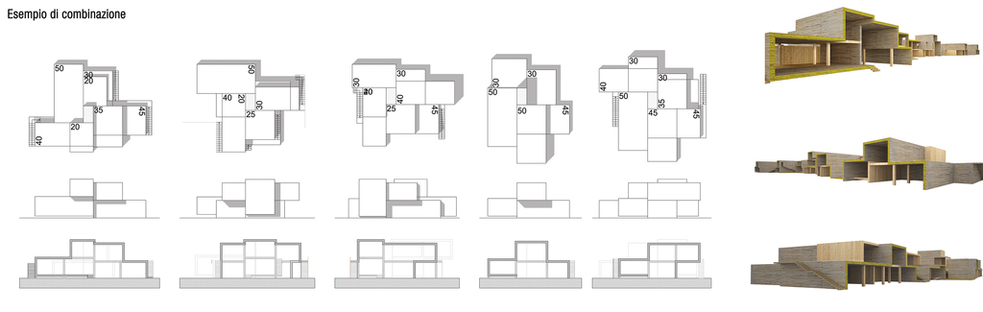

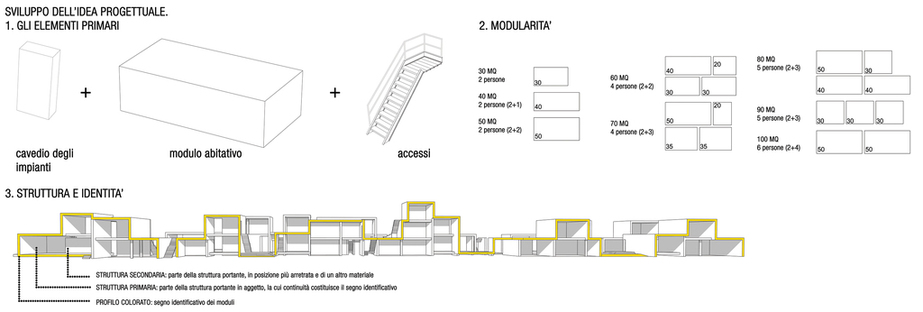

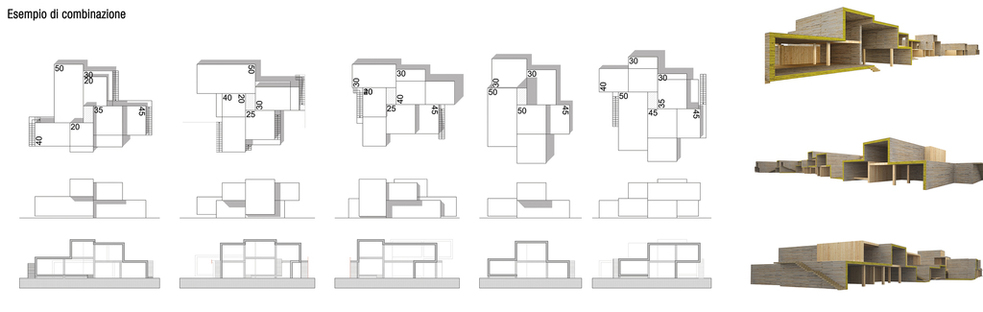

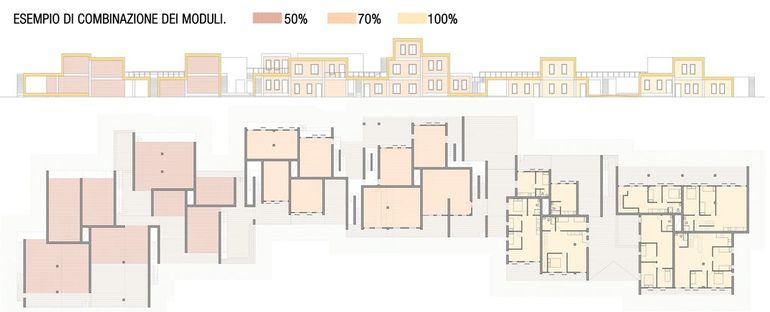

In the wake of the Favela-Bairro programme in Rio de Janeiro in 1993, the first public housing project oriented towards integration and aimed at transforming slums into proper city neighbourhoods, policy has changed radically, starting out with the concept that parasitic settlements should not be viewed as mistakes to be erased but stages in the process of evolution of our cities. A focus on the people who live in the slums, the people who have inherited and in turn contributed to their own homes in the slums as citizens, not just squatters illegally occupying land and buildings, is a key concept in a number of participatory planning projects which provided the model for Elisa Minari?s development of a system of homes built by the people who live in them. The living units pick up on compositional concepts which are already applied in spontaneous construction of slums, such as regular units, easily reproducible on a large scale, prefabrication and adaptability.

Contemplating both processes of restoration and reconstruction from scratch, the project does not evict the inhabitants but gets them involved in the process of reclaiming the land they live on, deciding how much of the work they want to do themselves on the unit they purchase: 50%, 70% or 100%.

Mara Corradi