12-02-2021

31/44 Architects: Red House in East Dulwich, London

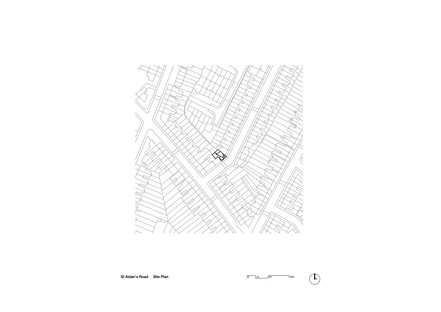

31/44 Architects is the unusual name of the architectural studio operated by William Burges, James Jeffries and Stephen Davies in the Netherlands and England with a special vocation for small, detailed residential projects. Completed in 2017, the Red House in London’s East Dulwich is a design gamble on the part of real estate developer Arrant Land, which focuses on developing particularly small and difficult lots in the south of London. Not a traditional Victorian terraced house of the kind common on the outskirts of the British capital, but a volume at the head of a row of terraced houses in a bend in St. Aidans Road.

The unusual circumstances of designing a building with three free sides on the end of a block of homes with the same formal lines inspired 31/44 Architects to make the property stand out from the other terraced houses on the street, creating a landmark that stands out for particular distinguishing features. Their goal was to create a contemporary interpretation of a type of home familiar to anyone living in London, and the Red House became a landmark because the project maintains continuity while representing a new evolution of the homes typical of this all-residential district.

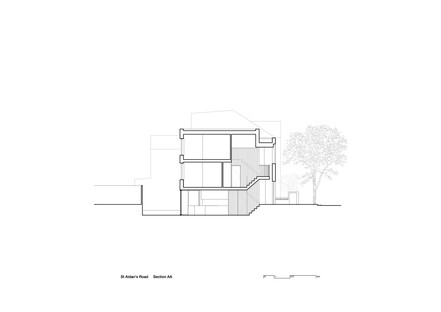

Originally a garage with a courtyard at the back, the volume was renovated to become a house on three levels with courtyards. Analysis of the other terraced houses on the site led the architects to identify a series of distinguishing features and then come up with variations on these. While preserving the alignment of the windows, the main façade conceals the transition from the two levels of the other homes in the row to three levels; the big window on the volume to the side identifies the intermediate floor. The yellow brick typical of these homes, which often creates a unified curtain wall along the entire block, gives way to the deep red brick that gives the house its name.

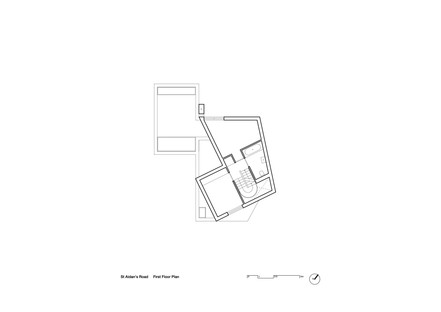

Wishing to maintain the presence of the typical full arch over the door of the terraced houses on the block, the architects open up a door on the side of the house, and convert what would normally be the door into a window of the same proportions. Closed with a single pane of glass, the new window lets light into a double-height hallway interrupted by a sinuous new wooden staircase.

The arch has no decoration and, like all the other windows in the home, has a minimal black frame that does not interfere with letting light in. Decoration reappears in the panel of prefabricated, pigmented concrete forming a large horizonal portion of the façade, where the “houndstooth” pattern recalls the geometric design commonly appearing in the vestibules of Victorian homes. The prefabrication method and non-traditional colour underline the fact that the house is not the product of a restoration project, but of a new interpretation of an element defining the identity of the type of building in question.

The entrance door itself, made of the same dark metal as the window frames, is modestly set back in the shadow of a concrete roof constituting another horizontal sign, a new stringcourse connecting the façade with the wall bordering on the street. Yellow brick comes back here, ideally reconnecting the home with the other façades to demonstrate that the Red House belongs with the other, historic terraced houses on the street.

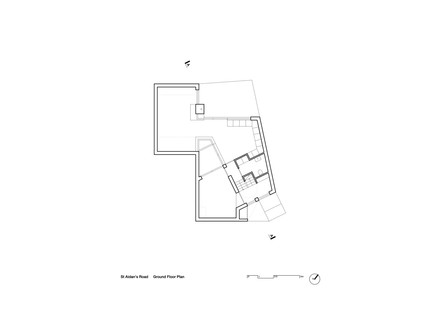

Going in through the double-height entrance hall, we come to a short flight of stairs down to the ground floor, where a single space contains the kitchen, dining room and living room, arranged around two little courtyards. These irregular shapes created to open up the original volume toward the outdoors, surrounded by boundary walls or glass, capture enough light to illuminate the entire ground floor while maintaining the residents’ privacy. This is a new interpretation of the original use of the courtyard at the back of terraced houses, say the architects: a space maintaining continuity with the house itself, intended as storage space, but also for relaxing outdoors.

The last room on the ground floor is the study, lower down than the entrance and more shut-in and private. An internal window captures light from the entrance and ensures visual communication among different points in the home.

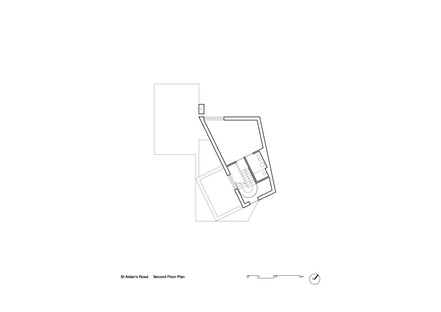

An oak staircase illuminated by the top window on the front of the house leads to the two bedrooms and bathroom on the first floor, and to the master bedroom with its own bathroom and shower on the second floor. 31/44 Architects’ Red House could, in the final analysis, definitely offer a new model for development of boundary houses, in which the tiny size of a lot surrounded by rowhouses represents a limitation, but also offers potential for expression in exclusively residential neighbourhoods.

Mara Corradi

Architects: 31/44 Architects

Location: 37 St. Aidans Road, London SE22 0RN

Gross internal area: 130 sqm

Start on site: December 2015

Date of completion: April 2017

Client: Arrant Land

Architects: 31/44 Architects

Structural Engineers: Elite Designers

Photography: Rory Gardiner, The Modern House