09-09-2022

Rafiq Azam: redevelopment of Rasulbagh Children’s Park, Dhaka

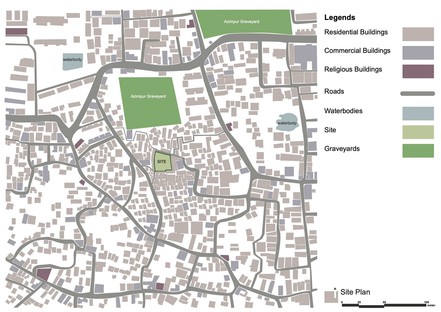

In Rasulbagh, just south of the Azimpur New Graveyard in the centre of old Dhaka, stood one of the city’s last remaining vacant lots, surrounded by residential tower blocks, tiny shops and street market stalls. Despite being referred to as a ‘park’, it was nothing more than a simple open space in a highly urbanised neighbourhood, bounded almost entirely by an enclosure wall, abandoned and neglected, left in an incredibly unsanitary condition and a recurrent stage for violent clashes that had only worsened over the years. This was the picture that Rafiq Azam - a Bengali architect of great renown, both in his country and beyond - was faced with when the Dhaka South City Corporation, the governing body for central Dhaka, awarded him the job of redeveloping the plot a few years ago.

But the story of this Rasulbagh park is a tale as old as time in Dhaka, where many other plots across this vast city also suffer from the lack of coherent planning at the outset, poor maintenance, and the lack of essential facilities for people, from toilets to simple street furniture such as seating and waste bins. Dhaka is located in a region that often bears the brunt of floods during the rainy seasons and its narrow alleyways, which have no proper drainage, quickly become rivers that reach up to half a metre deep. Aside from making life extremely difficult and unsanitary, this situation prevents any form of socialisation from flourishing, transforming what few public spaces there are into no man’s land. According to Rafiq Azam, around 200 years ago, the park was the site of a cemetery owned by a family of ink merchants. Many different factions laid claim to it, but in 1984, the plot was designated a park by the local government, though without establishing any kind of service or maintenance plan for it. Its isolated position due to the inconvenient points of access - alleyways no more than a metre wide - made it fertile ground for social conflicts and a place for families to steer clear of, even though it was paradoxically intended to be a park for children, who would not find entertainment of any kind here.

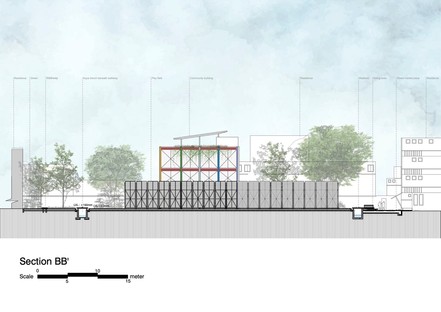

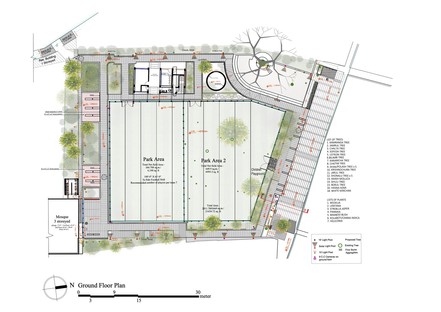

Rafiq Azam’s team at Shatotto, his architecture firm, was faced with a 2800m2 park overrun with dying vegetation, only two points of entry squeezed between buildings, the road and boundary walls in a dire state of disrepair, and a severely dilapidated three-storey building along the western boundary. The mere sight of such a challenging setting drove home the fact that they needed to develop a project within a project. As such, a great deal of time and energy was dedicated to garnering the involvement of the residential and business communities, the elderly and the imam as authority figures, but also local young people, who stood to gain the most benefit. The team’s intention was to foster a certain affection towards the area being redeveloped, with the participatory element stimulating a grassroots care and maintenance process. Before any attempts to redesign the entire area - in the sense of improving its accessibility, functionality and aesthetic appeal - could be undertaken, the team first sought to engage and win over the community, giving the various players some responsibility for maintenance and the organisation of events that would be its lifeblood. The decisive step in this direction was the demolition of the high boundary wall to the north, separating it from the road, which not only prevented direct access, but also severely limited the view of the park from a significant portion of the neighbourhood. With this in mind, the street facing the park was instead incorporated into it and transformed into a promenade with access ramps connected to the nearby alleyways, whilst other ramps were also added to the south-west entrance.

To increase the functionality of the park, Rafiq Azam redeveloped the central area into a sports field, divided into a youth area and a young children’s area, with only permeable screens used as protective fences.

With most of the existing trees having been preserved, the edges of the park were then marked out by planting fruit trees for people to enjoy, as well as more ornamental plants and tall, majestic trees. Some of the most appealing of these include kolaboti, or Indian shot, which can grow up to more than 2 metres tall, hiding the dilapidated walls of the neighbouring buildings and gently blending the park into its surroundings. In the south-west corner, where there is now a repaved access route to the mosque, Rafiq Azam requested four dhaak (flame-of-the-forest) trees, with vibrant, fire-red leaves, given that the species lent its name to the city of Dhaka. The decision to plant trees also serves a functional purpose, namely to absorb excess water, which helps to keep the area as dry as possible during the rainy seasons.

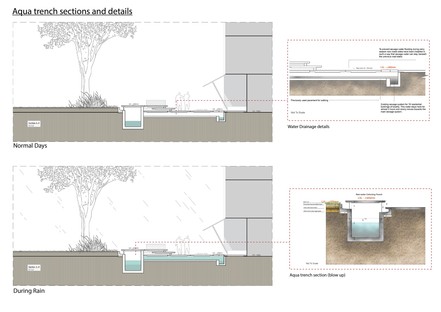

To encourage the community to see the tangible benefits of the park’s redevelopment, there were two especially significant interventions: the first involved creating wastewater collection, filtration and diversion trenches at a height of around half a metre below the new concrete slab paving that marks out the boundaries of the park. All the rainwater collected flows directly into the filtration system, is stored in an underground reservoir, and then distributed via taps that are accessible to all.

The second involved the complete renovation of the crumbling building on the east side, which is now home to a wide array of community services: a women’s club on the ground floor and, on the upper floors, a gym, a common room with a library where young people can study, and a café with roof access.

What was once a hostile no man’s land is now not just a park, but more importantly a fully-fledged community centre, a welcoming ‘town square’ of sorts, where people can pray by the mosque, play together, organise events open to all, and crucially, somewhere women and families can enjoy without fear.

Mara Corradi

Principal Architect: Rafiq Azam https://rafiqazam.com/

Project Architects: Audhora Sharmin, Anika Asif

Associate Architects: Arifur Rahman Kashiq, Sabrina Mehjabeen Ratree, Mantasha Abdullah

Client: Dhaka South City Corporation

Location: Rasulbagh, Lalbagh, Dhaka

Gross useable floor space: 2,506 sqm

Lot size: 2848 sqm

Competition: 2021

Start of work: 2018

Completion of work: 2020

Photographs: Asif Salman, Isabelle Antunes, City Syntax, Shatotto team

Film by Asif Salman

Captions

01-02-03-04-05: Ph City Syntax

06-07-08-09-10-11: Ph Asif Salman

12-13-14-15-16: Ph Shatotto team

17-18-19-20: Before - Ph Shatotto team

21-22-23-24: During - Ph Shatotto team

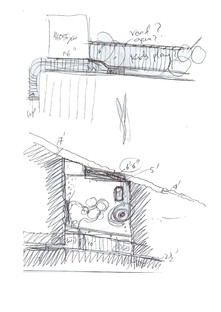

25: Rafq Azam’s sketck