03-12-2021

Rafiq Azam: Mayor Mohammad Hanif Jame Mosque, Dhaka

Rafiq Azam, Shatotto architecture for green living,

Asif Salman, City Syntax, Mike Kelley, Will Scott,

The most recent building designed by Bengalese architect Rafiq Azam, founder of Shatotto Architecture for green living, is a mosque in Azimpur, the district containing one of Dhaka’s biggest cemeteries.

Through the projects built by his studio Shatotto, founded in 1995, Rafiq Azam has become known as an ambassador of Bangladeshi culture in the west, but the architect has never designed a mosque before. Acknowledging Islam not so much as a faith but as a moral authority, as he says, in Mayor Mohammad Hanif Jame Mosque, Azam succeeds in his intent of creating a centre for spirituality that is also a civic centre, a place where the faithful go to pray but are encouraged to stay and socialise.

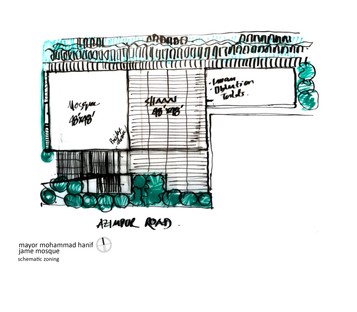

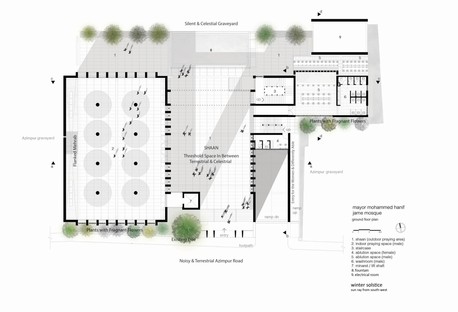

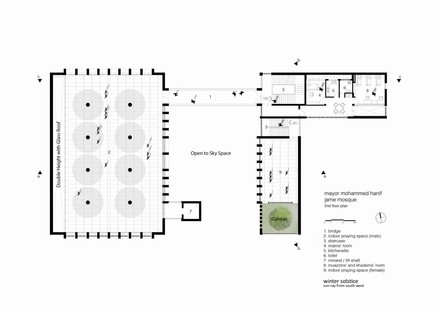

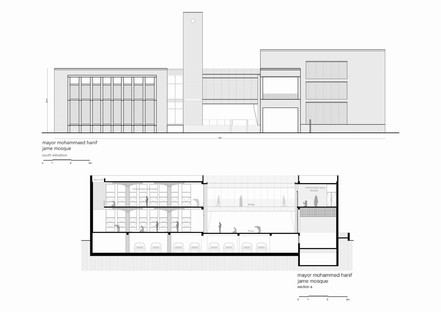

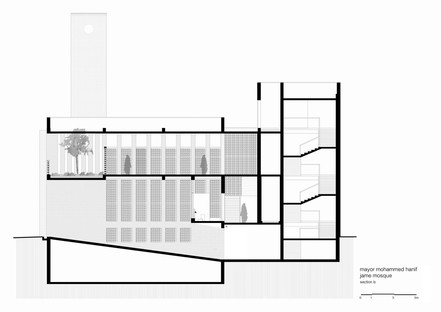

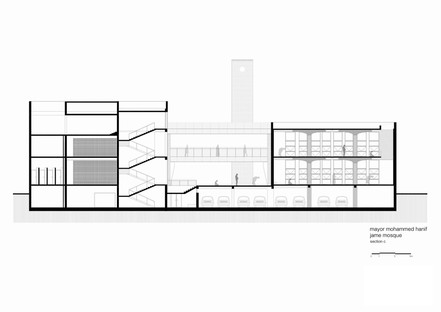

Azimpur is a residential district in the oldest part of the city, founded by the Moghul dynasty more than 400 years ago. Dhaka South City Corporation, the government organisation in Bengal’s capital city that owns the land, commissioned Rafiq Azam to build a new mosque named after Mohammad Hanif, mayor of Dhaka between 1994 and 2002. The building stands beside Azimpur cemetery, between the graves and the road, symbolically and functionally acting as a gateway between the city of the living and the city of the dead. Its layout is effectively designed to be a place of transition, with the “sahn”, an uncovered area traditionally located next to the entrance to the main hall of the mosque, in the centre. The “sahn” divides the site in half, separating the areas where men and women pray, located in a larger volume to the west and a smaller one to the east. The terrace is raised a few steps above the public road, in a privileged position. The north-south axis is interrupted by a glass walkway linking the upper levels of two buildings, that is, the second level of the men’s prayer hall with the offices and rooms of the religious officials to the east, above the area for the men’s ablutions.

In designing a space which is by nature crowded, Rafiq Azam comes up with a layout which is clearly understandable right away: a main passageway offering an intense view through the entrance to the graveyard, and a secondary, more private passageway joining the two blocks of the building on a higher level, framing the view.

The women’s prayer space is clearly smaller and more modest, with its area for ablutions on the ground floor and prayer room on the upper level. But Rafiq Azam reserves one of the features most typically associated with his architectural style for this area: a hanging garden with a big round opening in the roof, inspired by the geometries of Louis Kahn. This device, dramatic, acoustic and climatic all at the same time, accompanies female spirituality in this more intimate prayer room.

Even while distinguishing between the different parts of the building, Azam covers the floor in all the public parts of the mosque with the same grey stone: inside and outside, the slabs are laid with a north-south orientation and a precise rhythm to guide the faithful kneeling in prayer. This ensures that even during the most crowded occasions, such as Eid al-Fitr, celebrating the end of fasting for Ramadan, the “sahn” can be used to provide additional space for prayer.

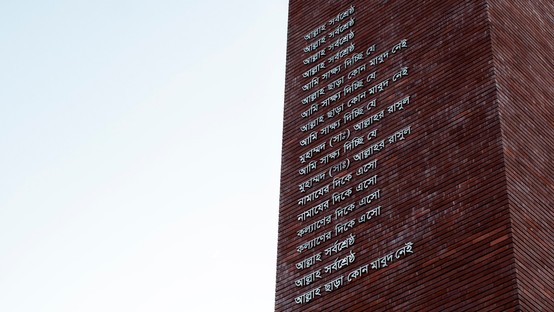

Use of brick, a material which has always been made locally, is a reference to national religious monuments such as Khan Mohammad Mridha and Azam Shah Mosques, built by the Moghuls near Fort Lalbagh, in the centre of Dhaka. The “mashrabiya”, an element shielding against the gaze of passers-by which is very common in the architecture of the Middle East and the Far East, fits into the project to divide the women’s area as well as the men’s area, where it alternates with big panes of glass. As in times gone by, it is also used to improve the natural ventilation of the indoor spaces.

The building has a particularly bold impact inside the main hall, an open space on two levels, supported in the middle by concrete columns stretching upwards and spreading like the foliage of trees to support the floor above. Daylight enters the space through the floor-to-ceiling windows on the eastern side, through the “mashrabiya” and through the opening in the ceiling above the Imam’s space; at twilight, lights come on marking the lines in the floor, along with rings of light illuminating the tops of the columns. In both cases, Rafiq Azam succeeds in designing discrete but functional lighting underlining the quality and importance of the spaces.

The historic and the contemporary come together, and the mosque, crossroads between life and death, between the city and the cemetery, becomes a hospitable space in which to lie down and contemplate, chat with friends, absorb the energy of the place and feel welcome.

Mara Corradi

Architecture Firm: SHATOTTO Architecture for green living

Architect: Rafiq Azam

Design Team: Ibtesa-Moon Adittya, Ikramoon Nisa

Clients: Dhaka South City Corporation

Structural Consultants: Mohammad Akter Hossen, Mostafizur Rahman

Landscape Consultants: Rafiq Azam

MEP Consultants: Mohiminul Islam

Completion year: 2018

Gross Built up Area: 3000 sqm

Location: Azimpur, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Photo credits:

01-18: © Mike Kelley https://www.mpkelley.com/

19-20-21: © City Syntax https://www.citysyntax.com/

22-23: ©Will Scott https://www.willscottphotography.com/

24-25 © Asif Salman https://www.asifsalman.com/

27: Sketch by Rafiq Azam