Well-known in their home country, Mexico, where they have won awards and been featured in exhibitions and publications, TACO taller de arquitectura contextual is an experimental architectural practice combining design with manufacture, participatory conception with actual construction of buildings. Floornature takes a look at their work, starting with the recent Casa del Lago (Lake House) project in Mérida, the capital of Mexico’s Yucatàn state.

The members of TACO consider themselves part of a multidisciplinary workshop with a focus on complex design skills and reinforcement of the identity of the places they work in.

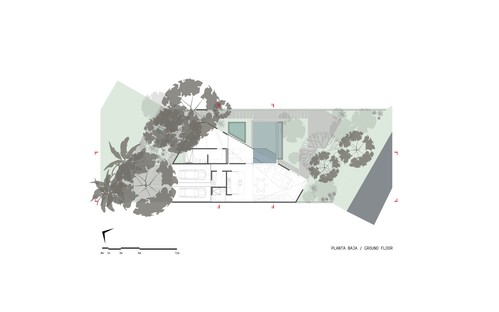

The new home was to be built on a lot abounding in vegetation between a city canal and the street running parallel to it. The home is designed to be a refuge, approaching the natural environment with the goal of becoming a part of it and sheltering the life within it from the noise of the street. To this end, the entrance and most open areas are sheltered by a park created to conceal the spaces outside and inside the home from view. The new landscape design combines the trees that already stood on the land with endemic and ornamental plant species selected by the owners.

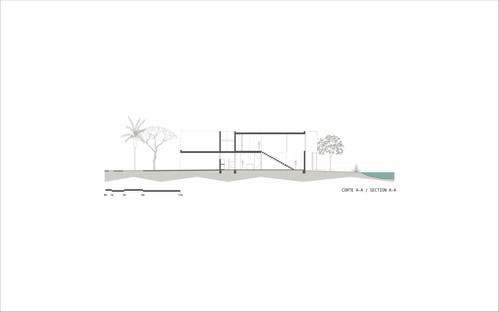

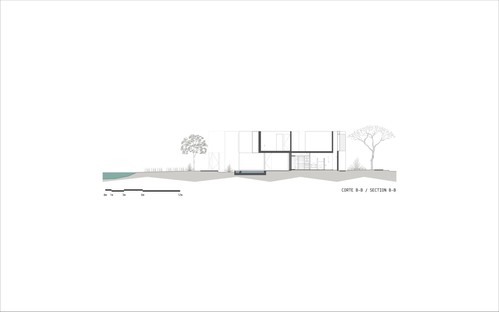

At one end of a luxury housing and holiday home development, to the west, Casa del Lago faces southeast, and all its more public spaces are on this side, where walls of glass connect the living area with the park outside and the bank of the canal.

The layout of the site is marked by a diagonal wall separating the interior from the garden. At the point where this sharp dividing line meets the road, the architects add a pedestrian gateway consisting of an old wooden portal from the owners’ collection of art and crafts, appropriately restored and framed with concrete. Guests wait to be received in the home in a green area with flowerbeds, a foretaste of the bigger garden inside.

But it would be misleading to speak of public and private spaces, as the photographs of the site reveal that there are practically no artificial barriers, but the home is simply sheltered and hidden by the vegetation. The pools alluding to the home’s bond with water make use of the privacy offered by tall fronds at certain points, though the project does not disdain a certain tendency toward voyeurism: from the road, glimpses of the pools of water identify the direction passers-by must look in to see beyond the waterway. This ambiguity accounts for much of the attraction of this home, in which the presence of vegetation is treated as an essential part of the dynamics of everyday life.

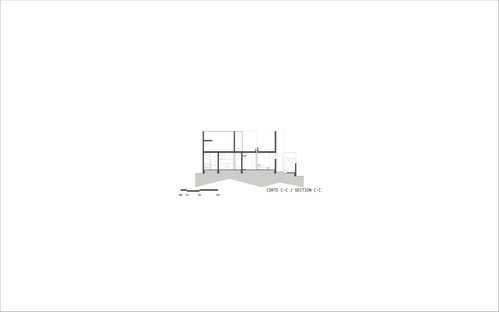

The most important spaces in the home are clearly those intended for socialisation, on the ground floor and with a direct, constant connection with their surroundings. The big double-height living room, kitchen and dining area is the most extreme space in the home, enjoying views over the canal and the park. Its pointed shape seems to channel the natural forces of the site into this spot, where light and air come in from three different points. A system of concrete sunbreaks, common in the Modernist tradition of Central and South America, shades the kitchen from sunlight, creating a shady, well-ventilated corner in which to enjoy a siesta in a hammock.

On the upper level is a loft, connected with the living area, that is used as a bedroom with its own bathroom, while three open terraces on the same level will be covered and furnished for commercial use in the future. At present they are used simply as thinking rooms, solariums or viewpoints, thanks to the openings between the walls, which offer unique hidden viewpoints over the pools and the street. Rather like the “mashrabiyya” in Middle Eastern culture, these constructions also promote natural passive ventilation.

The furniture design combines contemporary elements and details, such as the big open concrete staircase, with items from the owners’ collection of handcrafts to create a rich, colourful interior.

The construction method used is the most common in the area, based on concrete beams and slabs. Basic architectural finishes keep maintenance costs low: the floors inside the home are concrete, as are the slabs cast on site on which built-in furnishings and sunbreaks are assembled. All the walls and low ceilings are finished with a layer of waterproof burnished cement-based stucco, and the pavement of the terraces and external walkways is non-slip bare concrete.

As we noted at the start of this article, TACO taller de arquitectura contextual calls itself a multidisciplinary workshop including not only various design professionals such as architects, designers and civil engineers but craftspeople from various backgrounds, including masons, carpenters and ironmongers, who work together to ensure complete control over all processes. This allows TACO not only to design but to build its own projects.

Mara Corradi

Architects: TACO taller de arquitectura contextual www.arquitecturacontextual.com

Team: Carlos Patrón Ibarra, Alejandro Patrón Sansor, Ana Patrón Ibarra, Estefanía Rivero Janssen, Joaquín Muñoz Olivera.

Client: Private

Location: Mérida, Mexico

Gross useable floor space: 220.00 sqm

Lot surface: 525.00 sqm

Start of work: 2018

Completion of work: 2019

Photographs: © Leo Espinosa