The Aban House, home to the family of architect couple Mohammad Arab and Mina Moeineddini in the historical centre of Isfahan in Iran, is a proposal for a residential model for contemporary Middle Eastern society. The architects drew upon their own experience as well as the heritage of their city, made up of the places, climate and lifestyle typical of Iran. With this home, which has been shortlisted for the Aga Khan Award 2022, they hope to strike up a debate on the controversial issue of people’s quality of life in Iran today.

“The Middle East has undergone with many changes over the past decades, especially in the social structure. In the past two decades in Iran, sanctions, the shadow of war and media hegemony have changed our daily lives. Widespread disappointment on an individual and social scale has led to a wave of migration. Now the important question is what is the role of architecture in this situation? Can architecture play a role in returning hope and peace to society?”.

These are the questions that Mohammad Arab and Mina Moeineddini pondered in the aftermath of the events that forced many of their closest friends and colleagues to flee the country. The pursuit of an answer ultimately led this family to decide to stay and work towards the creation of a new Iranian society from their chosen discipline, the architecture of private spaces. If what Le Corbusier argued a century ago still holds true today - namely that the issue of housing is the key problem of our time and that the balance of society depends upon it - then these two Iranian architects, co-founders of USE Studio, have decided to make their home an experimental model with a view to solving it.

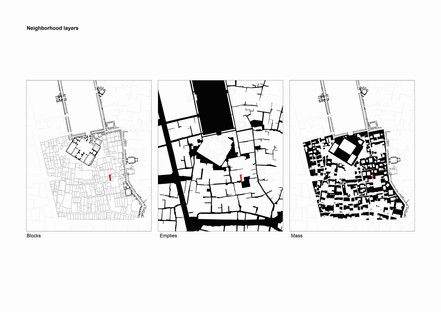

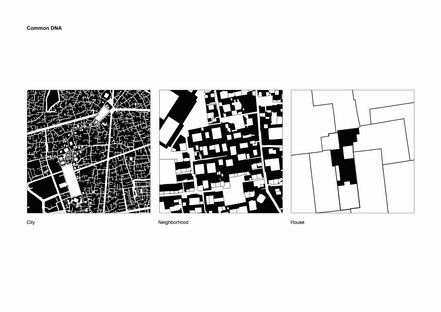

One of the main accusations that they level at the urban planning systems in Isfahan is actually directed squarely at themselves. Having contributed, some twenty years prior, to designing the urban planning tools for the city’s historical centre, Mohammad Arab and Mina Moeineddini admit that it was a failed experiment which they now attribute to a short-sighted vision that saw the city as nothing more than a body formed by a collection of occupied spaces, empty spaces and the paths between them. Where were its inhabitants? Where were their lives, where could they come into contact with one another? The depopulation of historical centres, in stark contrast to what has always been the case in large European cities, for example, has resulted in the space being emptied out and, consequently, the alienation of the individual. This superficial definition of what an architecture is - in other words, with the focus on its image and façade - wholly overshadowed its innermost essence.

Isfahan’s urban fabric as it exists today is dense and rigid, the buildings a regular and rhythmic series like a row of ‘boxes’, all closed in on themselves. The model of the courtyard house, which is traditionally fairly widespread, has been cast aside here, giving way to a municipal model that features a front courtyard overlooked by the building, closed off from the others and with no communication on either side. A sense of figurative monotony that goes hand in hand with monotony of function and experience has very much taken over.

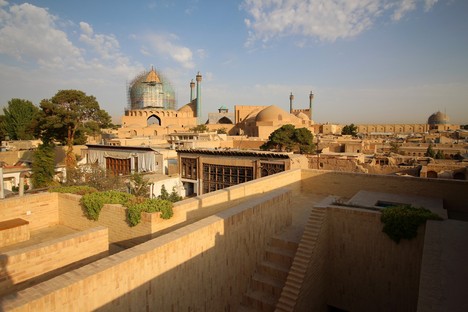

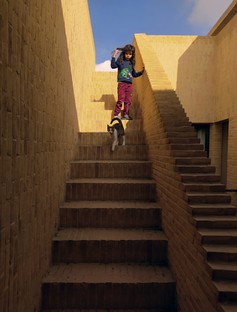

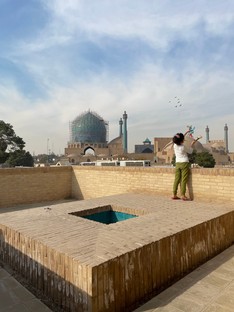

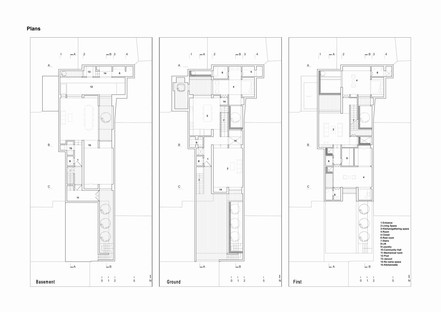

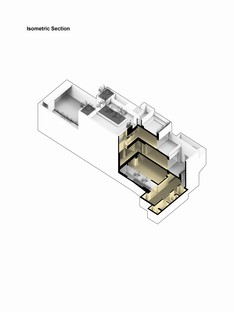

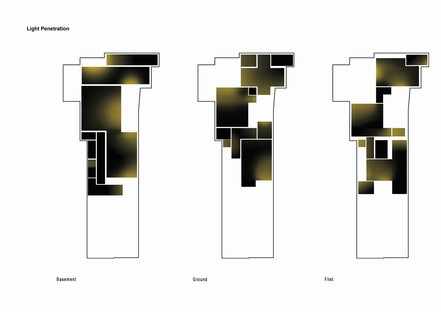

As such, the couple’s decision to buy a plot in the historical centre is not rooted in a desire to graft their home into a sort of open-air museum, but rather in a yearning to rediscover an atavistic quality of the space. The limited view, resulting from only a single outward-facing viewpoint, is counterbalanced by the rediscovery of the courtyard. Not one, not two, but three courtyards form the heart of Aban House’s layout, whilst the building’s upward development allows many of its rooms to be bathed in natural light from two directions. Each overlook provides access to a different living experience, which is fundamental for both individual and social growth. The third courtyard opens up towards the dome of the Abbasi Jameh Mosque, also establishing a particularly prestigious relationship between the top floor and the city.

Then, in order to establish the spatial distribution, the architects undertook an in-depth examination of all the various behaviours and circumstances that might occur in real life. Their conclusion did not result in their simply allocating the rooms for basic functions - eating, washing, sleeping and the like - but also shed light on the need to carve out spaces for unplanned functions. In this regard - the designers are keen to note - historical architecture is the most authoritative guide, as it created dysfunctional spaces to play host to unexpected events, dark areas alternated with light-filled ones, narrow passageways and vast open squares, resulting in the sense of dynamism that we as humans so deeply crave in our existence. Drawing on this example, the Aban House is made up of spaces earmarked for clear, well-defined functions, but it is also rich in hybrid spaces with an open-ended flavour of functionality. The existence of interstitial spaces offers a wealth of opportunities to simply relax, comfortably curl up with a book next to a space where their child can play, enjoy the solitude or drink in the view.

Brick is the material of choice here - not the industrial variety, but rather an earthy, handcrafted kind that is similar to the sort used in the construction of the Abbasi Mosque four hundred years ago, but equally the sort that distinguishes the surrounding houses, which date back to the first half of the 19th century. The decision to use these bricks, which are now almost exclusively the preserve of restoration works, represents a conscious effort to support the craft of small workshops - which are struggling to survive the competition presented by large factories - and re-establishes a link to the past. And with some success: it appears that following the construction of the Aban House, other clients have also encouraged the use of this handmade brick, helping to change people’s perceptions of this noble material. Of course, this may also be due to the fact that the use of clay brick, which have a lower thermal conductivity than industrial bricks, noticeably improves the feeling of comfort both indoors and outdoors. This is no mean feat in Isfahan, where the temperature range can be even higher than 20 degrees.

Mara Corradi

Architects: USE Studio https://use-studio.com/

Design team: Mohammad Arab, Mina Moeineddini

Associates: Elaheh Hajdaei,Nazila Rabiei, Arezoo Khosravi

Client: Arab Family

Location: Isfahan, Iran

Start of work: 2016

Completion of work: 2018

Gross useable floor space: 400 sqm

Lot size: 250 sqm

First prize of Memar Award 2018

Finalist of Brick Award 2022

Finalist Aga Khan award 2022

Photo credits: Ehsan Hajirasouliha, Mohammad Arab