20-06-2018

Interview with Francesco Marzullo

Francesco Marzullo,

Rome,

From the new trade fair district in Rho to the Casino Nobile di Villa Torlonia project, from the organisation of a two-year construction site with 2000 workers to restoration of a neoclassical jewel: who is Francesco Marzullo, really?

From the new trade fair district in Rho to the Casino Nobile di Villa Torlonia project, from the organisation of a two-year construction site with 2000 workers to restoration of a neoclassical jewel: who is Francesco Marzullo, really?I am the product of a 45-year career, of countless experiences in the field, of the passion and curiosity that have always characterised my work as an architect and engineer, with a desire to express everything I have learned over the years in my constructions, working hand in hand with Italy’s most prominent construction firms.

“Why an architect can finally talk to an engineer” is not a joke, it’s a philosophy, the common theme that has guided me ever since I started out in 1972 with Dr. Riccardo Morandi, to whom I owe my passion for the structural and construction side of my profession, and in my freelance work on all kinds of projects since 1989, working on hospitals, offices, police stations, homes, historic buildings, skyscrapers, stadiums and sports centres, the construction of which – for I have had the great fortune or the ability to build almost all the projects I have designed – required a lot of organisation and dedication, in view of their great complexity.

The work of my technical staff is based precisely on this, on dialogue, which is an essential condition for the success of a project and must be a deeply-rooted mindset not only within every specific field but in the way different professions interact and integrate, because everyone’s professional skills are essential in this line of work.

The design teams (architectural, structural, plant engineering, etc.) are totally independent, self-sufficient and capable, but they interface continually, sharing their know-how with the aim of identifying the best of the many possible solutions.

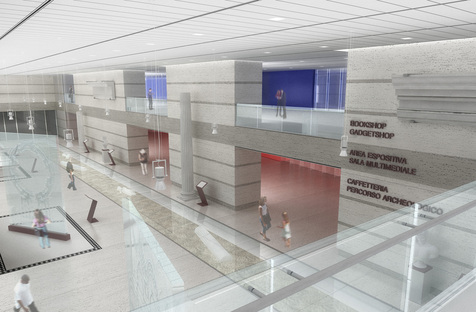

I have worked on projects in which the structural component was more complex and difficult than the architectural one, as in the case of the Regione Lombardia skyscraper in Milan. I have worked on restoration, reclamation, and historic consolidation projects, such as the Casino Nobile di Villa Torlonia in Rome. The metro station under the Imperial Forum in Rome was a project requiring yet another point of view, in which I adopted an absolutely “architectural” approach despite all the “structural” issues involved in a metro station project.

You teach in a master’s programme in which you talk about handling the complexity of the architect’s work today. Can you tell us how you address this issue with new graduates?

Dr. Riccardo Morandi used to say: “There is never one single solution, but many solutions,” and I add that we must be able to make a pragmatic choice among them.

Over the course of my 45 year career I have found myself addressing all kinds of projects, all very different and each with its own complexity, entity and nature: from the Fiera di Milano, a 630 million euro trade fair centre, or the Regione Lombardia offices, also in Milan, to Isernia Auditorium, which opened in 2012 with a concert by Maestro Uto Ughi.

I bring examples to my lectures in the Master’s programme of projects I have worked on that I would call “complex”, but I always tell my students that none of these projects really is complicated.

It us up to us to make a project more or less successful, more or less complex, more or less feasible.

The greatest difficulty may lie in identifying all the issues, formulating all the possible solutions and identifying the best one for solving the problem.

In our Master’s programmes we attempt to demonstrate how we approach a project, what is the mental process to follow, but also what our relationship with the construction site is like. After all, the aspiring physician studies in direct contact with the patient, and the aspiring lawyer undergoes an obligatory apprenticeship in a law office; and so the aspiring architect ought to be familiar with the construction and implementation of designs, from regulations to building materials, and from technologies to the construction site proper.

Your studio is based in Rome and has a lot of construction sites in the capital. How do you reconcile your role as a structural specialist with the constant need to reclaim Roman artefacts of inestimable value?

While work was underway on the construction of the Onco-Haematology Department at San Giovanni Hospital (a historic building in central Rome with heritage status, which we restored, adapted and consolidated, fitting it with cutting-edge medical facilities and equipment), we came across some priceless archaeological artefacts.

Or course the initial project then had to be changed and adapted to save a Roman villa dating back to the age of the Valeria family which was hidden below the building.

The work continued in partnership with the Superintendency for Archaeology, which took charge of the project and the plan, giving binding orders about when and where to act.

Our task was then to find a technologically functional way of completing the project which would comply with the Superintendency’s instructions and the need to protect the artefacts.

How do you go about designing a metro station under the Imperial Forum, the project you have been working on in recent months?

I have done a lot of research, obtained documentation and information, and sought to reconstruct the history of the place from every point of view.

What’s more, I’m firmly convinced that the true architect can be seen when he works within a system that puts restrictions on what he does; because in the absence of restrictions, you are not an architect but an artist.

Restrictions condition you, but in a “positive” way, because they allow you to make a choice and to find the best solution.

But having to address all these problems and all these complex and unusual situations has allowed me to come up with equally complex and unusual ideas.

The optimal solution, in the overall context, is the one that responds to and resolves the majority of the initial input, in agreement with the designer’s sensibility, of course.

What is your average project timeframe? Can you offer us some examples of different construction sites and different types of project?

The timeframe is determined by the client. Every project is a case in itself: we’ve had projects that lasted only a few months, and others that have taken years; we’ve had projects we began to design when the site became operative and finished designing at the same time as we finished building them.

This is why we prepare a “Design Plan” very precisely establishing everything that has to be produced, and a “Work Schedule” showing the time for issuing and implementing these plans, also in view of possible coordination with other planners.

Which is the most complex and interesting project you’ve been working on recently?

What attracts my curiosity the most recently is the study and application of all the new seismic regulations that are coming out right now and changing and updating the way we do structural calculations in Italy.

Moreover, we are overseeing a major competition in Milan, for the reclamation of a huge series of residential buildings to be transformed into an enormous shopping centre. This means adapting spaces in masonry buildings with major demolition work. It is a “work in progress” in which we believe we have identified particularly significant solutions that we hope to see implemented.

Mara Corradi