28-09-2022

Diana Kellogg Architects: Rajkumari Ratnavati Girls’ School, India

Diana Kellogg Architects,

With a degree from Columbia University and another from Williams College, New York architect Diana Kellogg was enjoying a brilliant career designing luxury homes and commercial interiors. That all changed when she happened to cross paths with Michael Daube, founder of CITTA, a non-profit organisation implementing development projects for poor communities with low literacy rates in marginal areas such as India and Nepal. When Daube asked Kellogg to design Rajkumari Ratnavati Girls’ School in Jaisalmer, Rajasthan, she agreed, and that was only the beginning!

The school is part of a wider-ranging, more ambitious project called GYAAN Centre, which also includes a performance space, a library and a cooperative centre in which local artisans teach women traditional weaving and embroidery.

The architect treats the three volumes as a single complex, standing beyond the sand dunes of Thar desert. Each space will have its own formal independence and identity, while at the same time forming a part of a single complex; simple sunshades make even the interstitial spaces usable.

The first of the three projects to be completed, the school now has more than 400 female students, from a community that lives below the poverty line, in which literacy among women is no more than 36%, reports the architect. To make sure the local people feel proud of the structure and therefore accept the change, the project dedicated time and resources to the construction of an environmentally advanced building. The entire structure is built of locally sourced stone, saving on use of energy for transportation and processing. Recycled ceramic tiles cover the roof, with solar panels using the strong sunshine to heat water. Rainwater is collected using traditional local techniques, with the addition of a system for recycling drain water.

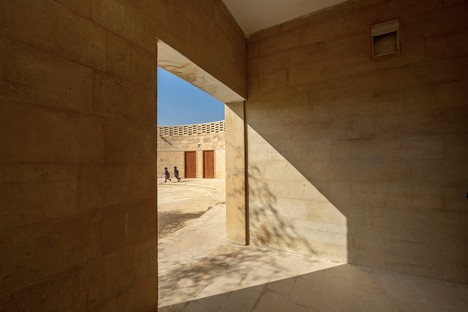

This progressive approach is harnessed in an form that makes the school a landmark, with its rigorous oval shape, rooftop belvedere with photovoltaic panels, wall decorations reinterpreting the traditional jali, and structure on a single level appearing to emerge out of the desert dunes. Entirely built of sandstone blocks carved by hand by local craftspeople, the building looks like part of an ancient landscape, blending in with the colours and shapes of the earth and the desert sands. Kellogg says that her design is inspired by the curved lines of the towers of the nearby fort of Jaisalmer, a walled city built in 1156 on Trikuta hill in the desert of Thar.

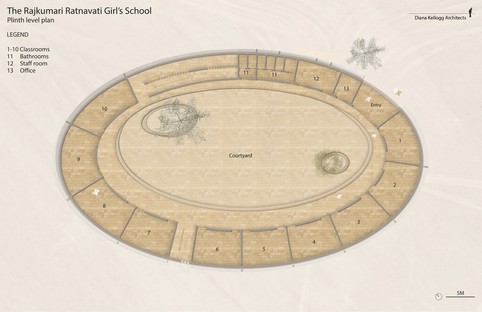

The floor plan is the outcome of a selection of essential spaces and careful budgeting. An elliptical courtyard, also lined with sandstone, leads to the classrooms, an office, and the staff room, set within the outer walls. The simple palisander furnishings and woven traditional chairs, like charpai, are all locally made. There are no decorations other than the natural differences in the veining of the stone and the poetic shadows cast by the jali. Kellogg fits them into the rows of tall windows in the classrooms, the railings of the rooftop belvedere and the walls of the monumental staircase. They used to form dense ornamentation on doors and windows, preventing people from looking into buildings from outside so that the women of the household could watch what was happening on the street without being seen; but here, jalis are designed with an open weave, maintaining ties with traditional architecture while taking forward: the decorative motif is no longer intended to conceal, but simply to provide shelter from the sunlight and heat.

The theme of protection also appears in other elements of the project, such as the floorplan: Kellogg says that the choice of an oval shape for the building turned out to be significant also because its sinuous lines suggest femininity, the womb, but also the way women work together. The closed shape, with no corners or openings, forms a private space, a place the girls can recognise as reserved for them alone, in a rural society still dominated by a masculine concept of living.

In this sense, it is significant that local artisans, including the girls’ fathers, were personally involved in the project: this became the key to overcoming the prejudice against the idea of a school for girls, making it into a community project.

“The two other structures that will be erected - the community centre and women’s cooperative - will also be oval in shape and together will become a symbol of infinity. This series of ellipses represents the idea that in a remote corner of India, women’s and girls’ issues can be amplified and attract attention on a global scale” concludes Diana Kellogg.

Mara Corradi

Architects: Diana Kellogg Architects https://www.dkarchitects.com/

Client: Citta India

Location: Jaisalmer, India

Gross useable floor space: 200 ft x 120 ft

Start of work: 2020

Completion: 2021

Photographer: Vinay Panjwani