08-09-2020

ONSTAGE: INTERVIEW WITH DONG GONG, VECTOR ARCHITECTS

Dong Gong is the famous founder of Vector Architects, one of the most authoritative and prestigious firms in China, where he returned after undergoing a very international experience. Several years spent in America allowed him to observe his country with the eyes of a native and also from a more Western perspective, certainly a more objective and global vision. Received Bachelor & Master of Architecture from Tsinghua University, followed by a diploma and a second Master at University of Illinois, with an exchange at Technical University of Munich, he did professional training in Chicago and then in New York at Richard Meier’s and Steven Holl’s offices. Bestowed several Awards of Excellence along his studies, he continued pursuing, both academically and professionally, an extremely brilliant career, with prestigious rewards at local and international level. Vector Architects since 2008, when they began their practice, have realized projects of great elegance and refinement, that have received great global acclaim.

Dong Gong is the famous founder of Vector Architects, one of the most authoritative and prestigious firms in China, where he returned after undergoing a very international experience. Several years spent in America allowed him to observe his country with the eyes of a native and also from a more Western perspective, certainly a more objective and global vision. Received Bachelor & Master of Architecture from Tsinghua University, followed by a diploma and a second Master at University of Illinois, with an exchange at Technical University of Munich, he did professional training in Chicago and then in New York at Richard Meier’s and Steven Holl’s offices. Bestowed several Awards of Excellence along his studies, he continued pursuing, both academically and professionally, an extremely brilliant career, with prestigious rewards at local and international level. Vector Architects since 2008, when they began their practice, have realized projects of great elegance and refinement, that have received great global acclaim.Site, Light, and Making are the main issues on which the young team focus their interventions. Architecture has its roots in the context that makes it something not empirical or abstract but real. The architect’s mission, according to their words, is to play a well-defined role: to explore and decipher the energies of a site, both natural and urban, studying its landscape, its inhabitants, their attitudes, traditions and subsequently, like a good orchestra conductor, direct these energies in order to forge unique perceptions and ways of life. He might be able, as on another occasion they poetically declared, to stir the still water of a surface, causing concentric waves that reach the heart of those in the proximity. These are the principles that allow a respectful approach to an environment to be protected, both as natural and as ruined remains, fragments of memories almost disappeared, traces that must be helped to tell again a story that could still speak to us of a past, which, part of our cultural and biological heritage, must make us understand how to move forward and continue our history. Globalization has fueled the spread of an inappropriate, I could say conventional way of looking at the identities that distinguish different realities and Dong Gong would like to incentivate and support more honest and authentic types of approach, which contribute to a good, true architecture.

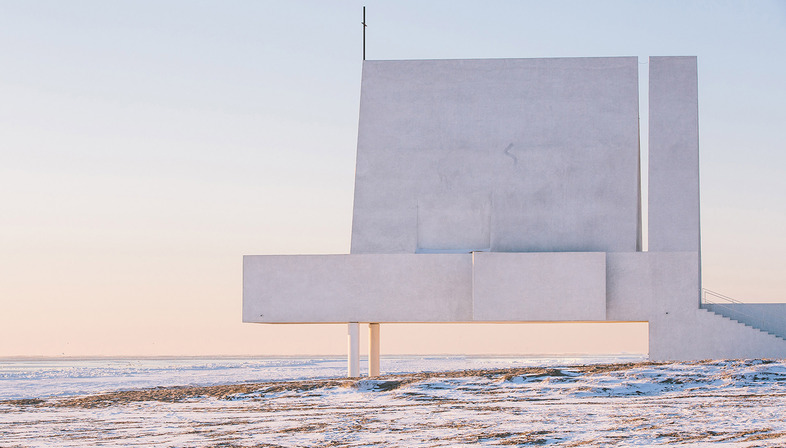

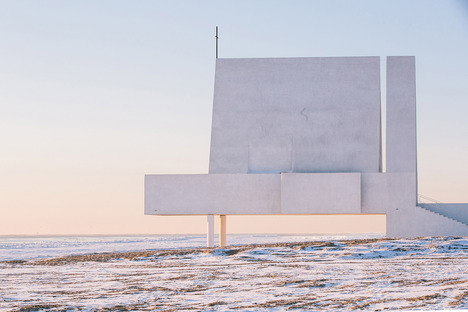

The term that best identifies his attitude of relating to regeneration and adaptive reuse’s projects is perhaps 'respect', and, although one of his major concerns is to maintain an attentive, reverent behaviour to the pre-existing and the existing, the artistic aspects that this profession implies are not neglected. Those who practice it have the same duties towards society as the artist: to guarantee a work that has an intent and a social educational value, without giving up an important aesthetic expression. According to these principles solos were born that release notes of high lyricism, in absolutely deserted contexts such as Seashore Chapel, the small church that makes one think of a wreck in the precarious condition of being again swept away by the current in the ocean. With its pointed roof, all stretched out in the apparent effort to reach a superior dimension, it symbolizes a longing between two immensities towards infinity, a gesture of invitation to reflect, or rather to meditate on the existence. In a similar situation but without pretending to let mystical accents emerge, we can admire the linear silhouette of the Seashore Library, opening up to the ocean with a different satisfying and relaxing sight. The materials chosen for its realization, gray concrete and wood in a rather dusty shade, seem not to aspire to find a special visibility under the sun, like the white walls of the small religious sign reverberating under the zenith light, but look for continuity with the sand, over which the elongated section of the building extends. The light in the first design example is calibrated and rationalized with extreme attention for the interior, that has to convey a sense of contemplation and silence, used instead in a different way for the outdoors, where purposely it want to emphasize the smallness of the point in a reality that goes beyond all physical limits and boundaries. For the cultural and recreational structure, on the other hand, the attempt is to underline the sense of welcome, making a scenographic use of the light, to enhance the strong appeal.

In Dong Gong's projects, both natural and artificial light are of crucial importance, creating different atmospheric moods, helping to better identify characteristics and peculiarities. Much of his production stems from an idea of architecture as an inseparable activity from an existence not always rationally accessible. Not being able to find answers that satisfy existential doubts, we must accept a certain 'ambiguity', indeterminacy caused by 'imprecise feelings’, alternating inside ourselves. Are especially the contexts in which old and new must find a trait d’union, where the backdrop is represented by a nature almost intimidating for its primordial force and suggestiveness, which develop somewhat rarefied atmospheres, which adapt to this state of conflict in search of harmony with infinity. It is the diaphanous seductive and very intriguing aura, result of 'paradoxical opposites' , that we can breathe and is dominating Alila Yanghshuo Hotel complex.

1 – What represented for your works your upbringing in China and practicing for several years in different international environments? Have both the experiences affected your design principles?

I am sure that your experience in life will affect your vision and the way you look at the world. I studied in China for my bachelor’s and master’s degree, then I went out to the United States for a second master’s, and practiced there for over seven to eight years. I believe the most effective thing is not necessary about architecture, or how much you trained in professional world or in a western system, even if it could be part of it, but rather the way you interpret the world and the life itself. You know the dimension as a Chinese, but you know it based on your experience, and how far different in another part of the world it can take on your life. That is the most crucial influence for me and that will definitely influence my value of architecture. I am not necessarily a literal or literally traditional China focused architect, as our previous generation like, Wang Shu, or someone similar.

2 – Have elements of your childhood influenced your deep connection with vernacular and shaped your passionate dedication in approaching and readapting traces of the past ?

Well, must be. It doesn't really depend if you accept or deny this kind of influence, it is already part of you. If I look back at these 40 years of my life experience, it was a very unique period of time for China. I was born in 1972 which was still under the Cultural Revolution, a very ideological circumstance of this modern China, and around the 1980s China started to open its doors to the outside world. In 1990, this type of commercialism, consumerism, started to take over the entire direction of the Chinese market and culture becoming the driving factor. These 40 years have been quite dramatic for how the nation transformed and transited throughout modern history. I believe that it is something belonging to vernacular. When we talk about vernacular, it is not really about physical, historical, traditional, material-space, but instead, is about this kind of social transition linked to a specific and unique condition that builds up the whole picture of Chinese vernacular. I sometimes feel lucky to be right in these 40 years of time, to witness this Chinese transformation process, it is very challenging, as many new issues are taking place with a too fast dramatic urbanization that produces new problems in the facets of the society. I feel that it is even more interesting comparing such kind of vernacular condition to this particular kind of physical vernacular.

3 – I read a statement of yours, which is very interesting to me: “architecture is neither beginning nor the end. Instead, it is a medium to connect and reveal”, could you explain what you mean?

In this contemporary architecture field there are a lot of cases where people tend to describe architecture as an object or a form. As architects, you start a design process and eventually the whole building has been constructed, and your mission is accomplished. But for me, and this is due my personal experience, in some of our projects, the most interesting stories happened after the completion of the project, when you see the interaction between people and space. This makes me feel that architecture is not necessarily a physical object, but rather, it is the power to connect people with people, people with society, and people with nature. As I had mentioned in my recent lecture in Chicago, there is one point that is very important: such kind of power of connecting and linking things, should be based on the strength of authentic architecture. It is not about a political or ideological will, it is about the very genuine quality of design that can generate and stimulate connections between different parties. That is the very intriguing aspect of architecture, which I explore throughout my entire design process.

4 – In the previous article, connected with your interview, I mentioned you as a skilled ‘shape-shifter’, able to assign new performing roles to vernacular presences in respect of their aesthetics: do you recognize yourself in this definition?

This might be related to another very important role of architecture. I believe architecture is part of this evolutionary progress of humankind history of building and constructing. That is why each design has to carefully look into the past, and to engage with what has already happened, in terms of culture, geographical climate, and even so, this might not be enough. We have to inject the contemporary quality into such engagement. Each piece of architecture has to belong to today but still have connection to the past. I am very keen on how to find a correct balance with the vernacular or past condition; the way you react and interact has to represent anyways the quality of today: the life quality, the technical quality etc.

5 – Your approach to old landmarks is based on the search of a continuity that, without copying or overbearing the existing, lets perceive both, and read the different imprints belonging to different generational times. How are you able to create so harmonious and distinct coexistence?

This is a big issue in China now. In the past 50 years of China’s urbanization process, we have experienced a period of time when we didn’t really interpret the old traces as a valuable thing to be preserved or protected. The problem is that we demolished a lot of things, building new ones on top, and then the city gradually transformed into an alien context. We even changed the road system, the entire urban structures in a very short time, and people started losing their connection or identification with the place they lived, and that became a social issue. Reflecting on architecture, in today's practices we have to resist these certain unease transformations on our living context. We recently had five or six projects where we had the opportunities to relate the old with the new, protecting the traces of the past. We have to reveal where we are from, but is not only a literal protection of the past, we have to provide a new quality that represents the contemporary culture of the moment. It is really about this relationship between the old and new. In terms of techniques or tactics, there are many ways to approach these types of interventions, from materials, spaces, atmospheres, tonalities, etc. This is now a valuable effort in China, considering the general circumstance of the urbanization process.

6 – Do you share this idea that the most compelling and convincing plot of today storytellers consists in creating a synergic connection between people and building?

Yes of course, I think people are ultimately the very key part of architecture, but the most difficult is not a kind of theoretical term or terminology, but instead how you actually design and realize it in the architecture.

7 – Do you believe that an architect should be in awe of what in Chinese is called ‘Tian’: how is it possible to translate this term into European culture? Does a direct correlation between the two cultures exist? How did you approach the special uncontaminated context of Alila hotel?

In Chinese culture you can translate ‘Tian’ as nature, but it’s a lot more, it has somehow a layer of meaning that is the order of cosmos. It is not only about the physical landscape, context and sky. In China this is the ultimate respect of everyone’s cultural life and people worship ‘Tian'. It embraces a very powerful and mysterious order. Of course, the European culture might have come across similar interpretation, the Europeans might not call it ‘Tian’ but this kind of revelation of the order of the cosmos can be found, for example, in the Renaissance architecture, in the mathematical gold proportions, the harmony of the music. It is still a little different in China, it is not about a scientific part, it is something that lays in a mysterious region.

Well, in Alila, referring to ‘Tian’, probably the keyword is respect. It is really about believing in something beyond what you can touch, you can hear, you can feel. There is something powerful, even if it is not visual, beyond the human world, the cosmos. So when we tried to deal with Alila, there were two major factors throughout the entire design process, how we approach the new intervention in relation with the existing sugar mill and then, the artificial architecture in respect to the entire surrounding landscape that is spectacular, really dramatic. We worked a lot with the profile of the building, the tonality, the palette of the materials, and even in the masterplan layout: our concern was to find a respectful gesture for the old remains and the nature.

8– “Unfinished buildings have the charm of what might have been. Of what is not yet there. Of what might one day be there”, – Marc Auge’, ‘Le temps en rovine’: what do you think about this quote?

That is very poetic. It is like a painting, sometimes you see a masterpiece that is not finished in its evolution and for me this kind of processional trace of the artwork is like a section of an artistic creation. You can see layers of information, it is not closed yet as an open window, where you can glance at the process, the skeleton, the stratification of layers, of something when is being created. For me, it is similar to going into a construction site. It almost reminds me of visiting ruins of the past: these historical remains with their age and decay, dilapidated plaster and stones, nurture your own imagination. This is a very powerful statement.

9– Light embodies an important role in molding your spaces. Is this coming from your previous practice in Richard Meyer’s and Steven Holl’s firms?

Well, it has not been initiated by these two architects. I studied in the University of Illinois, my thesis supervisor, Henry Plummer was an expert in studying the relationship of natural light and architecture, however, he didn't really design, he was more theoretical. He gave me a substantial impact of my interpretation in the role of natural light.

Richard Meyer is a little bit different, of course he accentuates on light. For him it is the power to make some architectural phenomena visible, or even the architectural language. In some of Steven Holl’s buildings, the light becomes a kind of atmosphere, you walk into a space and you feel immersed in such quality of light, the light itself becomes an ambiance. In Richard, the light is always trying to depict the structure of the architecture or the space.

These two architects are different. But Steven might not be the best example of the second type of light that becomes atmosphere, maybe Louis Kahn or some projects of Peter Zumthor are more accurate examples where light itself is revelation, rather than light as a tool to reveal things.

Virginia Cucchi

Credits:

Vector Architects - http://www.vectorarchitects.com/en/

Seashore Chapel

Foto: ©Shi Zheng/ Aogvision and ©Chen Hao, Cortesia di Vector Architects

Seashore Library, Qinhuangdao

Foto: ©Su Shengliang and ©Xia Zhi, Cortesia di Vector Architects

Alila Yangshou Hotel, Yangshuo, Guilin, Guangxi, China

Foto: ©Su Shengliang and ©Chen Hao, Cortesia di Vector Architects