13-03-2020

Arbol: House in Akashi, Japan

Arbol,

Yasunori Shimomura,

Akashi Hyogo, Japan ,

Arbol designed a small single-family home for a couple with three children in the coastal town of Akashi, on Japan’s Honshu Island. Selected among emerging Japanese architectural studios in The Architectural Review’s Emerging Architecture Awards, Arbol has so far worked on small new homes on narrow lots in urban settings, a very common situation in Japan which leads to profound reflection on the concept of dwelling in the country.

Anticipated in their house in Nishimikuni, a neighbourhood in the metropolis of Osaka featuring the same building materials and layout on a single floor with patios, the design of the house in Akashi shares a number of the older house’s environmental features which are characteristic of houses in Japan: the small size of the lot on which it is built, which has practically the same surface area as the home itself, the urgent need to protect the clients’ privacy, and the search for the most efficient way of using indoor space, and the need for dialogue with the element of nature, in the Japanese sense of the term.

The project in Akashi is also located in an urban, industrial setting (the city is home to one of Kawasaki Heavy Industries’ factories) where new homes are being constructed in suburbs built up as the city has grown along the coast. The Japanese people’s relationship with nature, which often appears very close, is now considered by many a form of mediation between a past in which man’s coexistence with nature was the result of a rural lifestyle in close contact with the landscape and a present in which greenery is increasingly somewhere else, somewhere far away from the utilitarian life of work and the metropolis. This theory of the distance the Japanese have assumed from nature is put forward in “A Japanese anthology. Cutting-edge architecture”, in which Leone Spita mentions examples such as the idea, subsequently implemented, of building a concrete wall 12 metres high and almost 400 km long along the coast of the region of Tohoku, struck by the devastating tsunami of 11 March 2011. The idea of building such an impenetrable barrier between people and the sea, inconceivable for westerners, was favourably received by many people in Japan, and the government actually built the wall.

To the Japanese people, the need to keep nature at a distance from their everyday lives, no matter how much they love it, has led contemporary architecture to imagine a form of nature that is no longer wild, but anthropised, regulated and confined on the basis of the laws of artificial dwelling which always prevail over it.

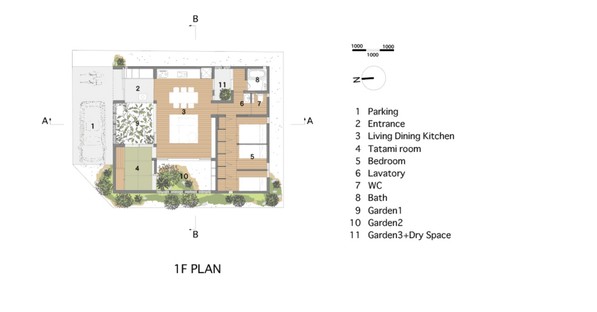

The houses designed by Arbol, first in Nishimikuni and then in Akashi, must be interpreted in light of this, rather than as an abandonment to nature, or an attempt to allow nature to prevail over the city. Comparison of the size of the lot, 170 metre square, and the indoor floor surface, which is about half of this, is however an indicator of the architects’ effort to save some land for greenery, as, to cite Leone Spita once again, “for the Japanese, even a tiny strip of land surrounding the home is sufficient to raise the inhabitant’s spirits”. This effort is made not for a multi-storey building, but for a home on a single level, and therefore with limited living space, in which there has obviously been attentive reflection on the layout of indoor space leading, for example, to minimisation of the number of rooms. The spaces, which are never shut off to the view but reciprocally permeable, are divided according to the essential functions of living, clearly in agreement with the clients: three sectors have been identified, for sleeping and eating and for the tatami room, an undefined space complementary to the other two in which to read or drink tea on the tatami mat, a traditional Japanese flooring material made of modular panels of wood and woven straw.

In these three areas, combined to form a basic rectangular floor plan reflecting the shape of the lot, indoor and outdoor spaces have been created, one destined for human occupants and the other for plant life, one made of soil or rocks and the other covered with flooring. This makes the Akashi house a successful synthesis of contrasts. The fact that all the “human” spaces are made of or covered with wood gives the house an even more natural feeling, though it is still a representation of nature, however skilfully designed and built. The architects of Arbol emphasise the care the company took in choosing the right types of wood (from cedar, to Japanese cypress and European spruce) for the floor, walls, pillars and beams, which are not normally considered so important in the house as a whole.

The alternation of indoor spaces with patios and the decision to open up many of the partition walls with glass ensures that the natural elements reconstructed in the home are visible from any point inside the house.

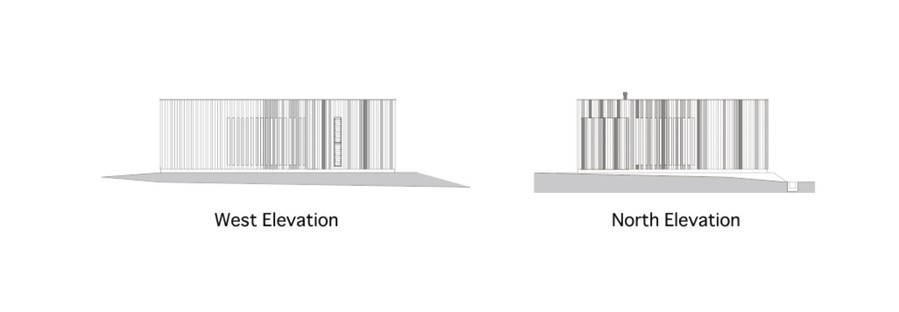

On the other hand, the city, the neighbourhood and other people are shut outside, beyond the compact wall that encloses all this nature in a sort of box, a minimal parallelepiped made of cedar wood, with openings only at the entrance patio, primarily decorative slits offering a glimpse of life inside. As in many of the contemporary Japanese architectural projects we have discussed over the years, this near-total shutting off of the home from society is one of the solutions most commonly adopted, preferring to reconstruct an entirely private life within the home that incorporates nature. But in the house in Akashi, this separation admits an opening in the roof, thanks to the patios: as the building is on a single level, the inner courtyards contain and bring into the house the path of the sun and the passage of time, daily atmospheric phenomena and natural ventilation. Nature continues to live its life and flow in sheltered little rooms, even when the city outside denies them.

Mara Corradi

Basic design & execution management: Arbol

Detail design: Arbol + Hasuike

Location: Akashi Hyogo, Japan

Structure: cedar wood

Outer wall: Galvalume

Inner floor: cedar wood

Wall: Plaster coating

Top: Plaster coating

Period: January 2018 - July 2018

Builder: Sasahara Corporation

Gardens: Oginotoshiya landscape

Coordinate: Arbol

Lighting design: Parco space systems

Furniture: SITATE Bandai Mfg.

site area: 172.81 sqm

total floor: 81.07 sqm

Photos by: © Yasunori Shimomura