Already decades ago, statements were made that were not only not heard but often also snubbed. Jane Jacobs, for example, had declared that a city dies if it does not embrace diversity, a quality that at the moment seems to be greatly re-evaluated and reconsidered as an indispensable ingredient for a society, that in the multiplicity of its most varied resources, can find the key to affirm it own success. Unfortunately, this diversity, which is rightly celebrated as an indispensable enrichment, is not as much encouraged in the urban reality. “To understand cities, we have to deal outright with combinations or mixtures of uses, not separate uses, as the essential phenomena", rightly warns Jacobs, who would like to make it clear that the urban ecosystem is formed by complexity and heterogeneity, and “the architectural order desired by the planners will never replace that social order, made up of small, informal and unexpected human activities, which is the basis of the urban vitality”. In a district it is crucial that its components perform as many basic functions as possible, housing, commercial activities, businesses, services and many small blocks, constituting its essence. New and old buildings must alternate and a good population density must favour intergenerational and multicultural exchanges. An excessive simplification destroys that texture gradually weaved by small supports, so called sub-economies, that progressively add in proximity. The neighborhood should be taken as a unit of reference, a small-scale model of a more complex planning, a microcosm of needs to be projected on a larger scale. But what is unfortunately happening, as warns us for some time now the famous urbanist and critic, Joseph Rykwert, recipient of the RIBA Royal Gold Medal and prolific writer of books on the rise and evolution of cities:“what's happening is that - this is common knowledge - the price of property in city centres is making it impossible, particularly in the big cities, for any kind of social mix to take place. It's castrating the whole notion of city life”.

As cities develop, expanding at a faster rate, urban policy makers seem unable to provide new services, public houses or urban spaces, upgrade old facilities, without affecting dramatically the poorest and most vulnerable citizens, making impossible the healthy diversity that allows cities to thrive. Even Michael Sorkin, architect and critic, absolutely agrees on the need to preserve the quarter as a synthesis of socio-economic experiences fed with vivacious exuberance by the community and the proximity . If you imagine it, he tells us, equipped with all those services that can make it completely autonomous, “a place in which all the necessities of everyday life can be found by walking five or ten minutes, then you begin to re-conceptualize the city in a much different way.” And he continues by listing the advantages: "Certainly one is the convenience; one a series of environmental benefits, but another really important is the social mix”. And he also adds: “If everybody who works in the neighborhood lives in the neighborhood, then that means there has to be housing that's available to the barista, and the banker, and the urban farmer, and the artist and whoever else… a neighborhood that, in the nature of its functionality, also incorporates the hospitality to everybody in the city”.

A compelling logic, a very convincing reasoning, and a perspective that sounds captivating, except that, as Sorkin himself points out, accessibility has essentially turned into a problem of ethnic and economic segregation. And if we think that within 30 years, according to forecasts, 70% of the world's population will live in urban city, finding homes for this new and booming population will be a particularly challenging demand. What in the past had been considered a right, it appears from decades deeply threatened and today, speaking in increasingly generalized geographical terms, we could say that it has acquired the opposite characteristics of privilege. Social problems and poverty are generally confined to the edge of the city. The way to stem this ever-widening rift does not promise easy goals and should find urban policies, perhaps a utopia, willing to contain land prices within more reasonable limits, controlling private building speculation and supporting mixed residential developments, including a portion of reserved units at a fairer price.

Peter Buchanam in his extensive 'The Big Rethink', after long considerations and reflections dedicated to urban design, decides to abandon his discussion, limited to buildings considered without an environmental and human context, as they cannot help a true sustainability. When the architect is designing, Buchanam suggests that he should take into account the perspective of a sufficiently tempting lifestyle “replacing the alienating environment bequeathed by modernity, to which we could not relate and that impeded our relationships with others and ourselves,” and this alternative, he argues, can only be reserved by “the neighbourhood in which we once again feel at home in the world” . And he describes this small universe in miniature, the only environment capable of fulfilling a satisfying aspiration for life, as “extraordinarily rich of experiences − in which its residents grow up, mature and age in the embrace of community and nature”. He concludes by proposing a new type of prototype neighborhood that could really express a more resonant connection with all aspects of the human condition, suggesting a genuinely enriching approach to individual and community life.

During the podcast I am conducting, I had several guests who addressed the housing topic in the perspective of a renewal of urban fabric and collective living closely interacting together. Alison Brooks is precisely one of these architects who has always considered not only a duty but a personal ambition to commit her energy in improving the great problems represented by housing sector and public spaces. Left Canada shortly after graduating and, landing in London, within ten years, she set up her own studio, becoming soon an authoritative voice of her generation, and never renouncing to dedicate a significant part of her time to ‘heal’, for using her words, the conditions of housing and public space after a long period of severe neglect under Thatcher in 1980s. Alison's great aspiration was to help rethink precarious situations with new meanings and gradually her award-winning projects have introduced everything that she summarizes with an oxymoron, ‘Magical Realism'. As an extremely pragmatic woman, she understands that, due to a certain lifestyle and work necessities that have progressively changed, the times no longer adapt to urban forms and typologies marked by rigid and schematic divisions but rather are required more appropriate paradigms based on a greater hybridization of uses and contents, offering narratives that, by exploring more efficient solutions and adequate values, could satisfy real needs and nourish human potentialities, utilizing architecture as a tool that could also make people dream.

She rejects the idea that economic housing affordability could be to the detriment of a heterogeneity of residents and, firm supporter of socially mixed neighborhoods, to avoid rigid zoning or segregation, she appeals to her profession as an instrument of social justice, inclusion and coexistence. Considering housing inseparable from neighborhood life and the most important type of social architecture that "frames the collective space of our civic commons and negotiates the relationship between private and collective", she dedicates passionate concern for "delivering along with new buildings a sense of civic pride and social rejuvenation”. She strives to develop authentic and responsive alternatives for both buildings and the urban fabric, each with a distinct identity and a positive impact on the urban realm, realizing many housing schemes that provide a balance of public spaces and mixed-income, conferring that added value that architects are often able to offer.

This year at the Venice Biennale, she presented 'Home Ground', a new stage in this open-ended discourse, inviting to a reflection on the 21st century housing "as a place where people work, create and communicate". The beautiful and scenographic installation captures us with magnetic seduction for its strong emotional impact, caused by the contrast between materiality and intangibility, full and void, emphasized by a particularly warm and atmospheric light. Sixteen models in natural wood reproducing housing plans designed and proposed over the years by the studio have been arranged on the extensive surface of a table, surmounted by the corresponding living volumes suspended in mid-air and almost evanescent due to the milky translucent effect of the material. The game of this juxtaposition was intended to invite the public, once focused the attention on the contingencies and complexities that have led to shape each project, to share new conversations on the nature and destination of the ‘ground floor’ communal spaces, "as both thresholds to the private realm of the home and gathering spaces, where new communities can form". The goal was, of course, not to present an "ideal city" but to accompany reflections and to rethink a new role for residential housing architecture.

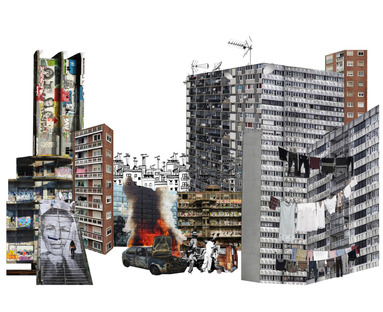

Another of my recent guests was Benedetta Tagliabue, a woman with a strong empathic and communicative personality, a warm Italian-Spanish mix, I would say, that she conveys with a lot of energy through her realizations that far from rigidity, embrace a sinuous organicity, engaging people and encouraging inclusiveness. She is the author of an interesting community project that is taking shape in the suburb of Paris, a complex and difficult area that has seen unrest in the past, mainly inhabited by a multi-ethnic population of immigrants. A context stigmatized by marginalization and poverty that needed to be helped to forget the state of decay and squalor to which it has been condemned for years. Benedetta is not new to seam lacerations that break urban fabric’s continuity and cause discomfort all around. It is very clear, as she explains in an interview, what her concept of regenerative intervention is: “When in any city in the world you detect obstacles, barriers and therefore hostile places, you tend to change your opinion and you are led to turn it into negative. To make places lose hostility you need to have generosity, a deep vision projected over time, dense of exchanges and openness ".

Architecture feeds on the past, on the stratification of life experiences and it is not by making a clean sweep and denying a continuity that we safeguard our culture and recover parts of a fabric that have been slightly torn. There are many examples in her portfolio that show us how a careful observation and a sincere will to mend, bringing dormant voices to be heard again, have produced highly effective results, in the name of respect and authenticity. And the reference to the Santa Caterina Market in Barcelona sounds almost peremptory, a situation closely linked to an ancient district, that was a mosaic of diversity and needed to recover the atmosphere of liveliness that had always distinguished it. A mutual hybridization of old and new has once again allowed that lifeblood to flow in this 'important vein of transition in the neighborhood'. “A place full of life, a historic place full of positive elements that had fallen into decay and, with a wonderful experiment of urban transformation, has regained value", proclaims the creator with pride.

In the Plateau Central masterplan, in Clichy-Montfermeil, Benedetta has intervened with the usual delicate touch and positivity of transforming greyness into vibrancy, a lived-in space without a sense of belonging into a dynamic and engaging environment. During both of these last editions of the Venice Architecture Biennale she presented two installations with reference to precise phases of this project. In the titles assigned to both the exhibitions we read themes dear to her and frequently recurring in her works: the 'market' as a moment of meeting, exchange and easy socialization and the ‘interweaving that, inevitably evoking her famous wicker pavilion, alludes to the willingness of encouraging connections and interactions. It is the 'human measure' that interests her and she intends to recreate, the one that Jane Jacobs opposes to the calculated schematic orthodoxy of certain traditional urban planning models, that doesn’t appreciate and allow those 'walks' in the neighborhood, as she loved to do, and that daily life she was used to lead, dropping children to school, going shopping and spending time with neighbors,

‘Weaving Architecture' refers to a long roof, a structure of thousands of American red oak, steel, synthetic fibers and carbon minerals, basalt and glass modules interwoven together, to accompany people from the new subway station exit to the plaza. The concept of weaving does not remain a symbol but animates the entire program of the site, tangibly imprinting this rebirth based on participation and strong social values.

'Living inside a Market - Outside space is also Home' identifies the function that two housing blocks, 'Centr'Halles', will perform in close connection with a large porous and colorful market that, occupying the entire ground floor between the buildings, will energize the environment. The dynamic and lively, generous and attractive informal space plays a catalyzing role. It becomes a focal point for the community and weaves a fabric made up of relationships and opportunities, voices and stories that will alternate every day and enrich this neighborhood. The boundaries between buildings and voids, private and public areas fade according to the aspiration unifying Benedetta's works: to find continuity around them and start a dialogue that will break barriers. A sense of belonging is growing, making everyone feel at home even outside of their own housing unit. The roofs of apartments too, conceived as green areas, will knit community bonds, offering the opportunity to cultivate common edible vegetable gardens and urban farms.

Virginia Cucchi

Credits:

cover, 01-07: Alison Brooks. 'Homeground' installation. Venice Architecture Biennale 2021. Courtesy of Alison Brooks Architects, ABA. https://www.alisonbrooksarchitects.com/

08-11: Benedetta Tagliabue, ''Living inside a Market - Outside space is also Home' installation. Venice Architecture Biennale 2021. Courtesy of Benedetta Tagliabue– Miralles Tagliabue EMBT, photo of Marzia Faranda. http://www.mirallestagliabue.com/

12-22: Benedetta Tagliabue, project of Clichy-Montfermeil. Venice Architecture Biennale 2021. Courtesy of Benedetta Tagliabue– Miralles Tagliabue EMBT. http://www.mirallestagliabue.com/