29-09-2022

Where beauty lives: the ‘piano nobile’ or main floor of Fondazione Rovati

Design, Antonella Galli, Fondazione Luigi Rovati,

In the beginning it was a sumptuous home: the residence of the Prince of Piombino, built in 1871 in Corso Venezia, showcase of the nobility of Milan. Not many years later, in 1888, the Bocconi family, an emblem of the new enterprising middle class, took over the home; in 1958, in the midst of Italy’s economic and cultural boom years, it was purchased by the Rizzoli family. The history of the palace at number 52 Corso Venezia comes down to us via the Rovati family, who purchased it from the Rizzolis in 2015 to provide a home for Fondazione Luigi Rovati, a cultural centre and museum that finally opened to the public in September. The history of the building explains why the Rovati family did not treat the palace a mere container, however spectacular, for their foundation’s cultural events, but as a living part of them. The building is itself an all-encompassing total work of art, in which spaces that were originally functional now provide a home for beauty to dwell in. In this spirit, the “piano nobile” or main floor, open to visitors along with the new underground museum, now houses the collections of the Rovati family, as well as artworks on loan and temporary installations, in close dialogue with the décor of the building: the floors, woodwork, fireplaces, mirrors, windows, niches, shelving and corridors.

Mario Cucinella is the architect who planned the overall restoration of the palace and its new installations. The heart of the Etruscan collection is kept underground, with contemporary art on the building’s main floor. In these halls the boundary between ancient and modern, between past and present, is very labile; there is a constant flow built around assonances of colour, shape, and cross-references among artworks, spaces and objects. “The various different components of the installation estalish a narrative continuum in a dialogue of contrasts and similarities between the ancient and the contemporary,” explains Giovanna Forlanelli, daughter-in-law of the late Luigi Rovati and Chair of the foundation, “providing specific stimuli for visitors, who enjoy the architectural spaces themselves as an emotional experience, in addition to the artefacts and artworks on display. The architecture, with its continually changing forms, lights and colours, is not just a container, but a part of the museum itself”.

Woodwork and textiles, mirrors and fireplaces have been philologically restored to their original condition, while respecting the interior design project by Filippo Perego in the sixties. Each room has its own leitmotif: the room with greenish-blue woodwork and display cases full of Etruscan bucchero ceramics is dominated by Andy Warhol’s ‘The Etruscan Scene: Female Ritual Dance’ (1985), in which the artist reproduces the figures of the dancers painted on the walls of the Lioness Tomb in Tarquinia against a pale green background. In the Hall of Weaponry, the thorny branches of a rose plant sculpted in wood by designer and artist Marianna Kennedy intertwine on the mirror over the mantlepiece. Francesco Simeti created tapestries for the central corridor featuring highly detailed imaginary figures, multiplied and reflected in the eighteenth-century mirrors. The big hall with fuchsia woodwork features the light-hearted fantasy paintings of Luigi Ontani, in a silent dialogue with ancient statues of various different origins in the centre of the room, on a curved table designed by Cucinella himself. The Baroque entrance hall features a Lanterne à quatre lumières by sculptor and designer Diego Giacometti, brother to Alberto.

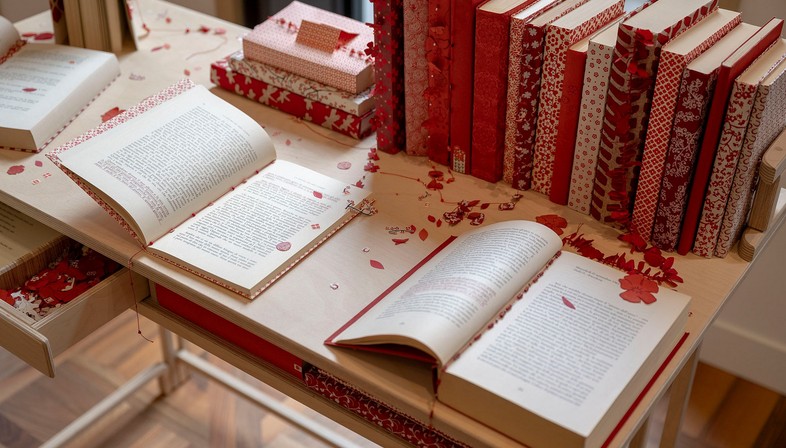

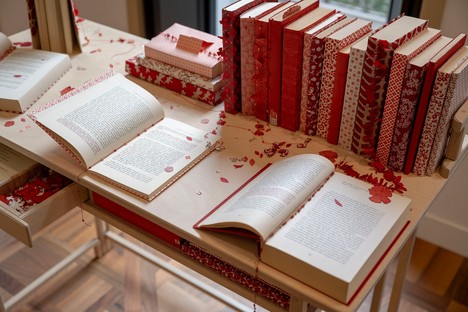

Lastly, the White Space is a hall with white walls and a classic parquet floor for housing temporary exhibitions. Until the end of November it will be showcasing ‘La vulnerabilità delle cose preziose’ (“The vulnerability of precious things”), an installation featuring two works by Sabrina Mezzaqui. In the centre of the hall, a small desk forms the heart of ‘Autobiografia del rosso’ (“Autobiography of red”), a work consisting of 33 books (diaries, memoirs and autobiographies) which the artist has selected from her own library, bound and decorated with red paper. The books lie open, with passages underlined in red: reflections on life that the artist shares with visitors. Testifying to how beauty can be found in everyday things, in the most ordinary of objects, such as books lying on a table in an ordinary room.

Antonella Galli

Captions and photo credits

All images courtesy of Fondazione Luigi Rovati.

Photo credits Giovanni De Sandre, apart from images 06 and 15

Fondazione Luigi Rovati, Milan; installation on the main floor.

01 and 14 Warhol Room

02, 10 and 11 Ontani Room

03 Kennedy Room

04 Giovanna Forlanelli, Chair of Fondazione Luigi Rovati, in the Ontani Room

05 Entrance to the main floor with the suspension lamp by Diego Giacometti

06 and 15 White Space, Sabrina Mezzaqui, Autobiografia del rosso (“Autobiography of red”)

07-09 Simeti Gallery

12 and 13 Paolini Room

16 and 17 White Space, Sabrina Mezzaqui, Groviglio