Prime Minister Nehru appointed Le Corbusier to plan the a new city that would become a symbol of India’s freedom, released from the traditions of the past, definitively marking the end of the country’s economic and cultural subjugation.

Prime Minister Nehru appointed Le Corbusier to plan the a new city that would become a symbol of India’s freedom, released from the traditions of the past, definitively marking the end of the country’s economic and cultural subjugation.The city still has a good reputation today for the quality of its residential architecture and public facilities, including hospitals, a university campus, museums, parks, and green areas for leisure and sports. The entire Capitol Complex designed by Le Corbusier was declared a Unesco World Heritage Site in 2016.

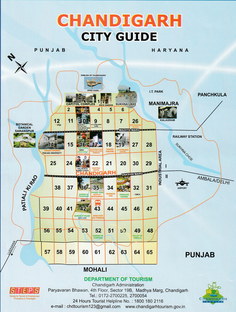

The Siwalik sub-Himalayan mountain chain provides an extraordinary backdrop for landscape architecture of essential importance in Le Corbusier’s urban plan for the city. The city is based on a grid with a square mesh, inspired by the regularity of farmers’ fields, while the city’s sectors are joined by roads classified into seven categories on the basis of the “7Vs” system, classifying roads by speed, from highways connecting Chandigarh with other cities to pedestrian paths.

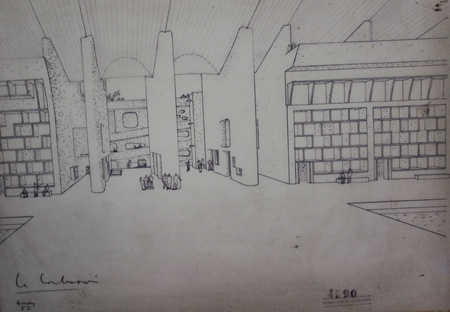

The Capitol area in Le Corbusier’s ideal city was intended to house political power, not to be a business district. The area stands out for its big separate buildings, with a “poetic reaction” to one another, the axes of which give structure to the outdoor spaces. A 700 metre long rectangle formed of two identical 350 metre squares, which are in turn divided into four along each side, accessed from the city centre via a bridge over a canal, a reference to water as a symbol of purification in Indian tradition.

High Court - 1951/1955

The big “Parasol and Umbrella” building contains the Supreme Court, on three levels, and a row of eight courtrooms, on two levels. The offices are accessed via a ramp in the shade of the arcade. The colourful concrete volumes with round holes in the pillars are visible; the courtrooms are sheltered from the sunlight by sunbreaks like those that may be found in the houses of Chandigarh, made out of brick and concrete frames painted white.

Secretariat - 1951/1958

A long parallelepiped that looks like a skyscraper lying down contains an “industrious mass of cells”. The offices are accessed via two ramps linking the pillars to the roof, on which an architectural landscape is recreated yet again. The offices are located in a continuous series of five blocks with a sunbreak for shelter, while the rhythm of the façades is regulated by the Modulor, so that the façade itself becomes a wall of images, broken up and laid out.

Palace of the Assembly - 1951/1962

The Palace of the Assembly has three main components: the arcade across from the Capitol and the two assembly halls with different roofs. The hyperboloid of rotation sheltering the Lower Chamber is a result of observation of the cooling towers of Ahmedabad, while the access tower and the pyramid covering the Upper Chamber, two unusual cones, suggest that a sort of solar ritual is taking place on the roof. The main access is through a big arcade before the plaza, which was in the past reflected in a big pool of water.

The main entrance is closed off by an enamelled steel door on which Le Corbusier depicts animal motifs and his modulor man. Lastly, the hypostyle staircase with its forest of columns adds rhythm to the stairs and ramps.

Travel notes

Visitors come to Chandigarh via the foot, so to speak, in the sense that Le Corbusier’s ideal construction is entered from below, from the city’s southern outskirts, which represent the feet of a plan conceived like a human body. If we are fortunate enough to survive the city’s chaotic traffic, we travel along the tree-lined avenues and traffic circles that are the city’s lungs, around the shopping centre that is the equivalent of its stomach, to the big government buildings, the "brain" of this anthropomorphic city, with its grey Capitol containing the Secretariat, the Legislative Assembly and the Supreme Court. These three concrete giants, flaking in the forty-degree heat of Punjab–Haryana, represent the symbolic Chandigarh. And this is where visitors can appreciate the paradox of a situation that has only become even more complicated after fifty years of independence, and ask themselves: after all these years, how bold does Le Corbusier’s utopian design appear to be? In some ways, nothing seems to have happened, and the city’s modern structure seems to have influenced its lifestyle. The population of Chandigarh has of course grown in fifty years. Despite all the planning and emphasis on “a full and harmonious life”, the majority of the city’s inhabitants live in precarious, illegal buildings, and traffic has doubled over the past few years, so that the big avenues so intelligently designed by Le Corbusier are just as chaotic as the streets of any other Indian city. And the situation has become even more complicated politically: Chandigarh has become the capital of two states, and Le Corbusier’s Capitol has been subjected to a grotesque division of space, allocating 60 percent to the Punjab and 40 percent to Haryana, which share the Secretariat and the Supreme Court. The mood in the city today is divided. Some say that that "the planning of Chandigarh is wonderful, but the architecture is a series of monstrosities," while others still venerate Le Corbusier as an architect, while maintaining that "Chandigarh proves he was a terrible social theoretician". Some think the city represents a bold experiment that was on the whole successful, while others denounce the clash of cultures between urban planning and the colourful, chaotic, "natural" character of Indian cities, and others yet remind us that quality of life is better in Chandigarh than anywhere else in India thanks to this form of city planning and all its rules. Perhaps it would be a good idea to talk to the students sitting on the lawns of the Punjab University to find out whether Le Corbusier and his utopian city imposed a different model of the “market” from outside the country on India.

It is impossible to stop the natural growth of cities, and in fact India’s centuries-old markets have been spontaneously recreated, the verandas missing from the city’s social housing have been converted into garages, new buildings of questionable legality are springing up all over, and taxis and scooters driven by turbaned Sikhs scoot about the tree-lined avenues alongside pedal-driven rickshaws, just as in any other Indian city. And yet Chandigarh is still unique, and it is curious to note that this concrete city, with all its problems, its squatters, and its contrasts, is being swallowed up like a living ruin by the colourful jungle around it. And that it is still identified by its concrete, its much-criticised concrete, and its Rock Garden: an incredible garden of rocks, statues, waterworks and tunnels all made out of scrap construction materials and industrial by-products, put together over the past fifty years as Le Corbusier’s city has grown, by one Nek Chand, government official by day, subversive artist/collector by night, with the simple soul of a child, or a poet.

Cintya Concari

Illustrations by Roberto Marcatti