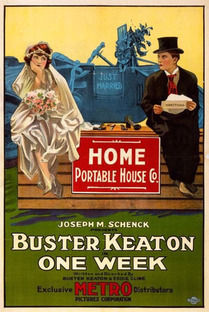

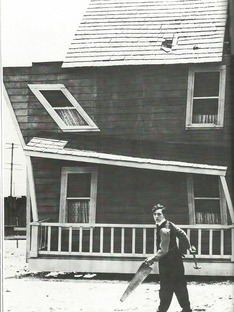

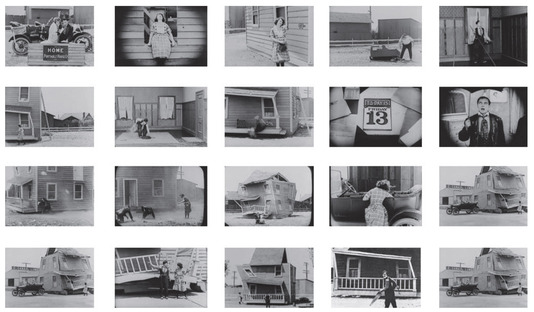

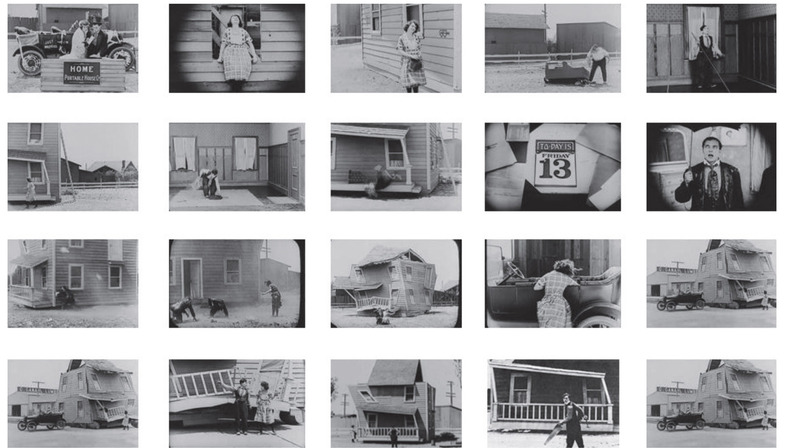

It is one of the legendary masters of silent cinema, Buster Keaton, who ironically offers us a parody of the new building methods of replicable catalog houses, pre-cut and ready to be sent on mail order. Kit houses, born in America around the first thirty years of the nineteenth century, gradually became very popular. There are three films that Keaton dedicates to this new visionary mass architecture suggesting a reason of reflection on these pioneering homes, making the sequential construction process a source of endless accidents, ever more disastrous. 'One Week', the first of the trilogy, sees Buster as an actor, as well as, a director, receiving as a gift from an uncle, on the occasion of his upcoming wedding, a prefabricated 'do-it-yourself' house. The house should presumably be built in 'a week' but a rejected suitor for jealousy secretly mixes the numbers of the packed crates. We will witness a series of catastrophic results in a crescendo of hilarity: doors instead of windows that open onto the void, sanitaries mounted on the exterior and the result of a completely lopsided final configuration, up to the closing shot that sees the groom walking away with his partner, after placing a ‘FOR SALE' sign, with the construction instructions attached, over a pile of stacked remains.

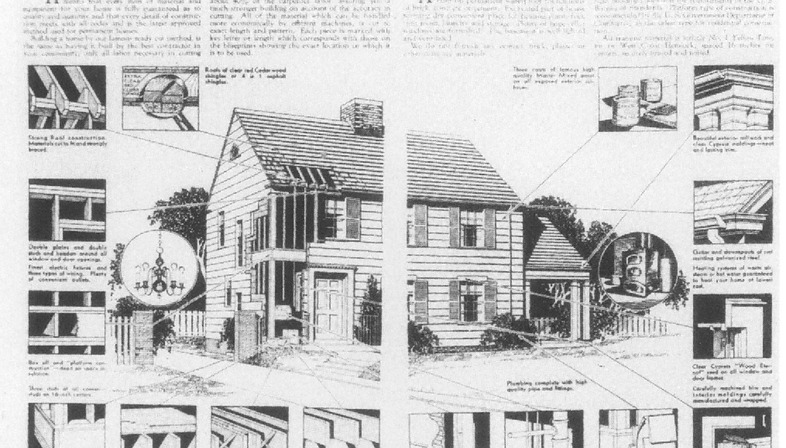

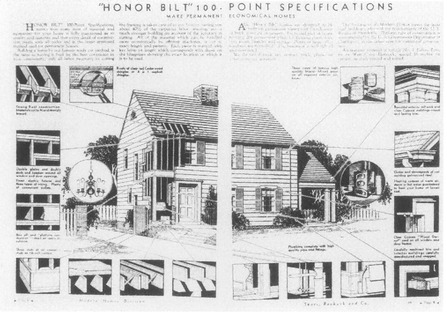

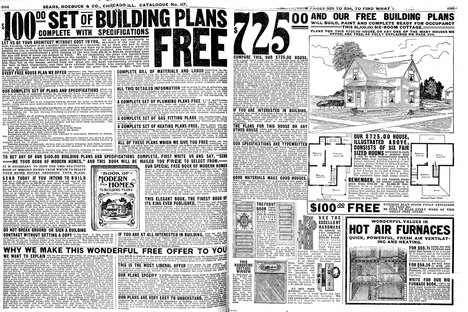

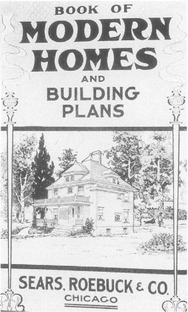

In these assembly processes presented in a humoristic and bizarre way, there is a very precise allusion to a company that at that time was selling a huge number of standard catalog homes. Sears, Roebuck and Company with its 'Catalog Modern House', represented a true authority in the sector and was able to offer the customers very affordable purchase costs, thanks to the capability to produce in quantities the materials and to halve construction times, with the same quality as traditional residences. The benefits were genuine, but Keaton created paradoxical circumstances by interpreting new technological currents that he sensed would likely help an on-going change. Trends of greater flexibility, closely related to future housing needs. Defined by someone as a 'visionary architect' and in his own words as a 'failed engineer', he proves to have overcome canonical models towards a new type of design mobility. In fact, he often proposed in his films a kinetic house, without foundations, completely electrified internally and mobile in the true sense of the word. The prefabricated house of Sears was therefore chosen not to move a condemnation but rather as a starting point for discussion on the fantastic story just begun, that as a challenge to the reductive notion of architecture, permitted to foresee amazing, surprising outcomes.

Sears, Roebuck and Company, ‘Catalog Modern House’.

Home Delivery, in its prodromes anticipated by a kind of prefabrication in support of the expansions of the colonial empires, such as Great Britain and France, represented a dream that involved architects of different generations with the aim of combining needs and innovation. As Barry Bergdoll, who curated an exhibition on this type of construction for MoMA in 2008, explains: “In architecture, the history of prefabrication is, in some senses, the history of modernism. The prefabricated house continues to be one of architecture’s most radical pursuits. Prefabrication is a reflection on the house as a critical agent in the discourse of sustainability, architectural invention, and new formal research”.

From assembled and transportable houses to the tallest prefabricated towers in the world, such as the two 56-story twin blocks, recently designed, that will see their birth in Singapore by 2026, our planet, densely crowded and severely polluted, has perhaps found a lighter footprint in the prefinished, a modus vivendi more in accordance with the environment and less impacting from an eco-sustainable point of view. By questioning the new frontiers of living together, considering climate change, avoiding waste of resources in the name of respect for an economy, which looks at the 'community' with greater 'equity', the architects, in significantly increasing number are re-evaluating modularity as a new horizon, that, contemplating technology and nature at the same time, promises to satisfy the aspiration for a better life.

“The ambition is to resolve the housing crisis with affordable, livable, and sustainable solutions,” affirms Sinus Lynge, partner of EFFEKT, a group of architects from Denmark, a region where many are facing this challenge with surprising versatility and just as much dedication. It is a whole new generation of very young, courageous and attentive to the natural environment, which is standing out not only for the pleasantness of the aesthetic aspect of their proposals but above all for a sincere research aimed at realizing a healthy collective life, variegated and made up of intergenerational relations, as it should be intended. Relevant is the quantity of new homes demanded with growing insistence due to the increasing global population, and the reduction in number of family’s members, and we have not to underestimate that to afford one of them is becoming a privilege of an increasingly limited percentage of people. There are currently many specialized companies that are concentrating on the goal of providing affordable, sustainable houses, fast to build, with extremely diversified layouts and combinations, meeting nearly zero-energy. Trying to optimize the various convenient aspects and the potential of prefabrication, thanks to a technology become incredibly sophisticated, with the aid of 3D printing and robotization, pushing the limits of design and materiality, could potentially be stemmed the housing crisis, with proposals not temporary but able to satisfy multiple awaiting needs, as the social requirements in support for the community, the economic imperatives and of course the environmental issues.

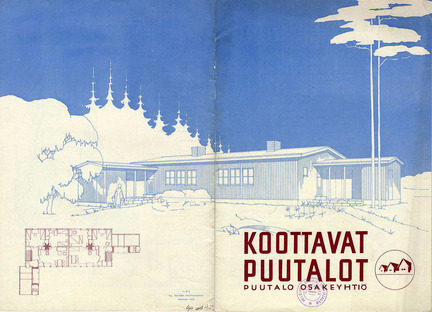

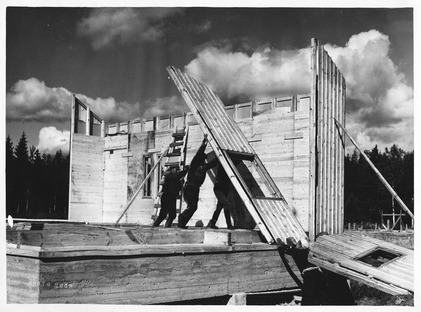

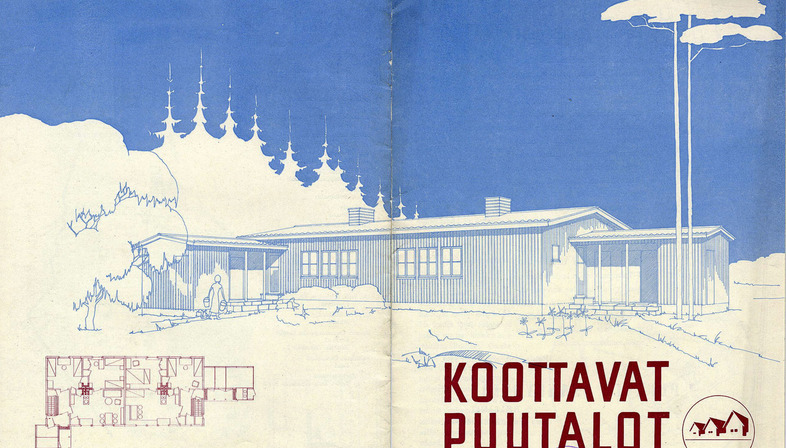

Puutalo Oy, Finnish Pavilion with 'New Standards', 17th Architecture Venice Biennale. Photo of Finnish Pavilion from Elka Archive.

Puutalo Oy, Finnish Pavilion with 'New Standards', 17th Architecture Venice Biennale. Photo of Finnish Pavilion from Elka Archive.

Lisbona,1755, painting of the devastation of a violent earthquake and tsunami. Photo di Wiki/Public Domain

The use of this apparently new technique tickled the inventive spirit of various personalities of that period, between the end of the 19th century and the Second World War, remaining, however, limited to architectural experiments that represent important stages, but will not see an application on a significant scale until the end of the war. Only then the need to rebuild massively imposed prevailed, due to the urgency to provide a roof for thousands of families left homeless. Cases of immediate emergency were accompanied by a rich experimentation, characterized by careful research of materials that in the 60s and 70s turned to the unanimous use of large modular concrete panels.

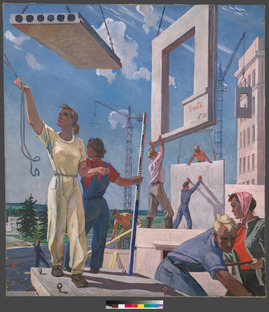

Gerbert Rappaport Cherrytown, Cheryomushki. 'Flying Panels - How Concrete Panels Changed the World' Exhbit. Archivi FN.

In the various parts of Europe prefabrication presented the most appropriate response that the general desolate picture of destruction, decay and shortage of housing at the end of the war requested but also witnessed very different reactions and uses, determined by the ideological postulates of the diverse political ideas. In Italy, the various exhibitions of the Triennale di Milano, starting from the 1930s, began to address the theme of modularity, with a series of initiatives investigating aspects capable of enriching a "customization", intended as a language not only of pure functional convenience. There will be a period preparatory to real industrialization with pioneering attempts successfully studying and prototyping the new method on an experimental basis, addressed to the final effort of affirming artistic authorship. Italian architects and designers had to try to adapt the limited diffusion of their products, characterized by craftsmanship excellence, to the recent expansion of the market that, providing for a wider audience, required high quality products at affordable costs. A close collaboration between the world of creativity and that of production was therefore gradually becoming more and more indispensable.The exhibition of the 10th Triennale in 1954 paid particular attention to those prefabricated construction elements, also belonging to other markets, such as the French and English, progressively more and more refined, which could satisfy high technical requirements, but also propose stimuli for compositional freedom. The new technique definitively entered the common semantics with the mechanization of construction sites.

Virginia Cucchi

Credits:

Photos:

cover: 'Flying Panels - How Concrete Panels Changed the World' Exhbit. Archivi FN. Photo of Aleksandr Deyneka Building Peace 1960 sketch, Mural Mosaic First National Art Exhibition of Soviet Russia, Tretyakov Gallery

01-04: One Week, Buston Keaton's Film.

05-07: Sears, Roebuck and Company, ‘Catalog Modern House’.

08-11: Puutalo Oy, Finlandia. 'New Standards’, 17° Biennale of Architecture, Venezia. Photo of Finland Pavilion/credits Elka Archive.

12: Lisbona,1755, painting of the devastation of a violent earthquake and tsunami. Photo di Wiki/Public Domain

13-15: 'Flying Panels - How Concrete Panels Changed the World' Exhbit. Archivi FN. 14- Gerbert Rappaport Cherrytown, Cheryomushki, 1963, 15- Sune Sundahl Installation Large Concrete Panels in Residential Buildings