22-02-2022

HOMELESSNESS

homelessness,

John Cary, architect and writer but above all activist, dedicates his energies to the promotion of an ‘Architecture capable of conferring Dignity’ to people who live marginalized and in conditions of extreme difficulty, a stigma that painfully afflicts this our society. Executive director for several years of ‘Public Architecture’, a San Francisco non-profit organization, founded in 2002, with the aim of encouraging nationally, through '1% Solution' program, architecture and design firms to devote this negligible percentage of their billable hours to pro bono service, in 2005 he participated in a small project that had a wide resonance. A local documentary filmmaker, Anna Fitch, got in touch with his agency, suggested an idea that met their full acceptance. The proposal was to build in just six weeks, in time for the United Nations World Environment Day, a temporary demonstration house made entirely of salvaged materials, filming the various processing phases, which then will be broadcast on the National Geographic Channel. Thanks to volunteers, an extremely heterogeneous team, the initiative started, seeing, even if amidst delays and setbacks, its completeness within the established deadline.

John Cary, architect and writer but above all activist, dedicates his energies to the promotion of an ‘Architecture capable of conferring Dignity’ to people who live marginalized and in conditions of extreme difficulty, a stigma that painfully afflicts this our society. Executive director for several years of ‘Public Architecture’, a San Francisco non-profit organization, founded in 2002, with the aim of encouraging nationally, through '1% Solution' program, architecture and design firms to devote this negligible percentage of their billable hours to pro bono service, in 2005 he participated in a small project that had a wide resonance. A local documentary filmmaker, Anna Fitch, got in touch with his agency, suggested an idea that met their full acceptance. The proposal was to build in just six weeks, in time for the United Nations World Environment Day, a temporary demonstration house made entirely of salvaged materials, filming the various processing phases, which then will be broadcast on the National Geographic Channel. Thanks to volunteers, an extremely heterogeneous team, the initiative started, seeing, even if amidst delays and setbacks, its completeness within the established deadline.The creation, ‘ScrapHouse’, will amaze for the ingenious solutions adopted: walls covered with sheet metal fragments of sheet metal and road traffic signs, floors made of wasted solid wood doors or covered with pieces of leather and leftovers from upholstery works. Everything recovered from landfills and scrapyards or made available by public institutions finds an attractive location. The final result is particularly brilliant, the extravagant collage of pieces destined to remain unused has a catalyzing force from an aesthetic point of view, highlighting possibilities and launching challenges that embrace the field of green building and recycling but also reserving values which transcend that of environmental sustainability, such as the importance of a collective action which, animated by common intentions, achieves this very significant outcome.

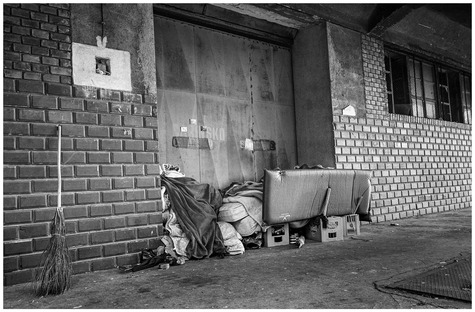

Cary is satisfied with the accomplishment which, although modest in size, appears quite provocative but, as he will confess in an article he will later write, a sense of bitterness, not to say embarrassment, will accompany him for a long time, having never been able this house to be used, offering shelter in a city where every night, as he himself claims, hundreds or thousands of homeless people sleep on the street or in shelters. The problem that embitters Cary is an age-old plague that torments especially all the richest and most densely populated city centers and in this 15-year period, which has passed from his considerations, the question of a home for all has definitely worsened, showing deeply threatened what has long been commonly considered a right in most countries. Then there was this terrible epidemic that has affected everyone, putting economic situations to the test, making the most fragile ones dramatic. The profound inequities within our society have exponentially shown themselves, requiring with ever more urgency the necessity

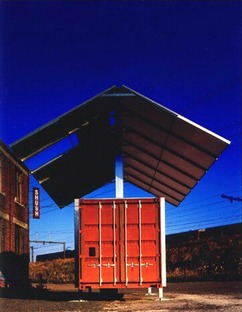

Sean Godsell, at the beginning of a profession that he has always considered of high social involvement, proposed in 1985 'Future Shack’, a prototype which, exploiting the advantages of the universal nature of the container, suggests a possible mass production of easily relocatable emergency homes, able to satisfy a wide variety of basic demands: from post-natural disasters to temporary housing. Melbourne, regarded as one of the world's most liveable cities, at that time appears to have "become an epicenter of the homeless" and Godsell, witnessing this gradual deterioration, feels motivated to start an aid program that intends to adapt the static elements of public furnishings to the dynamic part of the urban fabric. The bench that offers a seat in the park during the day conforms to the dual function of refuge at night, with the addition of a weatherproof pop-up roof, equipped with a survival kit, as the 'Bus Shelter House', when public transport stops. These three self-financed prototypes received highly praiseworthy comments from critics and 'Future Shack', which gained a special mention from the President of the American Institute of Architects, has its model exhibited at the Cooper Hewitt Design Museum at the Smithsonian. Institute in New York.

However, from an implementation point of view, which represented the real aspiration of the young architect, these simple and economic proposals, which did not pretend to be definitive, did not please the planning authorities, perhaps causing a strong embarrassment, for not having found a more decent way to face and resolve so many painful human emergencies. The architect, endowed with a very tenacious temperament, irony and a lot of unconventionality, particularly frustrated by government immobility, thought of an act as original as provocative, presenting his 'Park Bench House' to the selection of the Best House award of the Australian Institute of Architects. A gesture dictated by the desire to ennoble a modest elaborate that did not meet the deserved consideration and did not arouse the supposed social responsibilities. There were reactions from those who indignant, trying to discredit the true meaning of the initiative, declared it was a spectacular self-referential attempt in search of publicity but, apart from these inappropriate allegations out of place, the humble park bench will cause a large range of equally creative and philanthropic proposals from designers. We cannot anyway expect architects to solve homelessness, ‘we need’, as Godsell rightly concludes at the end of this long, tiring journey, emblematic of the adversities and hostility by which it is studded, "a change of paradigm, a social change, not an architectural one”.

His kinetic benches, which can be transformed into beds for the night with a little light and a minimum of comfort, proposals that for many reasons have been considered by the authorities inappropriate, have remained unchanged over time if not worse. A series of measures, let's say deterrents, part of that public 'hostile', or 'defensive architecture', basically devised to discourage vandalism have provoked even greater difficulties to the miserable existence of those seeking refuge in a park or along the road. With no intention of offering themselves as alternatives to spend overnight in reception centers but rather designed as temporary thermal shelters, to prevent hypothermia deaths in the coldest winter nights, two projects arise from the dedication of different creators: 'Iglou' and 'Ulmer Nest'. Both prototypes, a pop-up igloo, foldable and light, made of polyethylene foam and aluminum coating, easy to transport and assemble, and "a pod for sleeping", in wood and painted metal, closed and isolated, powered by solar energy. The hope is that a network of these antifreeze capsule nests, warm individual homes, can spread, scattered in parks and other places of need in the city.

Since those first efforts to raise awareness, which have been mentioned and date back more than 30 years ago, a global response, that could permanently and in most cases decorously satisfy this increasing reality, has not yet been reached. In Europe over 700 thousand people, unfortunately in drastic growth, are forced to live on the street: the European Parliament has invited on the European Commission to develop national strategies by 2030, ensuring funding and unanimously adopting the 'housing first' model, which, contrary to more 'traditional' approaches, plans to transfer as quickly as possible homeless people to permanent accommodations. Decent and possibly independent accommodation: a decidedly opportune perspective which unfortunately, despite the substantial differences that distinguish the member states, faces a situation common to all countries: the impossibility of affordable prices that allow for forms of hospitality without marginalizing in desolate and hardly served areas.

With the adoption of the same 'parasitic' system, the Norwegian architect Andreas Tjeldflaat of Framlab creates an interesting honeycomb pattern, inexpensive, flexible and easy to assemble and disassemble. New York City has reached the highest levels of homelessness and it is almost impossible to offer spaces of safety, cleanliness and comfort to these less fortunate people. It is estimated that over 61,000 people sleep every night in city's homeless shelters and thousands more on the streets, in the subway and in other public spaces. The experimental project 'Shelter with Dignity', ‘SwD’, planned for 'vertical lots' represented by inactive walls, "tries to capitalize on this vertical land". It is made up of modular hexagonal cells which, with a light load-bearing structure, hook to a simple scaffolding and, placed side by side, form clusters of suspended micro-neighborhoods. The architect, who desires to improve social and environmental resilience, exploits the most flexible and economical design systems: the prefabricated units, external shells in steel and oxidized aluminum in consideration of the exposure to different weather conditions, present interiors covered in plywood, warm and soft environments, friendly and welcoming, insulated and well ventilated. The 3D printed modules allow to integrate in the minimum space all the necessary tailor-made.

Virginia Cucchi

Credits:

ScrapHouse, John Cary

Park Bench House & Future Shack, Sean Godsell, Photo Earl Carter

Igloo, Geoffroy De Reynal

Shelter with Dignity, SwD, Andreas Tjeldflaat di Framlab

Cover, “Who’s next. Homelessness, Architecture and the City”, Exhibition at Technical University of Munich / FN Archive

01, Photo by Rockinrita/FlickrCC

02, Photo by KSPhoto/FlickrCC