Recently has been released ‘Nomad: In the Footsteps of Bruce Chatwin’, a film that traces in documentary terms travels and interviews of a writer I loved very much, who has allowed me to experience truly special places through his stories. The topic seems of great relevance in a moment when we hear of the figure of Nomad with increasing insistence and with a new meaning, no longer associated to the idea of an eccentric and nonconformist outsider, but as an individual who, abandoned behaviors and codified parameters of a disappearing tradition, accepts transience with extreme adaptability. We are witnessing the gradual annihilation of reference points and the redefinition of models that we considered consolidated, in an incessant alternation of proposals that annul each other in a game of unbridled innovation. Instability has become the norm that governs our existence and the future lies ahead with a very elusive identity. I fear that precariousness will afflict those who will not be able to adapt to the growing demands of a progress that appears mainly as technological.

Recently has been released ‘Nomad: In the Footsteps of Bruce Chatwin’, a film that traces in documentary terms travels and interviews of a writer I loved very much, who has allowed me to experience truly special places through his stories. The topic seems of great relevance in a moment when we hear of the figure of Nomad with increasing insistence and with a new meaning, no longer associated to the idea of an eccentric and nonconformist outsider, but as an individual who, abandoned behaviors and codified parameters of a disappearing tradition, accepts transience with extreme adaptability. We are witnessing the gradual annihilation of reference points and the redefinition of models that we considered consolidated, in an incessant alternation of proposals that annul each other in a game of unbridled innovation. Instability has become the norm that governs our existence and the future lies ahead with a very elusive identity. I fear that precariousness will afflict those who will not be able to adapt to the growing demands of a progress that appears mainly as technological.

We live days dominated by anxiety and a widespread sense of discontent. Chatwin himself was victim of this condition of uneasiness and, embittered by a feeling of being used by an extremely cynical world, tried to find places less contaminated by such indifferent selfishness. When he travelled to Africa, invited by a friend, he encountered for the first time the civilization of the Nomads, a reality that will continue to fascinate him throughout his life. The few words he wrote about his nomadic guide remain as emblematic testimony of how intrigued he was: “My nomadic guide carried a sword, a purse and a pot of scented goat's grease for anointing his hair. He made me feel overburdened and inadequate…”. This capability to be happy and satisfied with the essentials seduced him to the point of devoting himself entirely to this phenomenon with the ambition of unravelling a metaphoric proof of human’s continuous roaming of the earth as a genetic impulse. The fundamental question: "why do men wander rather than stand still?", perhaps inspired by his own inability to stay in one place for more than a month, remains unanswered, but his observation of the nomadic populations, which don’t ever indulge in anything superfluous, will suggest, at the end of his reflection, that human beings were destined to be a migratory species, and once they settled in a permanent location, their natural urges "found outlets in violence, greed, status-seeking or a mania for the new.”

If we consider Australian Aborigines, equally loved by the writer, we can’t find any similar behaviour in the history of humanity, much less in contemporary man. “They trod lightly over the earth; and the less they took from the earth, the less they had to give in return. They had never understood why the missionaries forbade their innocent sacrifices. They slaughtered no victims, animal or human. Instead, when they wished to thank the earth for its gifts, they would simply slit a vein in their forearms and let their own blood spatter the ground”; in this description of Chatwin we read the unbridgeable gap that separates us from these populations, from their customs and habits, translating how intimately innate it was in them to feel integral part of the cosmic breath which allows the perpetuation of the life’s cyclical flow, embracing sun, trees, water, stars and the whole universe.

Unfortunately, it didn’t happen the same in the evolution of this anthropocentric civilization that saw man treading with a triumphant step, leaving very evident traces, far from the light footprint that, in the name of respect, has left signs of love and of harmonious balance. A truly arrogant attitude that is actually suffering what an impoverished and mistreated nature has reserved with as much inexorable and merciless violence. There are signs of remorse, followed by promises of change to come. As someone has said, after the explosion of man into the world, we are witnessing the implosion of the world into man. It seems that many are experiencing the urgency to be more in tune with that diffuse network of interdependencies that makes up our planet. When is lacking the beneficial regenerating contribution that impregnates our spirit with vital energy and desire to live, those ancient sentiments for a primordial world, which we can no longer perceive, emerge with the overwhelming force of a great regret.

We are part of a century, in which a consumerism pushed to an exasperated degeneration is causing a flattening and a sort of generalized homologation. Following this widespread, prevailing fetishism to possession and materiality, which has provoked phenomena of voracious and compulsive bulimia, we are seeing the post excitement phase, characterized by a strong depression.

A new nomad, who has little to do with the pastoral and ethnic groups or hunters, searches with nostalgia for a sort of initiatory journey towards a nature and a way of life connected by a lost sacredness, which cannot be found in traditional forms of religions. And more and more frequent the tendency is to buy an old four-wheeled means of locomotion, whether a truck, a bus or a van to transform it into a real traveling house, and to live an adventure of a few months or perhaps years. Are we projected into the future or are we observing a nostalgic return to the recounts of tales of Jack Kerouac 'On the Road', to the movements of the hippy community along Mid-America with flowered station wagons? To the years following the World War II, when American families, driven by the enthusiasm of a relative economic well-being, pursuing the mythical American Dream of the 'perfect family', settled in the suburbs built around the major cities.

In the current era marked by technocommunication, the stability and rigid compartmentalization that have characterized with sedentary lifestyle the modernity, which sought to control chaotic aspects of life with rules, order and durability, appear to be an inadequate behavioral style. This increasingly transitory reality offers a continuous rapid alternation of parameters, technological and scientific transformations, changing visions of urban and suburban landscapes, creating insecurity and worries in us, subjected to a sort of uninterrupted disorientation. Linked by a dense structure of powerful technological connections, we are perpetually in a virtual contact, even if every our action and the way we communicate have been reduced to the essential. Pressured by the lack of time, that makes us feel constantly in delay, we resort to smiling or crying emoji to express our moods, in order to save maybe a few seconds. Technocracy is now of such magnitude to let us foresee the disappearance of institutions and entire categories of workers, a real revolution in the forms and habits of life and work. The new technologies are forging our existence and with increasing intrusiveness will align the working landscape. Are emerging behaviors and professional models, inspired by greater independence and flexibility than those based on a certain static nature that we have become accustomed to: the new evaluation criteria will refer to productivity rather than presence and with the introduction of smart working the defined hours will leave space for self-management.

From the neural interrelated network of cyberspace, has evolved the digital nomad, a sort of predecessor of the man that some predict will live the millennium to come. According to many, a practice is renewing which reveals one of the most ancient manifestations of human sensitivity for its unusual ability to adapt to sudden and extreme changes. I read of an hypothetical new tribe, but with substantial differences from the tribal clan of the nomad of the past, made up of experts in technology and digital practices, who, without borders and without a territory, thanks to the kit that constitutes their electronic appendages, a PC, a satellite phone and a few other accessories, can be connected anytime and anywhere in the world.

It seems that these digital nomads, deciding to take advantage of their professional training, their easy inclination to adaptation and autonomy, will redeem their existence and reinvent it thanks to a new way of moving that could allow them to feel happier, to build a better life, freer, weaving more authentic relationships in terms of both work and human cooperation, in a rediscovered symbiotic relationship with the environment. These errant knights of digital civilization, without rejecting the different models and scenarios of development that envisage the possible conquests of the sector of which they are gurus, wish to regain possession of personal rhythms and needs, freeing themselves from the ambiguous contamination that makes particularly difficult to distinguish life from work. ‘Great border crossers’, multimedia specialists, but also multiethnic and multicultural, can rightly be defined global digital nomads. As real expert surfers, they ride with extraordinary agility and dexterity the waves of data ever more gigantic in a sea made of international interrelations and contaminations but also show a side of their character that discloses them as dreamers. They live an ideal, which they wish to achieve, and, aware of all the responsibilities and possible consequences, they approach it with self-confidence but also ready to question themselves: success is certainly important but, analyzing their philosophy of life, even more the experience they will have the opportunity to live.

They abandon that exasperated ego-centrism and individualism that threaten in our society to erode and break up the sense of community and communion with others, open to listen to one another, in the attempt to nurture interpersonal relationships that can grow into real cooperation. Leaving aside professional rivalry, they aspire to organize a form of collaborative involvement that sees the participation of others, achieving a real team work, that is not a hierarchical, pyramidal structure controlled by a leader but horizontal and interactive one. And for some of them the ideal would be to create small communities, a sort of enclave perhaps inspired by the idea of the kibbutz, with a postmodern and multiethnic imprint, creating, as the nomads did, those oases that dotted their harsh and difficult paths, where, in the shade of some plants, to be able to quench their thirst and recover from the efforts with their animals. The lost sense of identity and collectivity pushes them to seek a sense of belonging to a group who, united by common interests and intentions, freely aggregate and regulate themselves, responding only to their personal sense of responsibility.

These types of enclaves that some imagine can germinate from neo-tribes of digital nomads and certain oases scattered in the desert, able to survive as real ‘autopoietic ecosystems', lead me to follow a path back to an exemplary testimony. Arcosanti, a small city still in progress, regulated by a metabolism made of frugality and interactivity, born from the desire to offer a possible remedy, a model of cure for the ever-expanding, dispersive American suburban metastases.

What this future of ours will be like is difficult to predict: this form of digital nomadic life could be one of these many aspects. And if nomadism in its most varied manifestations will take hold more and more, I hope it will represent not a radical break but a phase of rethinking and an evolution towards a better society. Nomadism, in its ancestral meaning, has always ennobled man, who respected the relationship with the community and nature, and we must hope to see it always pursued in its free and more social form of life.

Virginia Cucchi

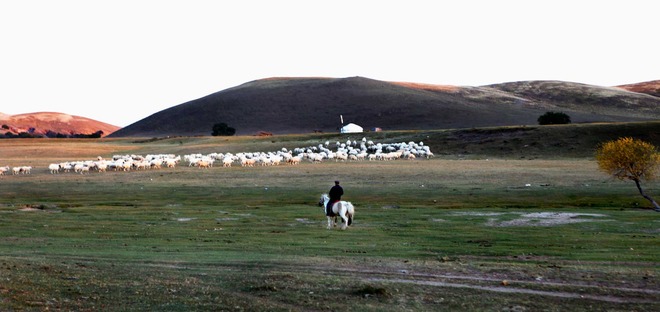

Photo: Mongolia, Virginia Cucchi