22-06-2021

ARCHITECTURE & COMICS

Peter Cook, Peter Reyner Banham, Rem Koolhaas, Le Corbusier, Archigram, Hans Hollein,

Warren Chalk, Frank Oscar King, Winsor McCay.,

Paused...

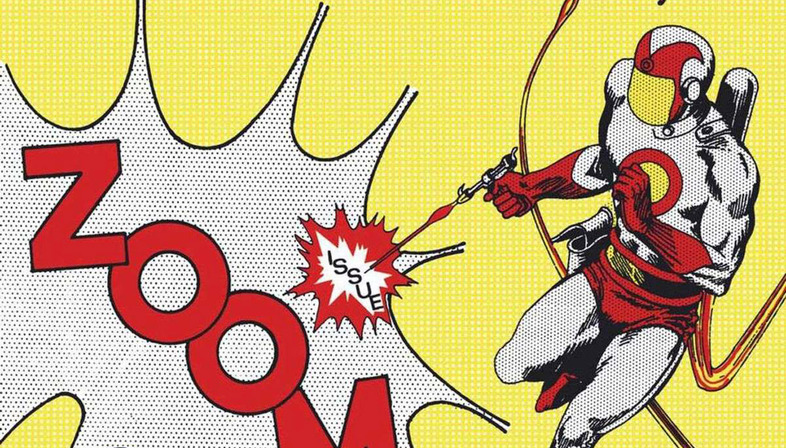

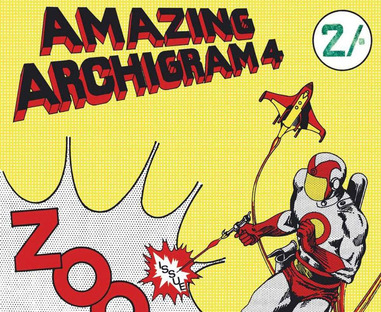

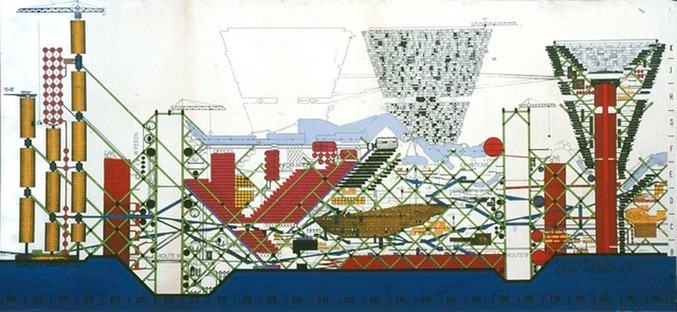

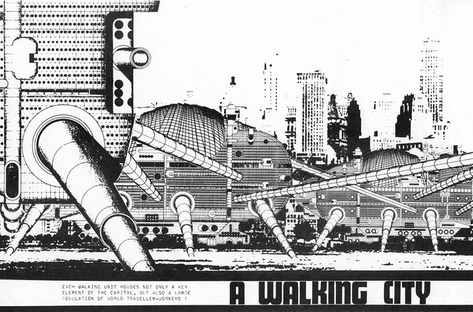

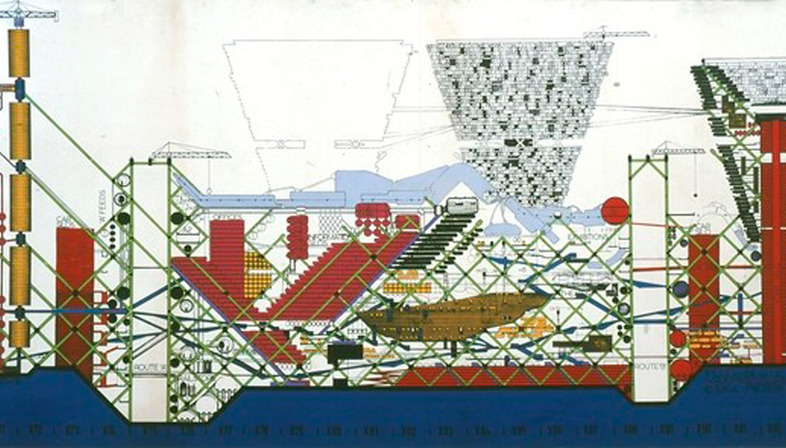

Architecture has always fundamentally been an autonomous discipline that has not easily accepted narrative tools connected with experimentation in its expressive syntax. Even architects gifted with a superb hand were often not appreciated as they deserved especially by their contemporaries and many of them frequently kept their virtuosity separate from canonical forms of representation, reserving their talent to exercises in the free time. However, there have been several radical movements that have alternated and expressed their disappointment towards presentations that connoted the architectural buildings with static traits, relegating them to a rigid isolation, deprived of that dynamism due to them as living organisms and active parts of life. Archigram collective, for example, which from the very beginning through the name, a combination of the words "ARCHItecture" and "teleGRAM", heralded the intent to communicate with speed and strong impact, utilised for their futuristic creations a graphic code based on the Marvel Comics’ covers and the Pop Art style. They tried to redefine architecture, by translating into the two-dimensional paper design an hypothetical environment which they had imagined “if planners, governments and architects were magically able to discard the mental impedimenta of the previous age and embrace the newly developed technologies and their attendant attitudes”.

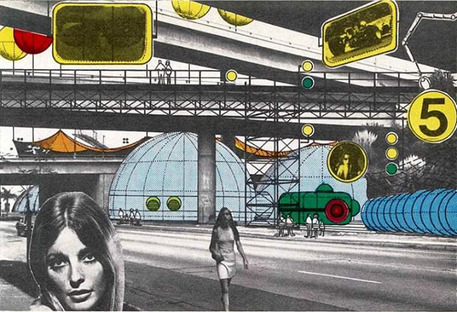

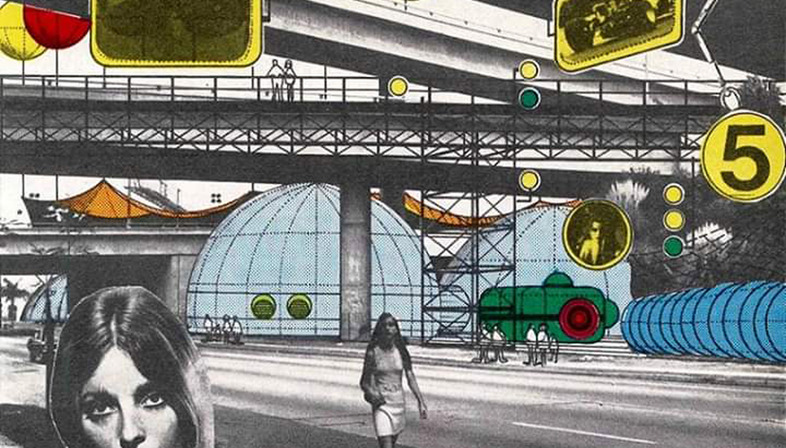

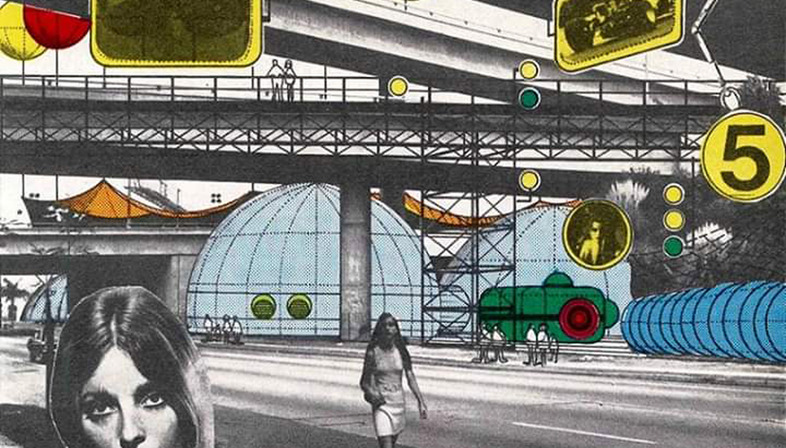

They felt for sure a certain self-referential gratification about the effects that the daring and decidedly provocative medium they had chosen would have had, as Peter Cook admits in an interview: "it gave us great pleasure that the borrowing from comics would upset the normal architect. “'You should be correct, you should be politically correct in a certain way, you should draw in a certain way.’ We found that stultifying! And we used to say very often, ‘“This will upset them!’” . They also used collages made of figurines, mostly women, cut out of magazines and then pasted into the foreground, without the typical function of providing a scale but leaving the buildings in the background visible, as only reference for the activities.

Archigram's Collage, Architectural Design. 1969 / Archivi

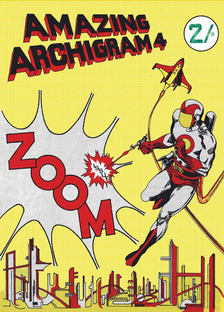

It will be a critic to consecrate the catalyzing force of the unusual language adopted by the rebel group. Peter Reyner Banham, referring in particular to “Space Probe!”, the work created by Warren Chalk for the magazine 'Amazing Archigram 4 / Zoom’, will contribute to their success and their international fame with these words: “If the passage falls below the levels of ponderous literacy and pedantically accurate spelling… the use of imagery has a knowing exactitude which overleaps conventional architecture-magazine rhetoric of the period, by-passes the reader’s normal verbal defense mechanisms, and thus produced a distinct shift in sensibility.”They felt for sure a certain self-referential gratification about the effects that the daring and decidedly provocative medium they had chosen would have had, as Peter Cook admits in an interview: "it gave us great pleasure that the borrowing from comics would upset the normal architect. “'You should be correct, you should be politically correct in a certain way, you should draw in a certain way.’ We found that stultifying! And we used to say very often, ‘“This will upset them!’” . They also used collages made of figurines, mostly women, cut out of magazines and then pasted into the foreground, without the typical function of providing a scale but leaving the buildings in the background visible, as only reference for the activities.

Archigram's Collage, Architectural Design. 1969 / Archivi

‘Amazing Archigram 4 / Zoom', Archivi/'Arkitekturstriper: Architecture in comic-strip form', 2016, Courtesy of The National Museum – Architecture.

Archigram members of course wanted to impose themselves on the world for a way of thinking and not just for a style, with which they had decided to present architecture, but the courageous use of comics caused a resonance that still persists and above all had the capability to renew interest in the genre, claiming its value as a cultural interlocutor. Cook recalls a comment by Nick Grimshaw, his student at the time, which attests to the sensation caused by the publication of "Plug-in City" in the color supplement of the ‘Sunday Times’: “We all saw this thing in the paper and we thought ‘What the hell is this lunatic teaching us?’”, but, "Some of us came around to it and started doing that sort of thing ourselves.”

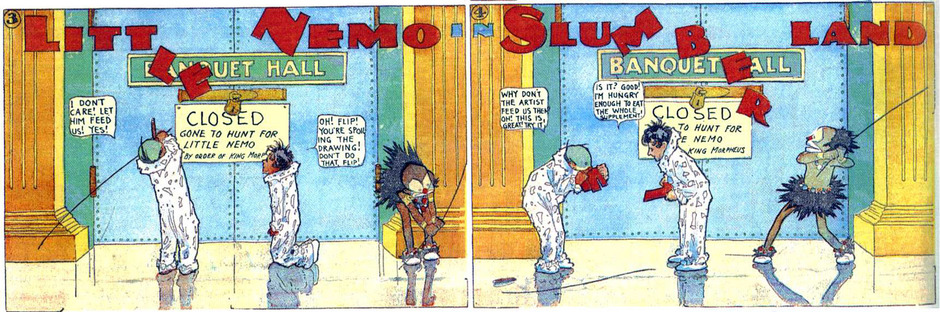

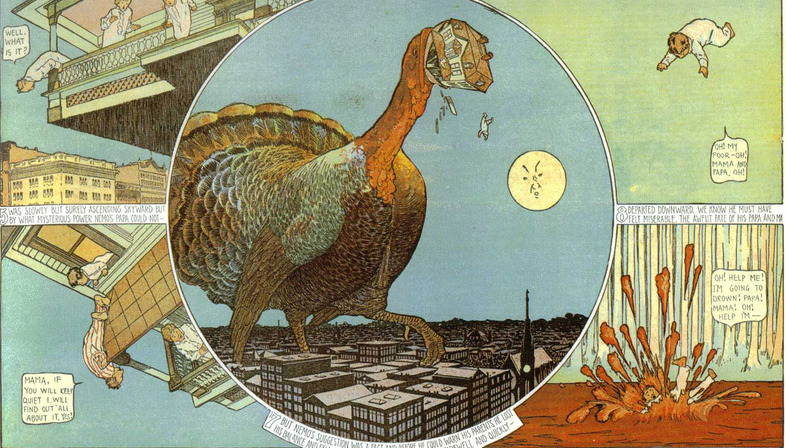

‘Little Nemo in Slumberland’, Winsor McCay.1908. Wiki/Public Domain

There have been many other attempts to contrast the persistent widespread disciplinary orthodoxy, imposing new theoretical and linguistic formulations and among these a special mention has certainly to be reserved to the subversive force exerted by the experimental movements of the Austrian and Viennese radical groups. With the contribution of the culture of media they tried a different approach and a rupture and rejection of modernist conformism and reductionism, which with its rigid formulation ‘form / function’ denied organicity and mortified creativity, relegating architecture to an underdeveloped level compared to the other arts. Hans Hollein, blurring the boundaries between different disciplines and claiming an 'absolute and free architecture', will proclaim: "Limited and traditional definitions of architecture and its means have lost their validity. Currently, the environment overall is the goal of our activities—and all the media of its determination: TV or artificial climate, transportation or clothing, telecommunication or shelter. The extension of the human sphere and the means of its determination go far beyond a built statement. Today everything becomes architecture”. 'Everything is Architecture' is the manifesto of a movement that will prefer experimentation in the field of visual arts. In the drawings and photomontages by Raimund Abraham, Hans Hollein and Walter Pichler, will be often inserted natural elements, as a way to affirm, against the artificial sterility of the functionalist city, the possibility of contaminations and a coexistence between natural and technological landscape, probably also with a concern for environmental problems, which were manifesting in those years, not contemplated by the radicalism of Archigram, enthusiastically focused towards a hyper-technological future.

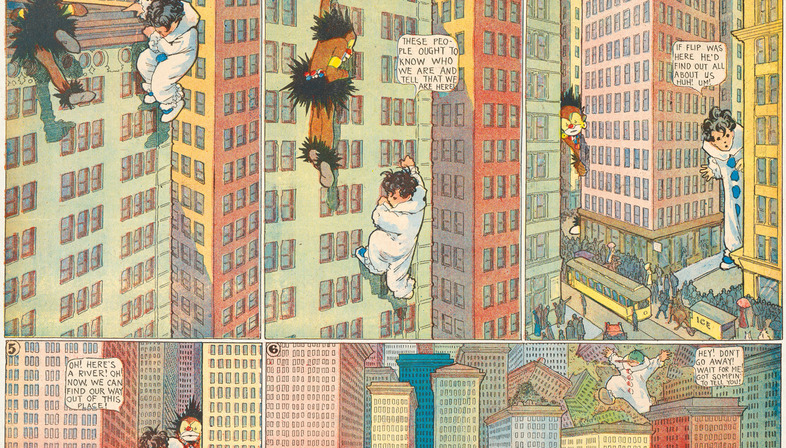

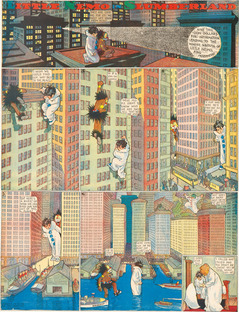

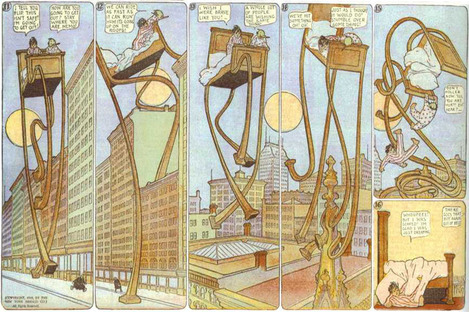

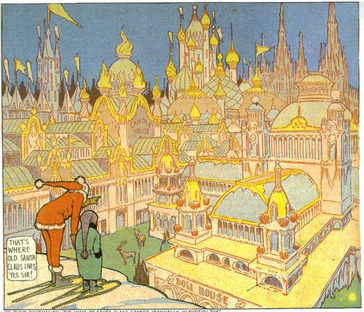

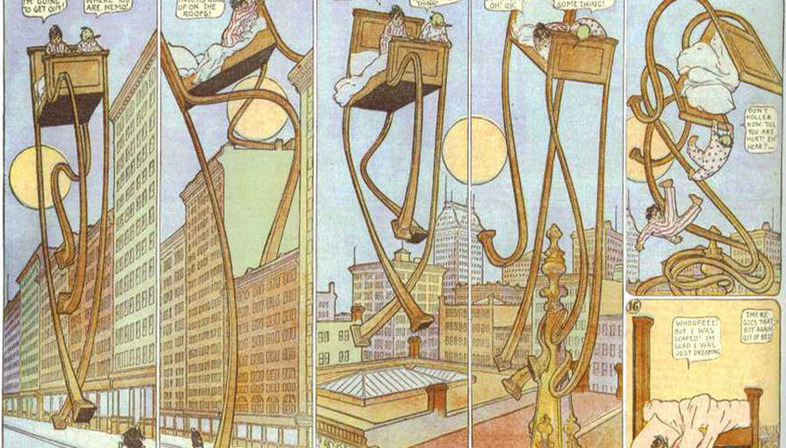

The first time a sort of cross-pollination is established between the architectural language and the ‘bande dessinée’ perhaps dates back to 1905, when in the 'New York Herald' appears 'Little Nemo in Slumberland', later renamed 'In the Land of Wonderful Dreams', a famous series, created by the refined imagination of the prolific American cartoonist Winsor McCay. The artist with great narrative and visual talent leads us through the extraordinary nocturnal journeys into the fantastic dream world of his little character, by breaking the rigid traditional structure. The shots focus on the elegant graphic quality of Art Nouveau scenographies that follow one another always renewed and surprisingly kaleidoscopic in their urban proposals: Little Nemo's flights take place between the buildings of Chicago, Manhattan and the fabulous kingdom of King Morpheus, inspired by the white stucco palaces of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. Temporal and spatial dimensions intersect with the result of a pioneering animation. Tables composed in the most complete freedom reproduce the uncontrollable evolution of the dream, alternating arrangement and dimensions, expanding and contracting according to the situation of the moment, using the contrast of colors to recreate the irrational gaps of the oneiric experience. The rhythm is controlled through variation or repetition, seeking special effects and emotional sensations, anticipating the cinematic dynamism with its typical inventions, such as tracking shots and camera movements. We will still have to wait decades before Sergei Eisenstein arrived with his attempts at editing the film. Abundance of details animate the surreal, imaginative settings of futurist cityscapes.

‘Little Nemo in Slumberland’, Winsor McCay. 1907. Wiki/Public Domain

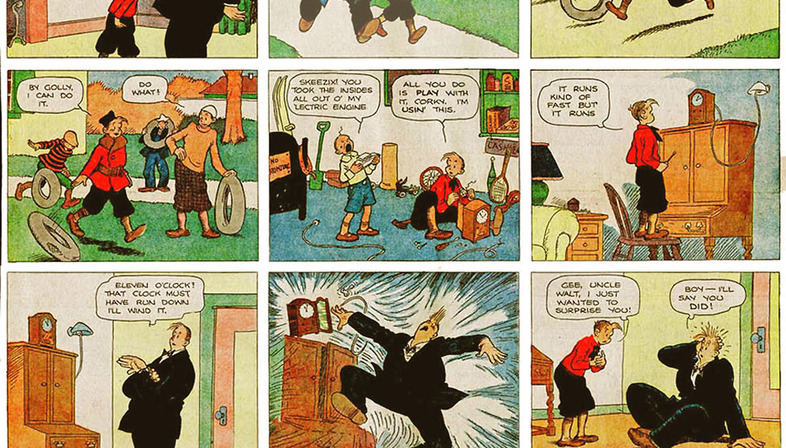

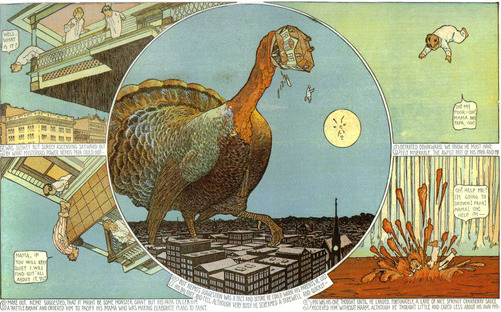

The search for real time continuity and the architectural representation in its smallest components are characteristics of another American contemporary, Frank Oscar King, who in his well-known 'Gasoline Alley', describes the adventures of friends and relatives who on Sunday repaired their automobiles in the alley behind their houses. An arial view, an almost isometric perspective, decomposed, ‘atomized’ in many panels occupies a whole page, embracing the events of the neighborhood, alternating with fixed protagonists, offering almost simultaneously the different moments of a comedy in its development.The iconic strength of the images created by the hand of artists from the most diverse currents will adapt to this new representative trend, interpreting and reproducing the reality in an explosive mix of fluid sequentiality and simultaneity. Abandoned the photographic precision of linear drawing, the public will experience increasingly engaging spatial-temporal representations and this ability to visually transmit movement is in line with the progressive tendency of many architects, who, revealing during these recent decades interest in communication technologies and strategies, have introduced time in their projects, following an evolutionary path.

Returning to that exchange between architecture and comics, someone has attributed the use of a sort of cartoonish storyboard to Le Corbusier in the 'Lettre a Madame Meyer', 1925, with which he communicated some concepts on the future design for that never-built villa, through a series of sequential views and footnotes. Le Corbusier read in fact during his childhood a travel book illustrated by the drawings of Rodolphe Töpffer, considered the Swiss father of modern comics and was so fascinated by these representations that he dedicated an article, the first in absolute on this artistic genre, published in an academic architectural magazine. But this reference remained quite isolated and it was 'Amazing Archigram', after several decades, echoing in a certain sense the British scene, in which comics were experiencing a new revitalization, to play a relevant, influential role in the architectural world.

The amusing and provocative suggestions of the avant-garde group with their mobile inventions, survival pods and allusions to a possible life in space struck, together with the beautiful illustrations for science-fiction comics of the period, the imagination of an architect who became in a certain sense one of the international reference figures of high-tech architecture, making the most recent technologies and materials a prerogative of his work.Norman Foster, Paul Rudolph's pupil at Yale and early collaborator of Buckminster Fuller in various creations, currently engaged in the design of entire cities and a lunar habitation, loves to communicate the performative solutions of his radical ambitious projects thanks to those cartoonists and illustrators who had excited him so much during his youth, not disdaining to transmit messages related to his buildings framed in little puffs of smoke. Over the years, he has always dedicated notes of admiration to artists involved in the most innovative visual communication, as he did with the young Giacomo Costa, personally supporting initiatives to help new visual languages belonging to the 'ninth art' used in collaboration and for the diffusion of architecture. He wrote a preface for Augustin Ferrer Casas' aquarelas for 'Mies', the recent graphic novel, that traces the life and work of Mies van der Rohe, from his early days in Berlin to the Bauhaus to his move to Chicago.

Virginia Cucchi

Credits:

Cover, 10: ‘Amazing Archigram 4 / Zoom', Archivi/'Arkitekturstriper: Architecture in comic-strip form', 2016, Courtesy of The National Museum – Architecture.

01: Plug-in City. Archigram, Peter Cook/via Archigram Archivi

02: Archigram's Collages, Architectural Design. 1969 / Archivi

03: Archigram, Walking City / Archivi

04-08: ‘Little Nemo in Slumberland’, Winsor McCay. 1907. Wiki/Public Domain

09: ‘Gasoline Alley’, Frank Oscar King. 1907. Wiki/Public Domain

11: Book cover of 'Delirious New York, Rem Koolhaas