“I am also happy to see that the office, even if it is called Clément Blanchet Architecture (at that time, in 2014, I did not find a better name), starts to be called C B A, reminding somehow the first three letters of reversed abecedaria, as a kind of the beginning of an approach, a methodology”, Clément Blanchet

“I am also happy to see that the office, even if it is called Clément Blanchet Architecture (at that time, in 2014, I did not find a better name), starts to be called C B A, reminding somehow the first three letters of reversed abecedaria, as a kind of the beginning of an approach, a methodology”, Clément BlanchetClément Blanchet, besides having his own firm, is a teacher and lecturer at various universities, a critic, actively involved in international events and conferences. He has also been recently appointed chief advisor for the metropolitan area of Annecy. Simplicity, clarity and unity appear to be the aim of his works, an architecture that sprouts from a complex examination of multiple interrelations and intends to achieve a real fulfillment through a dialogue with the elements constituting the surrounding. A building cannot exist as an isolated gesture, but must branch out its veins and know how to offer nourishment to the part of the city belonging to it. Very light and transparent expressions are constantly seeking interaction. Although they are extremely contemporary, they imply a long pause of silence, a profound process of reflection: the dilemma consists in finding a statement as less invasive as possible towards a pre-existing context. Interventions are not limited to sustainability dictated by current technology but search for a sustainability able to satisfy human and social aspirations.

During this period, due to the pandemic, especially initially, we have strongly felt the need to disconnect and interrupt the breathless rhythm that dominates our daily lives. Clément, despite his young age, has been supporting for some time now this need and he is used to recommend to his students that, once architects, it will be fundamental they acquire in planning a critical distance, impossible to be reached if not allowing themselves the calm to observe and digest, finally finding a more balanced and efficient voice. He likes to use medical terminology, thinking that architecture and medicine must share a certain methodology. There are exact analogies, such as when the doctor recommends to respect the slow process of digestion or to observe a period of convalescence, a certain slowness to regain health, and full recovery. He has very precise ideas, but loves to reach a conclusion in a somewhat Socratic way, avoiding drastic assertions and stimulating his interlocutor through apparent doubts and questions leading to the desired direction.

There is a concern that he often emphasizes, talking about, the fear of homologation. We are living in a century of megalomania during which architects, suffering from an originality syndrome, are unfortunately looking for acts that could arouse curiosity and make people talk, not caring, as they should, about helping society, that is the major priority. There are projects I haven't talked about, which belong to a smaller scale, although Clément does not like to identify his works according to the extension of a surface, believing that commitment and dedication to any design are the same. His small creations exude in fact accurate and great passion, revealing always different and extremely innovative approaches and paths.

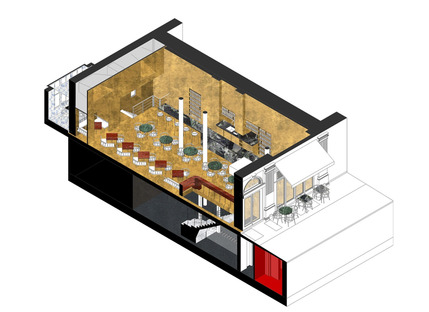

Grillé Restaruant, Paris, France. CBA.

There are many restaurants, a series of Grillé, in the most disparate areas of Paris, which face the challenge of unity in the diversity: they translate a new concept of fast food into the contemporary world, linked to a classic Turkish dish, the ‘kebab’, and convey the message each one with its own individuality and character, according to the different locations in the city. The culinary experience focuses on itself the architectural choices, causing a number of formal outcomes in respectful and harmonious consonance with the gastronomic menu. Marbles and brass celebrate, for example, the different temporalities, past, present and future, towards which is oriented The Chabanais, a restaurant located in the luxurious Mount Street of London. A variety of marbles promotes the variety of taste experiences while brass, with its patina of refined preciousness contributes to the particular, refined atmosphere, enhancing the culinary moment in its most sensual and hedonistic aspect.

Recent news gave CBA the opportunity to start the new year with ambitious and truly optimistic perspectives: they have been awarded the renovation of the legendary Bauer Stadium in Saint-Ouen-sur-Seine, France. The project, won in collaboration with SCAU, foresees a broad and complex program for this focal point of urban intersection and mythical historical site of one of the oldest Football clubs. A 40,000m² mixed-use development will transform the current stadium, flanked by a commercial park, embracing shops and activities dedicated to sport, fashion and restoration. This conductive space of meeting and collective life will live 365 days a year, rekindling the intensity and strength of the Fan Experience. Offices and restaurants with large terraces overlooking the field will allow everyone to participate from practically every corner during football matches and events. The intervention will certainly not disappoint and, satisfying a collective aspiration, will confer a new effervescence to this emblematic sports and social forum.

1—Why did you decide to do your initial practice in OMA’s studio, Rotterdam?

Infused by the Architectural Association in London, where I was studying, I was fascinated by Oswald Mathias Ungers, and one of my teacher was Madelon Vriesendorp. I actually discovered some of OMA first projects. I was ready… and in a probably naive way, I sent my portfolio to OMA, willing to explore the unknown. And after a long interview, I received an email that I should come for an internship the next day. It was supposed to last 6 months, it lasted 10 years. Together Madelon and I became friends, back then I was not aware she had married Rem.

2—Young people would certainly like to know what the experience in OMA’s studio was like, working more and more alongside Rem Koolhaas.

There is the Myth obviously at first. Then you quickly discover OMA as a place which offers you a chance to discover who you are. I was happy to manage a close and mutual respectful relationship with Rem.

At the end, once trust is there, some signs, drawings or texts translated on the fax machine allowed us to progress. The fax was a wonderful tool to digest reality as it proposed by itself a first understanding. It’s like if you received the script of the message.

3—Among the projects you carried out in that period, is there one in particular that gave you greater satisfaction and what are the reasons?

Recalling over more than 40 projects I was leading at OMA, it is difficult to answer. Each project is a journey, a set of memories, a way to draw, to represent, to think. It’s also about people, and interactions, and fun.

Yet, if I try to answer your question, I am guessing I was personally impressed to think I could design a bridge without knowing anything about actual infrastructural technics. In my little French “corner” of OMA France, located in a shared Parisian office, and after usual many options attempts to consider what a bridge should be, I desperately decided to simply do an insipid urban plate displayed above water. Probably I did so, because I could not think of any other design excuse. We were about to submit the competition and I remember I texted Rem to mention I am not sure about this one as I think we are submitting a non-design.

It’s fantastic to think that while I was developing this concept of a place to let uses happen on the Garonne without any “sign” of beauty, of any Architectural gesture, I could let myself think we could explore so many other fields. This bridge, later called Simone Veil, is kept to the simplest expression, the least technical, the least lyrical, in fact an almost primitive structural solution. The bridge is conceived not to be an event in the city but a place to promote the events in the city. I then could think to design a bridge is possible.

Bauer Stadium in Saint-Ouen-sur-Seine, France. CBA in collaboration with SCAU.

4—Did the 10 years of collaboration with OMA help you when you decided to create your own practice?

I wanted to promote spontaneity and experimentation again. I needed a new beginning somehow. When I started at OMA, we were about 40 architects and the family was recognizable, yet when I left, the office was above 300 employees. I felt the corporation was too big for me. We were spending more time in resolving and focusing on communication issues, than architecture.

After five years of receiving, and five years of giving; a balance was reached. This process offered me a chance to discover who I was. OMA is a machine to discover and decide who you are, can become, develop yourself.

5—Doing a final balance, and considering these 6 years that saw you involved in the new adventure of your practice: how did things go? Were the results above or below expectations?

I am happy to develop an office which is capable to observe the French cases as since we can diagnose and work on other architectural fields in Europe, Asia, America. The atelier is structured as a laboratory, it expands and recesses, discovers, observes, questions. I am also happy to see that the office, even if it is called Clément Blanchet Architecture (at that time, in 2014, I did not find a better name), starts to be called C B A, reminding somehow the first three letters of reversed abecedaria, as a kind of the beginning of an approach, a methodology.

I am observing that the office is also significant for other professions: literature, geographies, sociology, philosophy, economics. I think the office is in fact more than an observatory of Architecture and its boundaries. C B A is trying to generate excellence, freedom. We accept to fail in order to learn.

6—During our podcast we talked about how difficult it is to win, affirming an own identity, in an era dominated by homologation. However, you have shown that things not always go in this way, winning many competitions. How do you explain your success?

As an architect (if I am) I do believe you must fight homologation, and fight for new uses, and look for methodologies that question the images driven by the society. All is about images, while it should be about essences instead. It’s about being stronger and immune. To learn is about to fail. Competitions are good to exhaust ideas; I do believe adversity is a good teacher.

Mithridatism is the practice of protecting oneself against a poison by gradually self-administering various toxic products. This immunity is acquired by the repetitive and progressively increasing intake of these harmful substances. The process of creating requires possibly a certain type of Architectural Mithridatism. Enthusiasm and obstinacy need to be your qualities required firstly once you decide to do architecture.

7—To build, as you affirm, is an act not sustainable in itself: how do you try to be as less invasive as possible and as sustainable as possible in relation to a context?

In a world invaded by signs, incentives, gadgets, options, stories, architecture simply becomes composite, plastic, global, consensual, technological, dependent.

I am afraid that Architecture tries to only be sustainable by relying on new technologies. Technology is seen as an elixir of today’s challenges.

As indeed to build is not sustainable, we should question instead where should we reveal modern progress? How to reveal a local architectural action? Can we do architecture without robots, without glue, and think passive solutions? Can architecture stop being a “martyr” to modern and technological progress?

8—How do you think the world can be helped by architects in this near future?

The near future is driven towards a certain type of resistance. To simply generate progress in 2021's we should resist several phenomena: To resist nostalgia, to resist politics, to resist nature, to resist utopia, to resist egos, to resist beauty, to resist options, to resist consensus, to resist planning, to resist technologies, to resist graphics, to resist speed, to resist media, to resist publicity.

Architecture should generate a new sign of endurance, potentially the only option to reveal future sources of optimism. In 2021’s, Architecture should not always be extra ordinary. It should reconsider its ability to be ordinary within a new type of collectivism, source of an extra ordinary urbanism. Let's slowdown in 2021. Should we use the current crisis to frame conception, architecture? In this crisis context, what if architecture could help to reconsider a certain type of hope?

Virginia Cucchi

Credits:

Clément Blanchet Architecture, CBA: https://www.clementblanchet.com/

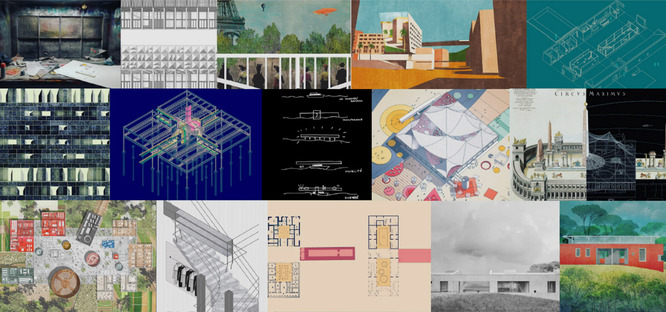

Cover: Concept drawings of Clément Blanchet Architects

1-3: Stadio Bauer, Saint-Ouen-sur-Seine, France. CBA collaboration with SCAU. Photo courtesy of CBA.

4-8: The Chabanais, Mount Street in London. CBA. Photo courtesy of CBA.

9-10: Grillé, Paris. CBA. Photo courtesy of CBA.

11-13: Le Dauphin, Paris. Clément Blanchet with Rem Koolhaas. Photo courtesy of CBA.