19-10-2021

RE-BIRTHS

BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group, X-Architects, James Corner Field Operations,

United Arab Emirates, Peccioli (PI), Italy, New York, USA, Copenhagen, Denmark,

waste-to-energy, landfills, waste,

Paused...

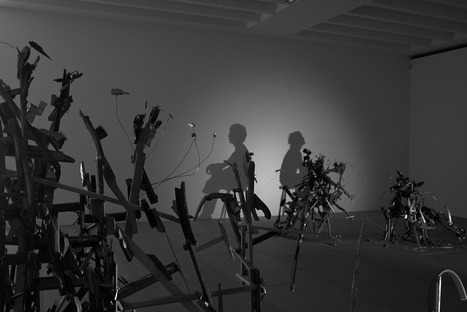

The trash stacks refer insistently to the 'disposable' mentality deeply rooted in today's consumer culture, to that enormous quantity of garbage daily produced and abandoned with just the same frequency and carelessness, but the continuity of the narration, playing on contrast, invites us to reflect on the possibility of a rebirth. The two often love to dwell on the concept of duplicity of opposites, alternating binary readings that feed on the most debated antithetical dualities in our society, such as the juxtaposition for example, between high culture and anti-culture, male and female, craft and rubbish . The artistic creation that can be generated from waste products is what I intend to talk about, that magical, alchemical process that transforms the ugly into beautiful, what has been condemned into something that strikes us for a newfound expressive shape and for a renewed capability to make us hope for authentic redemptions.

In this regard it’s exemplar what Peccioli, a small municipality in the Tuscan hinterland, was able to demonstrate already many years ago, around the end of the ‘90s, by taking with great courage a responsibility that its neighborhood unanimously rejected with obstinate hostility. The management of the landfill in the nearby village of Legoli, to which six municipalities referred for their waste disposal, was showing serious inefficiencies and was provoking concern about the environment. This complex situation pushed the municipal administration, led by the mayor Renzo Macelloni, to take a decision that could not be postponed, with the competent collaboration of experts who suggested a sanification plan and a treatment plant that made possible initiatives until that moment in Italy considered incompatible with similar contexts. It was 1997 when, with the consent of the citizens was formalised an agreement, the public-private company, Belvedere SpA divided shares between the municipality and the residents. The landfill was not, as it is normal trend, segregated or hidden, but rather became the field of growth of programs that, in their variegated multiplicity, encouraged the development of a real laboratory of ideas and experiments in constant ferment. By investing in the energy produced from recycle it was activated a chain of impulses that, among the skepticism of those who had firmly opposed the initiative, reached unexpected economic profits, over 300 million euros per year that fuelled and continue to support research, art and culture, fostering active sharing and social involvement. The biological mechanical treatment plant, periodically checked and updated, allows to combine the production by innovative biogas technology, partly used to supply electricity, with a rich agenda of interesting proposals, appointments, open-air meetings under the stars, able to provoke a vast response from both local and international audiences, making possible the protection of the territory in its integrity and its enhancement.

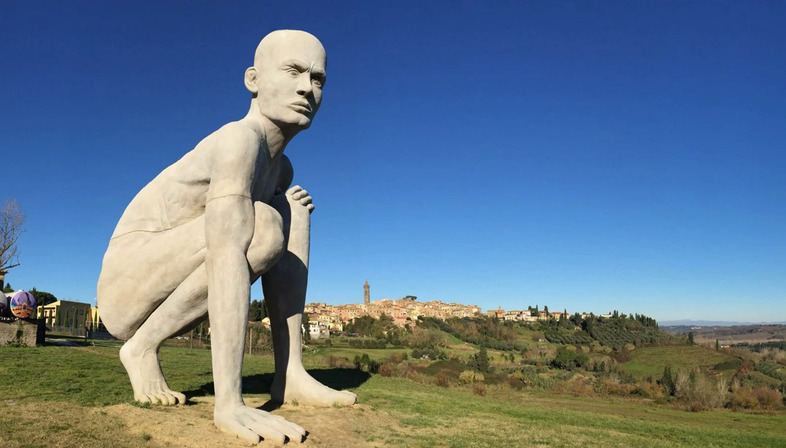

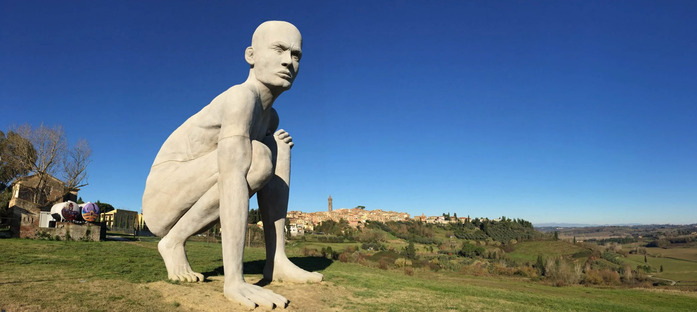

Gigantic, monolithic presences capture our attention with the magnetic and catalyzing force of their colossal dimensions and, in the act of emerging from the ground along the perimeter of the area, appear as the guardians of this spectacular futuristic scenery, a stage not delimited by borders that hosts classical music concerts, theatrical events and fashion shows, due to the presence of an amphitheater, as unexpected as seductive. The imaginative potential of contemporary art synthesizes and symbolically underlines the regenerative force of this 'Green Triangle', as it is usually called, with interventions that repeatedly punctuate the surface here and there, expanding and spreading with their impetuous innovative charge, even through the neighborhood. The vibrant notes of the landfill's colorful retaining wall, work of the English David Tremlett, famous for his murales around the world, radiate, reaching the medieval village. And many other important site-specific installations of Italian and international artists are following, rhythmically leading along the alleys of Peccioli, a small but very fascinating town, that is gradually conquering, with its aspiration to innovation and passion for beauty, the emulation of many other surrounding centers.

Technological innovation is one of the essential components that, thanks to a clean energy, has favoured and contributed to the success of this profitable bioeconomy, managed as a participatory operation to promote art and culture in defense of the territory, as an aid to the community and openness to the outside. This avant-garde technology, which has made possible to activate an experience that is imposing itself beyond national borders, from the landfill, following the widespread proliferation of art, invades the streets of the village with one of the first experiments in the world of social robotics, actively striving to fulfill everyday tasks, providing for the needs of those in difficulty. The force of rebirth of this engine of ferment and activity that devours tons of garbage and regurgitates as much power, nurtures the entire community with its positive impact. A story of waste generates a story of audacity and pragmatism, a truly virtuous narration that, through 'good practices', choices of sustainable initiatives, both ecological and participatory, has enriched the society by providing well-being and beauty. An example welcomed in the Italian Pavilion during the current edition of the International Venice Architecture Biennale as an exemplar model of ‘Resilient Community’, for its capability to transform a threat into an opportunity and to re-appropriate itself, thanks to a difficult and radical choice, a future based on eco-sustainability.

Among these examples of newfound health, there is another ongoing experiment that impresses us in the search for a healthy future in a megacity’s life. In 2030 we will have the pleasure to visit a park that will be the largest in over a century in New York, about three times the size of Central Park. Apart from its dimension, what makes it more special is its origin, that begins from the transformation of what was once the largest dump in the world. The park, thanks to design, engineering and ecological restoration, will emphasize with strong expressive characters, a rebirth in the name of environmental sustainability, symbolized by the repopulation of wild fauna and flora, a myriad of physical and recreational, cultural and artistic activities.

It was in 2001 that it stopped accepting garbage and following an international competition, the landscape architecture studio, James Corner Field Operations, assisted by experts who monitor the reclaimed land, started in 2008, the first part of the intervention, that foresees a time span of 30 years and is divided into three phases. Four gigantic hills, former heaps of trash, with tidal streams that cross the center of the landscape, constitute the topography that will animate a wide network of paths, recreational waterways, naturalistic excursions of an extremely interconnected park. What's even more incredible about the program is that “New York City,” as the New York Times points out, “set aside a parcel of land as big as Lower Manhattan south of 23rd Street— and just let it go to seed.”

Perhaps a necessary public act, because the project, at the conception, was not exactly an expression of true sustainability. Nature is healing along these 2,200 acres of the island's west coast closed to garbage for the first time and what is happening is visibly wonderful. Goats have been introduced for their ecological restoration capabilities and we read that flocks of birds are animating the renewed scenery, with large numbers of herons and bats, herds of animals along the paths and even, the red fox has been intercepted by hidden cameras playing at the edge of the growing woods. And the miracle does not seem to have reached its peak because the Foundation Freshkills Park Alliance, a non-profit organization that manages the park and finances it, emphasizes that the best is yet to come. When the park finally will open, it will be important to recall a wise warning from Robert Sullivan, passionate author of texts on the environment, defined by the New York Times Book Review "an urban Thoreau". Sullivan invites us to think about Freshkills not only in the terms of the unbelievable miracle of sustainability that has been operated but “we have to see it too as a reminder of what the city consumes — those mountains are made of our trash. And we have to remember what it means that the hills’ growth stopped.”

There is another interesting situation that sees two interventions concerted in the effort to rehabilitate a damaged ecosystem: the first, began in 2005, strived to cleanse and purify from the toxic chemicals an ancient chain of wetlands along the coast of the Emirate’s Arabian Persian Gulf, that had become a waste dumping ground, while the second is a gesture that architecture bestowed when, after years of passionate dedication, the entire area has been regenerated and was recovering the original wild, fascinating pristine context. Over 35,000 trees have been planted and 350 different species of birds have returned, without considering an area specifically studied to accommodate more than 30,000 migrant birds during their passage. In this frame of authentic, sensitive preservation, perfectly fits the intervention of equally respectful architects who have concentrated their efforts to find a compromise between the need to bring to attention ecological imperatives, educating for a more responsible future, and the sincere concern of keeping the guests invisible observers, extraneous to any possible disturbing action. This is how Wasit Wetland Center was conceived, inaugurated in 2015 harmoniously merged with this precious Nature Reserve and its ecosystem. A varied terrain, extending between sand dunes, salt lagoons or freshwater basins, guarantees food and survival for the rich wildlife.

Author of the design and collaborator in the masterplan is X-Architects, a firm from Dubai. Simplicity and respect influence a language that, adapting to the natural topography, is expressed through three slender parallelepipeds as extremely minimalist idioms. One of the long slats, sunk in the sand dunes, proposes an uninterrupted and discreet glass window that, slightly inclined, allows visitors to admire, without being perceived, the undisturbed birds in their natural habitat. It completes and intersects with the other linear elements, generating an interesting game of apparent ribs running and radiating along a surface of 200,000m2. The coveted recognition by the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2019 will underline the architectural excellence and deep ecological commitment of this collaborative project, the first in the United Arab Emirates to receive this prestigious honor.

I like to conclude by dedicating the finale to Denmark and its ‘green capital’, Copenhagen, that, talking about constructive ways of possible adaptations or transformations in the face of the epochal challenges that lie ahead, due to the effects of climate change, certainly deserve consideration for how they have been active for years in an attempt to respond positively, we can say in a resilient way, to the climate crisis and to constantly changing environmental scenarios. A decade ago Bjarke Ingels won an international competition, by proposing the idea of utilizing as ski slopes the steep pitched roof of a new waste-to-energy plant, CopenHill, 5 km from the city. The sophisticated engineering work, conducted by a multidisciplinary team of experts, made it possible that a structure, normally considered polluting, could perform a clean disposal action, seeing trees and bushes rise on its top, hiking trails, corners dedicated to play and fitness, climbing walls, an authentic natural, luxuriant and robust urban recreational park, in addition, to a ski slope of over 500 meters.

“A generous ‘green gift’ that will radically green-up the adjacent industrial area. Copenhill becomes the home for birds, bees, butterflies and flowers, creating a vibrant green pocket and forming a completely new urban ecosystem for the city of Copenhagen.”, says Rasmus Astrup, partner of SLA, a passionate laboratory of landscape design, that aims to find a mediation between nature and architecture. The group collaborated on the project, managing to solve demanding challenges and achieving this much admired and appreciated result.

Virginia Cucchi

Credits:

Cover: Peccioli, Fondazione Peccioli Arte, http://www.fondarte.peccioli.net/

01-03: Tim Noble & Sue Webster, Flickr, CC, foto di Lux & Jourik : http://www.timnobleandsuewebster.com/

04-13: Peccioli, Fondazione Peccioli Arte & Belvedere Spa: https://belvedere.peccioli.net/ | http://www.fondarte.peccioli.net/

14: Freshkills Landfill, Staten Island, New York, foto di Staten Island Museum Archives

15-18: Freshkills Landfill, Staten Island, New York, Flickr, CC, foto di James Dunham : https://freshkillspark.org/

19-29: Wasit Wetland Center, UAE, X Architects, Aga Khan Cemal Emden & Nelson Garrido : https://x-architects.com/

30-37: Copenhill, Copenhagen, BIG Architects, foto di Laurian Ghinitoiu, Aldo Amoretti, Rasmus Hjortshoj, and SLA : https://big.dk/#projects