03-07-2020

Ostana’s Mizoun de la Villo and the rebirth of a village

Antonio De Rossi, Luisella Dutto, Massimo Crotti,

Laura Cantarella,

Crotti, De Rossi and Dutto’s Mizoun de la Villo, meaning the “house” of La Villo, which is the central core of the Alpine settlement of Ostana, in the province of Cuneo, offers an opportunity to study the surprising history of a village that seemed fated to disappear but has now been brought back to life.

Ostana, a municipality consisting of a number of settlements scattered mid-way up the slopes at an elevation of 1100 to 1600 metres in the upper Po Valley, in Piedmont, has been a focus of attention for some time. In the mid-nineties the first articles were published about the rediscovery of a village that was reversing the process of abandonment so frequently seen in Italy’s mountain villages. The phenomenon lasted almost a century, for Ostana had a population of about 1200 in 1921, dropping to about 700 within the next decade and continuing to shrink over the years until the village was down to a population of only 6 elderly residents in the 1990s.

One of the principal causes of depopulation of these mountain valleys was mass migration toward the industrial city of Turin in the second half of the twentieth century: a historic shift which was in the end balanced by an inverse phenomenon when people began to go back to the village to save it from decay. There were two great drivers of this trend, one political and one architectural. Attention was drawn to Ostana by a movement focusing on appreciation of the landscape, which incorporates architectural and environmental qualities that have remained intact as the years have gone by. Unlike many places in the mountains, there has been no exploitation of the picturesque, no evocation of a lost world rediscovered as a cure for the ugliness of the big city, permitting any form of imitation provided it brings in a profit.

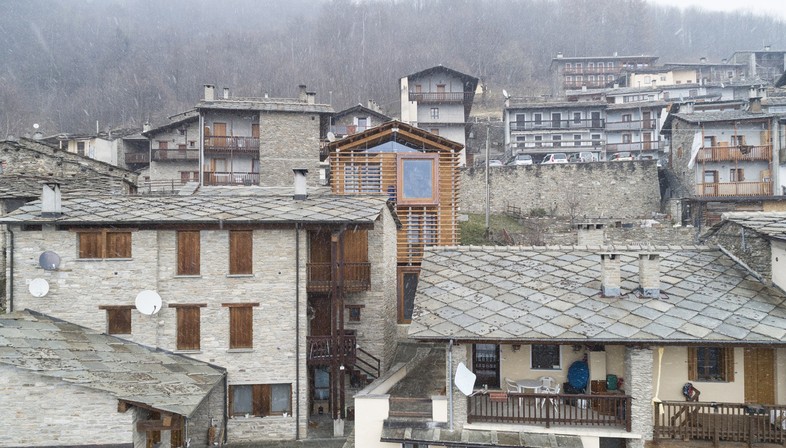

Ostana’s strategy, instead, has relied on preservation of the authenticity of the place in order to start new projects, whether entrepreneurial, social or cultural. With the support of the local government, in the 80s and 90s architect Renato Maurino, who had always lived in these mountains, drew up a manual of architectural principles defining local building traditions as well as compositional innovations introduced by the best architects who have worked in the Alps, centring around use of local materials such as stone and wood. From that time on, all redeveloped buildings were renovated making reference to this architectural vocabulary, making Ostana a unique example of safeguarding a landscape which is not frozen in time as an end in itself, but continually regenerating and growing. Thanks to skilful implementation of this inspiration at the political level, the village has seen plenty of new interest and new partners, promoting cultural initiatives in the fields of literature, cinema and ethnography which have led to the second phase in the programme, aimed at creating new opportunities for settlement and growth in the area.

Another milestone was the start of the local government’s partnership with Politecnico di Torino, and specifically with professors and architects Antonio De Rossi and Massimo Crotti, to implement a series of projects promoting sustainable tourism and culture, some of which were based on reclamation of the structural use of stone. In 2011 the partnership led to creation of a “Manual of guidelines and technical orientation for reclamation projects and new constructions in Ostana”, and a number of historic buildings were renovated with quality architecture, so that Ostana is often described as a “laboratory of Alpine architecture”. Surprisingly, in recent years the village’s population has grown to about fifty people, and they are not all old, but, as Antonio De Rossi reports, many of the newcomers fall into the 20 to 40 age bracket, with a high level of education, and operate their own businesses or are employed in entirely new sectors such as culture, tourism, architectural reclamation, and new forms of agriculture; many of them have children born in the area. This recreated social, economic and cultural fabric of relationships and partnerships is founded on love of the place and, we might add, pride at having succeeded in implementation of a solid, successfully, constantly changing community project.

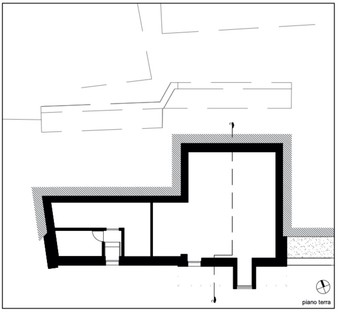

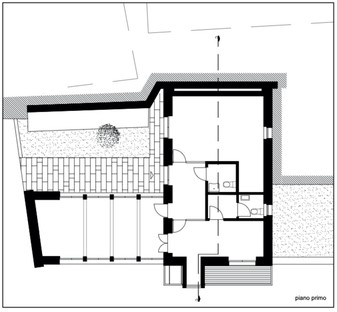

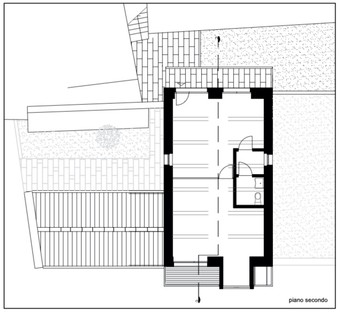

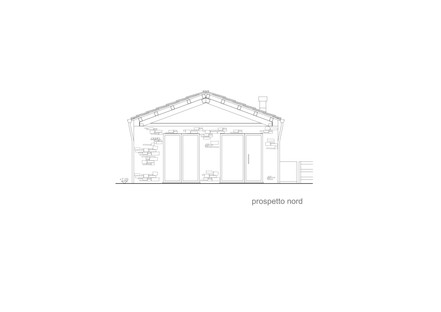

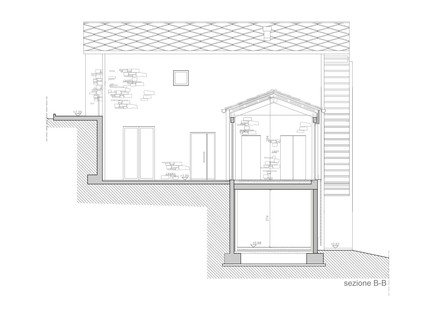

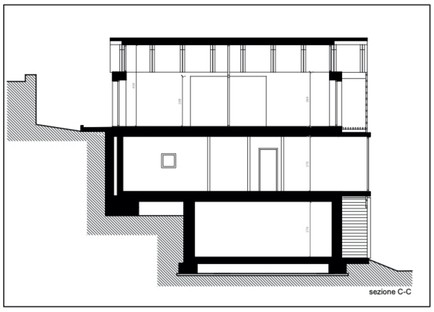

With funding from the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport’s 6000 Campanili Programme, in 2015 the local government commissioned Crotti, De Rossi and Dutto to build a new community welfare facility combining a number of services: a public medical clinic, a bread- and pastry-making workshop, a library and wellness facilities. The project is built with an L-shaped floor plan joining back together a portion of La Villo where old buildings had been lying in ruin for years. The new complex takes advantage of the differences in elevation due to the mountain slope and is constructed on three levels with three entrances serving the various different activities contained in the centre. The interior establishes links and connections, and to the northwest is a little patio or plaza providing access to the first and main level. The two volumes forming the L are based on the two main morphotypes of Alpine architecture, which, as Antonio De Rossi points out, Edoardo Geller identified in his reflections: “the casa a rittochino, a house with its ridge building along the line of maximum slope, and the casa a cavalcapoggio, built with its ridge parallel to the contour lines.”

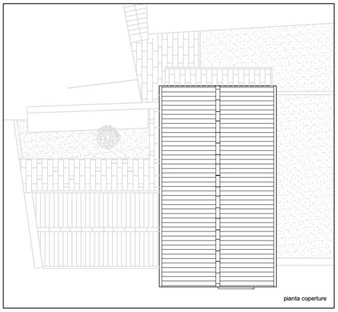

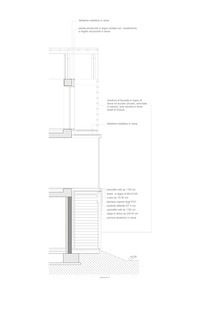

The walls are made of stones of different sizes and shapes, with a special focus on the three-dimensionality of surface coverings; the roof structures incorporate glulam trusses and the window and door frames are also made of wood; the roofs are covered with square stone tiles.

The main façade, facing south and made entirely of timber, is designed exclusively on the basis of existing types of construction element constituting “lobbie”, the most ancient mediating elements in traditional mountain architecture, described as extensions of one of the pitches of the roof through beams at the thrust-bearing walls, supported by pillars. The details of the project included balconies and bow windows with sunbreaks alternating on different levels, giving the building an unusual “face” and a variety of different views of Monviso. The new depth of the façade offers a different angle of light in the single sleeve. This innovation is achieved using traditional materials, larch wood and galvanised steel, proposing a recognisable, respectful change.

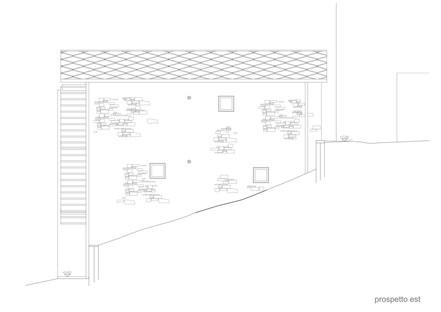

The eastern wall, made entirely of stone, has three new small windows framed with corten steel, ensuring proper lighting and ventilation for the additional utility areas inside.

The stone structure at the end of the secondary volume is completed with horizontally laid larch infill and glass, reflecting the look of a barn or filled-in loggia.

Use of timber and metal on such a vast scale is motivated partly by the latest new criteria of sustainability and energy conservation, as they are recyclable materials producing constructions which are reversible in that they are based on dry assembly. As the manual states, increased use of timber in construction can contribute to the development of a short supply chain with local production in the valley. And in terms of energy efficiency, Mizoun de la Villo is set up in a network with the Sports and Wellness Centre below it, sharing the same geothermal, photovoltaic and thermal solar energy sources.

We may definitely conclude by affirming that Crotti, De Rossi and Dutti have created a community centre that keeps alive the memory of the buildings of the past, reflecting the “textures” of historic buildings in their choice of materials, relationship with the sloping land, spatial dimensions, ratio of solids to hollows, and layout of indoor and outdoor space. Without ever falling into the trap of imitating elements of traditional styles for the sake of tourism, the complex fits perfectly into the process of regeneration of the village of Ostana, offering a potential example for many more villages in Italy’s mountainous areas.

Mara Corradi

Architects: Massimo Crotti, Antonio De Rossi, Luisella Dutto

Client: Municipality of Ostana, Cuneo, Italy

Structures and installations: Fabio Bertorello, Aldo Baronetto

Builder: Impresa Farm di Rabbone & c., Savigliano

Funding: 6000 Campanili Programme, Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport

Cost: € 425,000

Gross usable surface area: 290 sqm

Completion: 2019

Photography: © Laura Cantarella