15-07-2020

WOMEN AND ARCHITECTURE

Women in Architecture ,

"Female architects" seems to be an unshakeable phrase.

"Female architects" seems to be an unshakeable phrase.The problem of a female presence not being recognized in the same way as the male counterpart has been debated for quite a long time and, although progress has been made and several achievements reached, there is still a long way to go before arriving to a situation that could satisfy those who today have been so penalized and even marginalized. In an article of 2016 in Huffington Post, the discussion was centered on how a greater balance of shared responsibilities and initiatives would be extremely important for the Institution, benefitting and enriching the dialogue between both categories, beside satisfying the unquestionable moral imperative, which claims equal rights for all members. A similar form of obstructionism has also occurred in the scientific field and women have been obliged to strive hard to see their efforts recognized. We live in a society that has always imposed roles, relegating them to the orbit of the family and the care of children, while man engaged in the world of work. It has come at a great cost to get rid of this form of stigmatization, and when women have tried to find their visibility and enter into historically male-dominated 'arenas', not obeying to the limits imposed by an ancestral tradition, have been highly contested or strongly opposed.

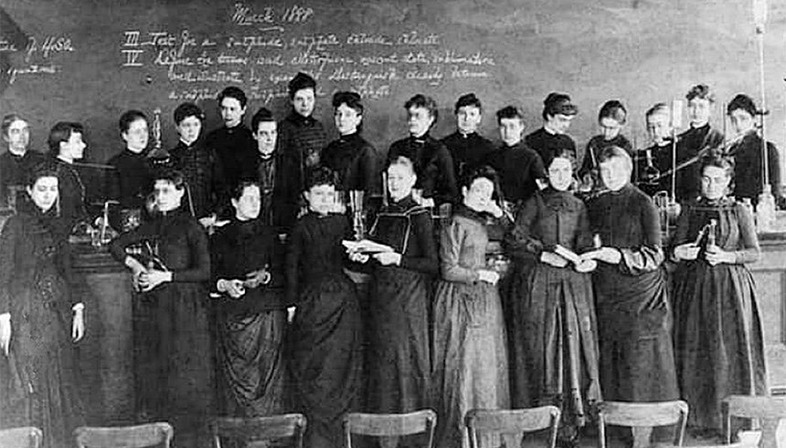

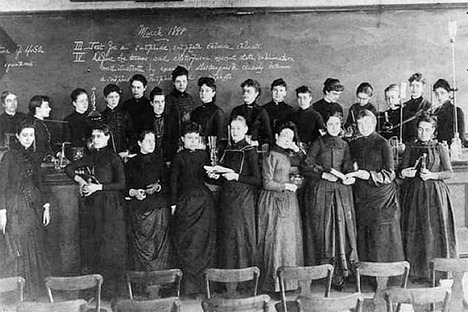

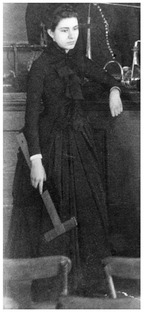

There are women who have suffered so much bitterness that they decided to abandon the profession of architect, even if loving it very much, failing to find the strength to react to such a hostile and discriminating reality. Sophia Hayden, won the competition for the World's Columbian Exposition, with the execution of the Woman Building, but she had to undergo the frustration for the all harassment inflicted on her, during and after the two years of construction, finding herself, at the end, with a nervous breakdown. She managed to overcome the difficult period, but with this weakness, she unfortunately confirmed the widespread idea that architecture was not suitable for the female. If women had realized, and had been more aware of the unstoppable jealousy their abilities often triggered, they would probably not have been let down by a world so hostile and difficult, rather they could have predominated, without renouncing their passion.

Sophia Bennett Hayden at MIT in 1888/source image MIT Museum/Wiki

Eileen Gray, highly praised and encouraged by Le Corbusier, and Jean Badovici, with whom she had a relationship for a period of time, to dedicate herself to architecture, and not only to interiors, a sector in which she had already been very successful, entering into elite circles of Paris, designed with her lover, critic and architect, who nevertheless played a decidedly irrelevant role, the famous seaside villa in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. The furniture conceived with avant-garde criteria included some of Eileen's most iconic pieces and also some of her more experimental creations. Le Corbusier was so dazzled that he was somewhat obsessed with it. When he photographed himself naked in front of eight huge paintings that he depicted on the white immaculate walls, with an intent to violate their purity and to insult Eileen, who at that time divorced from Badovici and had moved away from the property, alluding to her bisexuality, with this decidedly absurd act he demonstrated very well, even if emblematically, a desire for revenge for what he would have liked to accomplish himself. What saddens is that Gray, although very close to her father who, as an artist, had grown her with a very open and unconventional mentality, was so deeply offended that she unfortunately left little by little a world that belonged to her by right.

However, there are also successful stories of other pioneers who attest extremely strong-willed characters, personalities that made them real legends. Many have dedicated an entire existence to the achievement of an ideal, at the expense of their own private life, even if many are the examples of denied recognitions, marginalization, injustices, even misappropriation of their contributions and ideas from colleagues, if not by their, sometimes important, partners. However, they have proved, despite the reprehensible and repeated denigrating attempts and ostracism towards them, to be able to do excellent things. Among the many precedents that now we disdain so much but then practically passed in silence, I would mention a woman who perhaps for the first time caused a reaction of admiration and respect for all her efforts and merits, I’m referring to Denise Scott Brown. When in 1991, Robert Venturi, her partner in life, was awarded the Pritzker Prize, the dissent was widespread and publicly externalized with a huge number of signatures that required the correction of the attribution. It was necessary, in the opinion of many, to share the prestigious recognition with a woman of great value, who, in addition to having influenced a new way of seeing modernism, had worked alongside her husband in drafting a book on the design of the 20th century, which has become a fundamental reference for architecture. This 'fearless feminist icon’, as she has been called, for her verbal controversies with famous colleagues like Philip Johnson and the critic and historian Kenneth Frampton, will work on the success of the office she founded with her husband, but will finally declare with bitterness during an interview: “It’s hard for both of us — but particularly for me because I get obliterated. Visitors to our office have tunnel vision toward Bob. I am seen as his assistant, not a professional in my own right, and certainly not a designer. Why that’s anathema would take a book to define. In practice, I have my own work, my own identity, but mostly we work together, capping each others ideas so that it’s difficult to separate our individual contributions”.

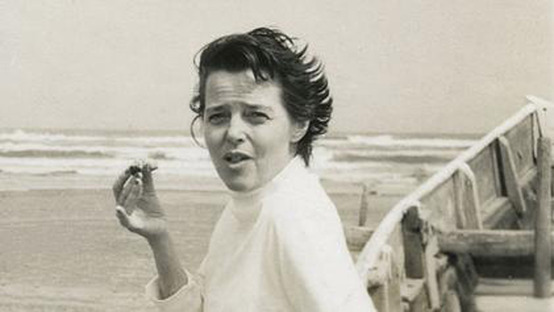

Denis Scott Brown by © Robert Venturi/ image courtesy of Lisbon Architecture Triennale

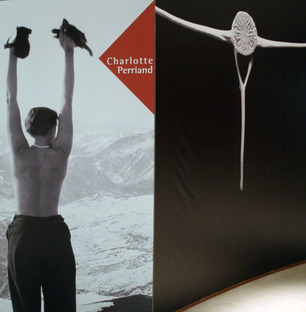

On the similar note, talking about an invisibility very often desired and fueled by the professional jealousy of those who feared the talent of a collaborator, the list of those who have been victims, is definitely very nourished. For example, we can remember Marion Mahony Griffin, who, despite having worked for Frank Lloyd Wright for 14 years, never had the pleasure of seeing recognized the merit for the development of the Prairie style or any accreditation for her watercolor renderings, which over time have become synonymous with Wright's work. Only with the passing of years she will have her revenge, winning the urban plan of the new Australian capital, Canberra. Half a century later, Charlotte Perriand, who graduated in furniture design in Paris, will face a decidedly humiliating offense from someone she particularly admired for his writings and criticism of decorative arts. It will be Le Corbusier himself that, when she showed up at his studio in search for a job, thinking she could follow the design of the low cost housing, replied with the clear intention of not recognizing the value of her specialization: "here we don't embroider cushions". It will be only after she became successful with her works displayed at the Salon d'Automne that the architect, who initially rejected her, will offer her a permanent job and the task of following interiors and furniture line. At the end of a single year she had already created three of the most famous chairs of the studio's production. Her extremely personal style, able to combine expensive chrome with wood, a traditional material, more affordable, arouse great interest in Japan, where she was invited and offered a particularly prestigious assignment at the Ministry of Commerce and Industry. Also in this case, the wound caused by the arrogance of such a contemptuous attitude will fortunately be soothed and completely healed by the great satisfactions of her achievements.

Examples of these and many other colleagues, who have been able to succeed on a path full of difficulties, should help the new generation of young women, instilling in them the confidence to fulfill results to be proud of. Too often it has been noticed that women have not felt to deserve the merit based on their talent and hard work, blaming and placing themselves at an inferior condition, not objectively judging those of their male counterpart who have reached success, not for a real meritocracy but for a great strategic ability of promoting publicly themselves with strong connections. "Women are always told: ‘You won't make it, it's too difficult, you can't do it, you can't participate in this competition, you will never win it’ , they need confidence in themselves and in the people around to help them climb”, says Zaha Hadid, who has always been proud to be “an architect, not just a female architect.” With her proud and resolute, practically indomitable character, she held a moment of fundamental importance for the birth of women awareness that perhaps lacked. Although refusing to be assumed as a symbol of a world that is gradually enriching itself with the contribution of women, Hadid has proven to be above those schemes and canons that provided a very different professional figure from the point of view of the aesthetic aspect, the color of the skin and in the behavior. She was one who never let herself be discouraged by the sometimes unflattering comments, and, not paying attention to those who accused her of being too rough and direct, she achieved results and left testimonials difficult to match, considering that, at the age when she passed away, very few express themselves with a similar resonance.

Going back to that long part of history, when to women with an innovative mindset were not given the chance to manifest their revolutionary visions and to carry out projects that would have been avant-garde, there had been a tendency to assign types and categories of buildings by gender. We continue to witness the widespread stereotype, triggered by the media and certain commercial advertisement, that the 'strong' men are normally responsible for designing buildings that impose themselves by height and by a powerful impact of expression. The stadium, the 30-storey tower, a hospital are normally assigned to men, the fashion boutique, the finishing touches for the beach house or the countryside cottage to women. Almost as femininity reflects itself in architecture with more delicacy and without that force that many women have been able to express and that is certainly not the unique prerogative of masculinity. Recently a colleague in admiration for SESC Pompéia, the amazing work of Lina Bo Bardi, thought to praise her with these words: “It's all so incredibly raw and ultra-brutal that you almost can't believe it's the work of a woman”. A compliment which certainly did not want to allude to difference of competences of the two categories but reflects a certain rhetoric perpetrated over time. Insisting on these tracks, either functional or linguistic, is not useful for anyone, we should rather arrive to a form of compromise that foresees a type of synergistic collaboration and allows these tracks, which run parallel, to converge towards the achievement of a common goal. All these excesses that emphasize differences should not always be used in a polemical and negative tone but should reach a completion which is nothing but the fruit of different resources.

Casa de Vidro, São Paulo, with Lina Bo Bardi, 1949-1951 © Arquivo ILBPMB, (Exhibition: Lina Bo Bardi 100 - Brazil’s Alternative Path to Modernism, Pinakothek der Moderne)

Mutual support is probably hard but there are women who have given an example of completion and enrichment alongside their male partner, who in return have had their help. These were relationships affective, healthy from a professional point of view, where the partner was esteemed and considered an active collaborator, not exploited as we have often seen happen. It is undeniable that there are gaps to be bridged, that it is difficult for women to reconcile the profession with the duties of mother and wife, but those who embark on a career, nurturing the ambition to pursue outcomes that have a certain importance, must work with the conscious choice, of knowing that they will face sacrifices, and without counting on fixed working hours or other forms of facilitation. The female presence at the top of strongholds traditionally dominated by male hegemony is increasingly more numerous and today their merits widely recognized. It is very significant that this year the Pritzker Prize was won by the couple Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara, Grafton Architects, and it is equally significant that both were awarded, attesting to the importance that in an increasingly fierce and competitive working world, play the complicity and solidarity between collaborators. It was also nice the reason of the award, that was not only determined by the value of their work, but also by the ethics they demonstrated in their practice, respecting and seeking cooperation with other colleagues. Their ability to implement particularly important values, equally difficult to safeguard, such as craftsmanship and the cultural connection with each place and context, which in their projects they continued to investigate time after time, is another point that has been widely emphasized and praised as an emulation model.

At this point I would like to conclude with the words of a woman I consider particularly gifted and intelligent, Elizabeth Diller, who, when asked how she would like to describe herself, replied that she likes to feel and to be an artist and an architect without having to mention that she is a woman. An example that ennobles the sense of freedom: having never had the slightest doubt to be able to reach anything she wanted, it is with great stubbornness that she devoted herself to what she considered indispensable. Having achieved success and power, she was finally able to create, alongside the man with whom she has always worked together from the times of university, the subversive and impactful architecture she had in mind, an architecture that provokes absolutely unscheduled experiences, involving with great participation the public.

Virginia Cucchi

Credits:

Sophia Hayden:

1-image: Sophia Bennett Hayden at MIT in 1888/source image MIT Museum/Wiki

2-image: Sophia Bennett Hayden at MIT in 1888/source image MIT Museum/Wiki

Eileen Gray:

3-image: Portraits of Eileen Gray/source image Wiki

Dennis Scott Brown:

Archive: cover : photo of Denis Scott Brown by © Robert Venturi/ image courtesy of Lisbon Architecture Triennale

Archive: 14-image Denis Scott Brown/ Agriculture and Architecture: Taking the Country’s Side/ image courtesy of Lisbon Architecture Triennale

Charlotte Perriand:

4-image: Charlotte Perriand in Japen, 1954 /source image Charlotte Perriand/Wiki

5-image: Charlotte Perriand in the Studio ph Robert Doisneau/source image CC

6-image: Charlotte Perriand Exhibition image source from Knowtex/Flickr

Marion Mahony Griffin:

7-image: Portrait of Marion Mahony Griffin, 1915/source: National Library of Australia

Lina Bo Bardi:

Archive: 8- Images courtesy of Fondazione Maxxi (Exhibition: "Lina Bo Bardi in Italy/ What I wanted was to have History")

Archive: 9- Casa de Vidro, São Paulo, con Lina Bo Bardi, 1949-1951 © Arquivo ILBPMB, ( Exhibition: Lina Bo Bardi 100 - Brazil’s Alternative Path to Modernism, Pinakothek der Moderne)

Archive:10- Images courtesy of Fondazione Maxxi (Exhibition: "Lina Bo Bardi in Italy/ What I wanted was to have History")

Archive:11- Images courtesy of Fondazione Maxxi (Exhibition: "Lina Bo Bardi in Italy/ What I wanted was to have History")

Archive:12- Portrait of Lina Bo Bardi/ Courtesy of Design Museum Gent ( Exhibition: Lina Bo Bardi - Giancarlo Palanti)

Archive:13- Portrait of Lina Bo Bardi/ Courtesy of Design Museum Gent ( Exhibition: Lina Bo Bardi - Giancarlo Palanti)

Gae Aulenti:

Archive:15- Portrait of Gae Aulenti/ Images courtesy of Archivio Gae Aulenti and Vitra Design Museum (Exhibition on going: Gae Aulenti: A Creative Universe)