16-02-2021

BRUCE ALONZO GOFF

Bruce Goff,

Anthony V. Thompson, Michael Stano, Rachel Cole,

Aurora, Illinois, Norman, Oklahoma,

He was only twelve years old when his father, after returning home, found him as usual designing flamboyant towers. He rolled up the drawings, made him put on a coat, stopped a taxi driver along the road, and asked to be accompanied to the best architectural firm in the city. The help of his father proved to be fundamental, as Bruce will declare in the following years. Arriving upon the office of Rush, Endacott and Rush, displaying the sketches, the reaction was really positive: the partners, and in particular AW Rush, with a determined, bold character, that could recall that of Theodore Roosevelt, impressed by the talent of the boy, immediately offered to him the opportunity of an apprenticeship. They promised the young man to teach him the profession, in return, they requested commitment and hard work to earn the acknowledgment of architect. By the age of 15, he was designing important houses and commercial projects, by 25, he was appointed as Partner. AW Rush, who was President of the company, although retired at that time, followed Bruce's progress, sensing the originality of his works, but also felt a need to protect him, warning of how difficult his life would have been due to his predisposition: "as long as you are in the trenches with everyone else, doing what they are doing, nobody will notice you or laugh at you. It's when you get in no-man's land that they start shooting at you from both directions and son, the way you are heading, you had better get a good tough hide, because you are going to be in no-man's land all your life.”

He was only twelve years old when his father, after returning home, found him as usual designing flamboyant towers. He rolled up the drawings, made him put on a coat, stopped a taxi driver along the road, and asked to be accompanied to the best architectural firm in the city. The help of his father proved to be fundamental, as Bruce will declare in the following years. Arriving upon the office of Rush, Endacott and Rush, displaying the sketches, the reaction was really positive: the partners, and in particular AW Rush, with a determined, bold character, that could recall that of Theodore Roosevelt, impressed by the talent of the boy, immediately offered to him the opportunity of an apprenticeship. They promised the young man to teach him the profession, in return, they requested commitment and hard work to earn the acknowledgment of architect. By the age of 15, he was designing important houses and commercial projects, by 25, he was appointed as Partner. AW Rush, who was President of the company, although retired at that time, followed Bruce's progress, sensing the originality of his works, but also felt a need to protect him, warning of how difficult his life would have been due to his predisposition: "as long as you are in the trenches with everyone else, doing what they are doing, nobody will notice you or laugh at you. It's when you get in no-man's land that they start shooting at you from both directions and son, the way you are heading, you had better get a good tough hide, because you are going to be in no-man's land all your life.”

The series of consequences that had led to the economic prosperity of the United States in the last decade of the nineteenth century, do not reflect Golf’s ideals, who considered the awareness of one's roots indispensable for a true architecture. He had a clear idea on the role that an architect had to play, free from any pressure or conditioning, and what was happening during the period was certainly far from his aspirations. The widespread tendency to exhibit a new social status, conferred by the accumulated wealth, had largely involved the architects of the time, who did not hesitate to indulge their clients' desire for ostentation and prestige. Palaces, one after another began to arise, recalling with their facades disparate fashions and styles of the splendid phases in the history of European architecture. A real madness, aggravated by the use of materials from the most distant and unexpected locations. An eclecticism solely dictated by money, far from that spontaneous intelligent and cultured game of Goff. Unfortunately, architects for the most part had chosen servitude to economic interests rather than favoring, as they should, references of place, time, local culture and tradition. In this 'cultural desert', which was mirrored in a form of empty standardization, there were naturally exceptions, that opposed the fashion of a 'Facade Architecture', advancing innovative functional and formal proposals, such as Richardson, Sullivan and adherents of the 'Chicago School’. Attempts that endeavored to promote native architecture.

Bruce Goff and Frank Lloyd Wright, Courtesy of Goff Archive, Ryerson & Burnham Archives, The Art Institute of Chicago; digital file@The Art Institute of Chicago

Bruce's father was the youngest of seven children and, once married, he began traveling from Alton, Kansas to Denver, Colorado in hopes of securing a better future for his wife and two children with his skills as a watch repairman. Unfortunately, work remained so scarce that he was forced to close his shop and, willing to accept any possible jobs, he decided to relocate to Tulsa, one of the largest and most prosperous cities in Oklahoma. It will be among other three locations in the state that little Bruce will spend the early years of his childhood, growing up on the outskirts, playing on farmland in the countryside and living in tiny houses: there will be one in particular consisting of a 12 x 24 ft room, where he will remember that food was so little that they went to bed often hungry. There was an electrifying summer with his sister in Kansas, in the small country residence of his great-grandmother, a self-taught painter, whom he adored. Infatuated by her collection of crystals, shells and other strange objects picked up during their walks, by her paintings of landscapes, and his great grandfather's small portraits of birds, flowers and fruits, he will become an enthusiast of nature. With practically non-existing personal belongings, everything reduced to the essentials, a deep respect grew in him for the conservation of simple and ordinary objects. He collected everything he found in the garden: stones, bones, sticks, leaves, calling them 'natural legos', adapting them as interlocking pieces in extraordinary games or creations. Despite having lived in mid-America, the mass culture and art of the time had no influence on him, on the contrary, he considered them too banal, full of clichés and stereotypes. Instead, there was a journey with his family across the vast plains of West America that led him to a brief encounter with the Native American Indians, the Cherokees, that left an indelible mark on him, still a teenager. What surprised him deeply was how the population endured the hard difficulties and burdens of an existence, which he could well-relate too, making it appear more bearable and less bitter. It seemed as if they had found an antidote, not to exorcise the limitation of their resources but to celebrate this poverty between colors and elegance, hand-made with dedication and passion artistic objects and garments to wear, adorned with beaded necklaces, feathered headdresses, knitted blankets and leather moccasins. A way to sublimate how to be satisfied with little or nothing, a real life lesson that will become a source of inspiration for him both in his daily conduct and in the realization of his works.

After several journeys, the return to Tulsa in 1915 will be definitive. The new wealth acquired by oil had caused a parallel desire for cultural development and activities. There was an atmosphere praising ‘nothing was impossible', something that will imprint Bruce's entire life. Here, he attended the sixth grade, before ending the school to work for Rush, Endacott and Rush. Helped by a teacher, he discovered a predisposition for arts: extremely gifted, he will produce a large quantity of exquisite drawings and paintings on any available surface he could find, leftover wallpaper, wrappers, newspapers, unable to afford a sketchbook. Painting, creating mosaics and working with applied arts will remain, together with long walks, his favorite pastimes, just as music. Classical music, in particular, will exert great involvement, with a strong attraction for Debussy's compositions, passionately following not only his symphonies but the man as a true teacher of life. One of the quotes, he adopted, that will guide his attitude both in his personal relationships and at work, recommended: "Give ear to no man's counsel, but listen to the wind which tells in passing the history of the world". His 'disobedient buildings' don’t use an orthodox vocabulary, neither adapt to a codified language, but rather subversive for their time, were very often misunderstood; there was no possibility of judging them without the extremism of a non-objectivity, considering them either excessively futuristic or excessively trivial.

There was another episode that with the great composer's recommendation will shape his almost impassive behavior in the face of the most offensive criticisms. In the past, his sister, who had a completely different character, annoyed at staying long quiet afternoons at home, would often provoke Bruce who didn’t indulge in her desire to spend more time outdoors with other children. Bruce remembers that, one day when yet another spite occurred, a glass of water deliberately spilled on a watercolor he had just finished, an act that would normally have infuriated him, he decided to pretend nothing happened. This apparent indifference had inexplicably discouraged her and put an end to the series of hateful acts. He was so pleased with what he achieved, that he decided he would always adopt this tactic with anyone in the future who tried to offend him. And in fact he was able to maintain this very tolerant demeanor, apparently careless, with those who didn’t understand or appreciate his creations. There are anecdotes about his imperturbable serenity even when the offenses were stinging, as in the case of Mies van der Rohe, who had pointed out that there was no need to invent a new style every Monday morning. If he had been present when Charles Jencks called him the 'Michelangelo of kitsch' he would surely have replied that his buildings rewarded, arousing interest.

In the art world, I would say, it is quite normal for those who are successful to assume authoritative and even somewhat arrogant attitudes, surrounding themselves with an aura that makes them appear as unique as possible. Instead, Goff never tried to stage any extravagant behaviors and the only note that could perhaps suit the eccentricity of his architectural style was his clothing, with a predilection for bright colors in contrasting combinations, particularly flamboyant for a conservative environment like the one of Oklahoma. He was able, relying on his unique strength, self-taught, without ever earning a degree, to obtain important awards, a position as teacher and subsequently the title of President of the Department of Architecture of the University of Oklahoma. And the contribution in the eight years of his mandate in the academic world is certainly understood more today than before. He succeeded in recruiting new teachers to transform the architecture education in a really revolutionary way, not based on those dogmas preached, but free from any programmatic or usual reference points. This is attested by an exhibition recently dedicated to him, that entitled "Renegades: Bruce Goff and the American School of Architecture", seems to want to apologize for those who did not recognize the merits rightly reserved for him. Goff, knew that many colleagues did not appreciate his work, yet he was aware of his own singularity, as well as, that innovation was not welcomed as it should. This led him to keep his courteous and jovial manners with all, not to feel a grudge even towards his most bitter denigrators.

As an architect, he always tried to build houses that reflected the identity and personality of their inhabitants, never resembling one another, suitable for an individual lifestyle and expression, a need dictated by his eclectic character. Dynamic geometric bodies and radical shapes, conceived with locally found materials, often recycled or reused, industrial waste, natural elements - goose feathers, coal, glass ashtrays and marbles - elaborated together in a bizarre and absolutely unexpected way, expressed his fantastic ingenuity. Anticipator of an era to come, an authentic precursor of a circular design, he would use large amount of waste, parts of dismantled serial productions, never rejecting anything that would help him to conceive a second life, crafting them as an integral component of every creation: a signature gesture that combined decorative and structural factors as an indissoluble whole. With courage and conviction he pursued the dream of promoting local and vernacular architecture linked to his egalitarian belief, accessible to anyone, but at the same time distinguishable, conferring to his dwellings a modern, unique, sartorial interpretation. His experimental optimism borders on an almost utopian vision of existence in syncretism with nature, and his production went beyond the expectations of a type of life connected to a certain status quo, concerned with providing a glimpse of a totally different way to live. Gifted with an inexhaustible vein, he never ceased to amaze with proposals that combined extravagance and a special emphasis on decoration detail or on the virtuosity of craftsmanship, aspiring that in every home people would have a space to be themselves. 'Common places of the heart’, far from the temporary superficiality of conventional fashions and symbolisms.

Ford House, 1949, in Aurora, Illinois. Designed by Bruce Goff. Photograph courtesy of Rachel Cole.

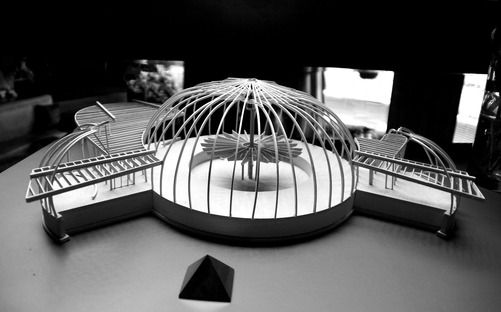

The opportunity to have known and applied cutting-edge technologies during his military service helped him to incorporate these engineering qualities into his work. When in 1949, he was commissioned the Ford House, in Aurora, Illinois, he resorted to an unusual radial configuration of the Quonset ribs in bright red color, arranged in rotation around the center of the plan, tilted to give a sort of bulbous, mushroom shape. The central circular hall measures 50 feet in diameter, inspired by the theory that the circle is "an informal, intimate and friendly form." Conceived as an area for family leisure or to host the company of guests, with no dividing walls or hierarchy of elements, flooded with natural light from a full-height glass facade and a skylight on the top, that open the space towards the surrounding without interruption of continuity, breaking the boundaries of interior and exterior. The spherical room is outlined by a curved wall in anthracite charcoal, studded with a refined patchwork of marbles and rough chunks of aquamarine broken glass, hardened waste thrown away from a glass furnance, to infuse the simple pitch-black bricks a sense of preciousness and richness. A thick woven hemp of ropes covers the ceiling of the entrance, juxtaposing the ‘herringbone’ motif, created by the diagonal arrangement of the cypress wood slats, fixed along the internal 166-foot dome. Each customized piece of furniture or decorative embellishment has the peculiarity of offering physical comfort while providing visual emotion. The house is composed by twelve different assortments of materials, applied and recontextualized in most inexhaustible and playful way, to produce spectacular sequences of the most unbridled and unpredictable aesthetics. To embrace the bold presence, two smaller domes on both the adjacent wings, reserved for more private areas, bedrooms and bathrooms, adorn its sides. Bruce's clients remain almost speechless for what the architect and friend was able to create, proud to have a house not only suited to their lifestyle, but also capable to pulsate and transmit charismatic vibrations in every single detail, breaking the impersonal repetition of the neighboring suburban houses. The unusual shape will be a provocation for many, who will describe it in the most curious manners, comparing it to a bird cage, an apple, a flying saucer, a giant mushroom and so on, causing as a reaction from the Fords to post a sign on which they express their own disapproval of the properties of these detractors. The project, from the very first moments of its initial phase, had involved the whole neighborhood, catalyzing the attention as a real spectacle. Passers-by stopped and crowded the site to witness the processes that led to exceptional and absolutely unconventional achievements, often full of tailored-made customizations. The strange and unprecedented appearance tickled the keen interest of some, dismaying others. Goff had always clients who were very confident in their preferences and choices, who, regardless of the public's judgment, appreciated his vivid imagination, high quality craftsmanship and the warm intimacy of their residences.

Interior of the Bavinger House, in Norman, Oklahoma. 1950. Designed by Bruce Goff for Eugene and Nancy Bavinger. Photograph courtesy of Anthony V. Thompson.

In 1950, Goff designed his iconic, stunning Bavinger House, in Norman, Oklahoma for two artists, Eugene and Nancy Bavinger, an earthy, monumental, fairytale-like house rising from the dense vegetation of the surrounding forest. It avoids any previously used architectural stereotype or layout, conceptualizing a logarithmic spiral over 96 meters long similar to a large Nautilus, which winds around a tall steel rod, rising into the sky. The spiral expands outwards with the wide volute of a wall, made of locally collected sandstone and rubble, mixed with clusters of large irregular blocks of solid glass in a blue-green hue. The interior space is completely open and kind of floating notes, at different levels, rhythmically punctuate its dynamism. They alternate like large, enveloping suspended nests around the central tree, dominating the three floors void, and, accessible by stairs that grow along the perimeter wall, welcome in their large circular concave surfaces. They offer five living areas, respectively in an ascending position: conversation, bedroom and study area. A soft carpet, in the warm shade of yellow, covers these pods, as well as foam padding, protrusions and recesses, which more organically replace the absent furniture.

Interior of the Bavinger House, in Norman, Oklahoma. 1950. Designed by Bruce Goff for Eugene and Nancy Bavinger. Photographs courtesy of Anthony V. Thompson.

Virginia Cucchi

Credits:

Photo: Cover, 3, 5-8 Bavinger House e 10, Model of the Ford House, 16- 17 Ford House : Photographs courtesy of Anthony V. Thompson, to see more of his photographic work of Bruce Goff's projects: https://flic.kr/s/aHsiS2Yxmn

Photo: 1: Bruce Goff in his studio at the University of Oklahoma, 1954, Photo of Philip B. Welch. Courtesy of Goff Archive, Ryerson & Burnham Archives, The Art Institute of Chicago; digital file @ The Art Institute of Chicago,

Photo 2 : Bruce Goff and Frank Lloyd Wright, Courtesy of Goff Archive, Ryerson & Burnham Archives, The Art Institute of Chicago; digital file @ The Art Institute of Chicago

Photo: 4, 9 Bavinger House : Photographs courtesy of Michael Stano.

Foto: 11-15 Ford House: Photographs courtesy of Rachel Cole, to see more of her photographs of Ford House: https://flic.kr/s/aHsjGRikMJ