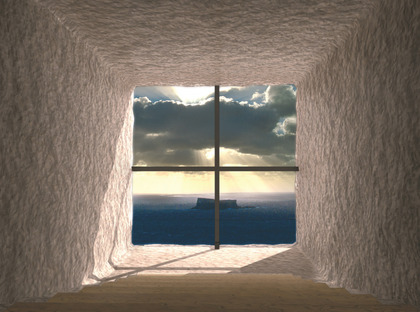

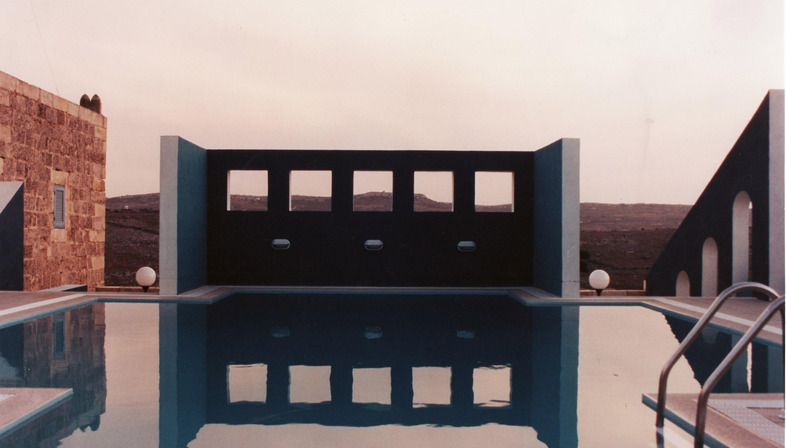

The architect, friend of my father, who spoke with such passionate intensity and poetry about silence is Richard England. He lives on an island, Malta, where he was born, a geographical situation that could have influenced his particular propensity for an architecture of meditation, an architecture 'to feel more than to watch', just as Luis Borges pursued, in the last years of his life, continuing to travel, although plagued by complete blindness. In reality Richard has lived a life, full of very interesting and important encounters: graduated from the Polytechnic of Milan, in the 1960s, a period that he loves to define the 'golden moment' of Italian architecture, he practiced in the studio of Gio’ Ponti, at that time editor of Domus magazine. The atelier was an opportunity to meet exceptional personalities, men of the highest artistic and moral caliber, who refined the predispositions and nourished the enthusiasm of a young man, who already intended the chosen discipline as a vocation, with the commitment to continue the profession of the father, an architect too. Albini, Michelucci, Mangiarotti, Scarpa, Giancarlo De Carlo, Moretti are just some of the giants with whom he had the opportunity to confront, and even to work, as when in 1961 Ponti was entrusted with the interior for the Palace of the International Labor Exhibition in Turin, assigned to Pier Luigi Nervi.

About these men of profound culture, able to animate the debate of Italian architecture, Richard often remembers with great admiration the humility and modesty that so much impressed him of Nervi, qualities that will be a constant for him in his profession and in life. Returning to his island, he began with small interventions, until the working horizon opened up to a more international panorama: in the ‘70s he worked in Saudi Arabia and in the early ‘80s along with Robert Venturi, Arup Associates, Arthur Erickson, Sheppard Robson and Ricardo Bofill as consultant to the Mayoralty of Baghdad, Iraq, on the rehabilitation of the city.

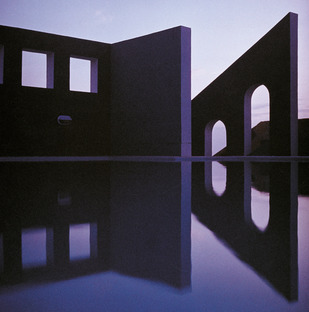

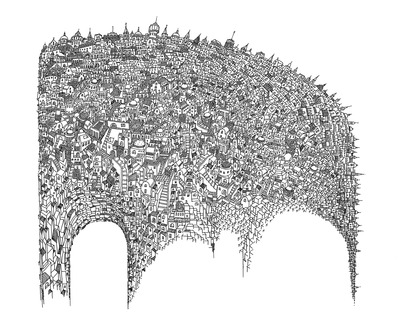

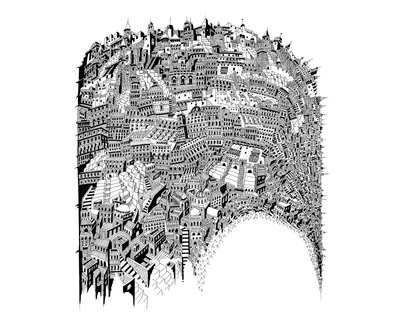

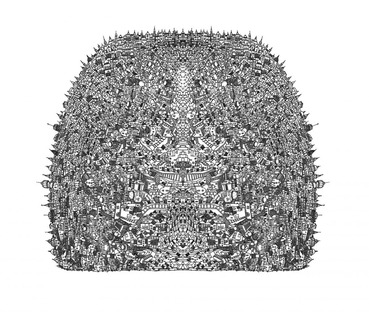

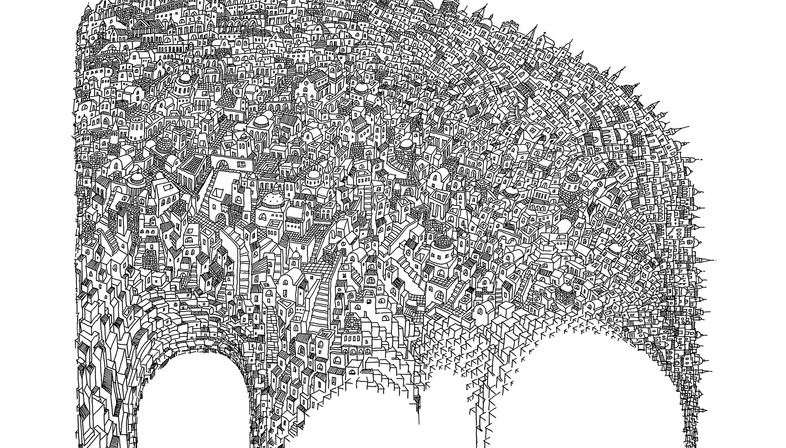

He supported the attempt to reactivate the relations with Renzo Piano, in defense of the controversial, disputed masterplan proposed to renew the original and historic features of the existing Valletta site, claiming that “ditching Piano would have gone down in history in the same way as if the Knights had thrown out Caravaggio's paintings!" and that the project would have represented "a Valletta’s beacon for the future. A masterly combination of elegance and strength. An excellent entrance with wonderful lateral staircases”. The architecture of Richard England starts from a careful analysis of the rich Maltese vernacular stratification with the precise intention of "adding a leaf to the tree, but not replacing the whole tree". Among the three Vitruvian principles, what intrigues him the most is the concept of ‘Venustas’, interpreted as beauty and poetry. The literature confers to his projects a magical aura, helping to search for a more abstract, metaphysical dimension. "My business is to weave dreams", to quote Luis Borges again, author much loved by him, but it could be his own statement about the purpose of his profession.

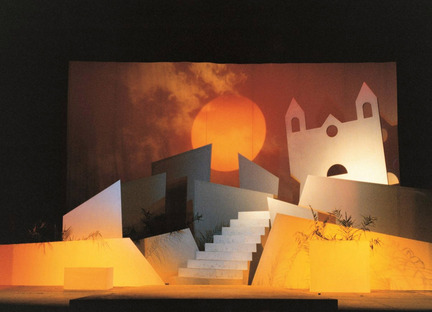

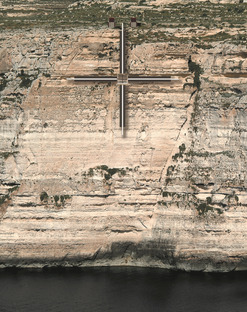

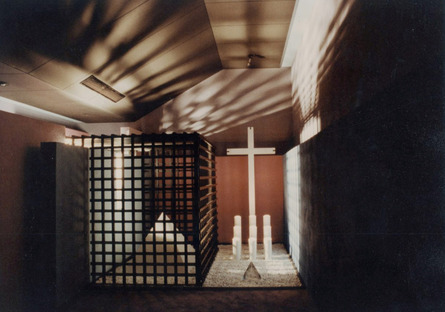

Very much involved in the theme of religion, he designed several churches, aiming to reach the sphere of spirituality, through an expression based on essentiality. He devoted himself to teach and received important recognitions such as 8 Honoris Causa by the Universities of Buenos Aires, New York, Georgia, Sofia (3 universities), Romania and Malta, and many other prestigious awards. Just in these days he has been honored by the CAA Robert Matthew Award. He is not only an architect but also a sculptor, photographer and exquisite designer. He claims to love poetry but he is a poet himself. Extremely cultured and sagacious, he knows how to find expressions that make us smile in their truth, as when ironically he talks about architects and says they should "have more eco than ego". Recently he refers to his island with a bit of bitterness, saying that from uncontaminated virgin, it has been unfortunately transformed into a whore and regrets that today's architecture has become too venal, too attentive to the economic profit.

The answers I received were so generous and interesting that I decided to divide the interview into three parts, to not deprive the reader of absorbing them with voracious pleasure and the reflection they deserve.

- Richard, I once heard you talk about silence with so much intensity and passion, to trigger a strong desire to explore the theme of great fascination. I would like to ask you why you have made this element such an important part of your work and, I think, also of your philosophy of life.

SOUNDSCAPES OF SILENCE

“Much silence makes a mighty noise”-- African proverb.

SILENCE AS CONTEMPLATION

Dictionaries define “silence” as “absence of sound or noise”. Yet silence is much more than an absence or void, and there are as many kinds of silences as there are sounds. I personally consider silence as the primary essential quality for contemplation, tranquility, rest and calm; all so necessary in today’s clutter, urban chaos and frenzied assault of technological gadgets. It remains perhaps the best antidote for a contemporary digital detox, a form of what St John of the Cross referred to as “mute music”. Silence may also be thought of as a light, which illuminates what is in shadow, for silence, actually speaks, and can at times be a language more powerful than words. “The learning of a language is more about the learning of its silences than its sound” (Ivan Illich). There are times when absence is even more potent than presence (think of the Twin Towers). Perhaps silence may be thought of as the lost echo, ghost or phantom of sound.

Human life is but a turbulent interval between two profound silences, that of the pre-natal womb and that of the post mortem grave. Silence involves a change in the tempo of our lives, a leap into limpidity and lucidity. Have we not all experienced the most rewarding moments of silence when after you close the door and you are alone, you experience an elegiac instant, when the gentle breeze of stillness ruffles the chaos away, cuddles the body, calms the mind, reposes the soul and composes the spirit? Above all silence acts as a primary source for cleansing, even more of a necessity in our contemporary world of materialism, monetary greed, competition and the endless barrage of machines and media. Jean Arp’s words “man has turned his back on silence” are even more true today, than when the artist wrote them nearly a century ago.

What is required today is not an empty silence but one which is pulsating and poignant; one which stills, heals and comforts. It was George Steiner who reminded us that “silence is a refuge”. Today’s secular and technological lifestyle precludes silence. We live in an age of clamour and noise and what we need is not the ever increasing resonance of sound but a restful calming silence. In 2011 the WHO defined noise as “a modern plague” and confirmed that noise had adverse effects on our health. Silence today has regretfully become an endangered species, yet it is still a basic necessity, for it can in the words of Persian poet Rumi “take you to the core of life”, as it is a catalyst for inner rapture and exultation. The same poet’s words “all is known in the sacredness of silence” once again emphasise the importance and necessity for silence to overshadow and overcome sound. Today it is a necessary task to pacify and placate the deafening screams of modern life, for silence nurtures and protects; its pastel leaves embrace, its docile hues caress and its sacredness envelops. It was Kahir Gibran who reminded us that “only when you drink from the river of silence shall you indeed sing”. Silence without creates silence within, for more than a void it is a fullness that is potent enough to drown the loudest clamour. Silence may also be thought of as the orb of sound, a dawn rather than a twilight, a beginning more than an end, or in Louis Kahn’s words “a threshold where silence and light meet”. Yet silence also shares a paradoxical relationship with sound. Ultimately external silence breeds inner silence. Perhaps the loudest silence of all may yet be the silence of death. To find out we just have to wait!

SILENCE IN ANTIQUITY AND THE BIBLE

“He approaches the gods, nearest to gods who knows how to be silent”—Cato the elder

The phenomenon of silence has been a much discussed and debated subject since antiquity. Most ancient civilisations harboured deities of silence; the Egyptians Horus, offspring of Osiris and Isis and god of the sun who was later interpreted by the Greeks as having been the god of silence because of the placing of his fingertip on his mouth. The Greeks themselves worshipped Harpokrates (derived from Horus) as their god of silence and secrecy, while also believing in a spirit of quietude Hesychia. The nymph Calypso, daughter of Atlas, who dwelled on the island of Ogygia (Gozo) was also according to Greek mythology, as recounted in Homer’s Odyssey, a deity of silence. She is reported to have kept Odysseus a prisoner on Ogygia for seven years until ordered to release him by Zeus. The Roman Goddess Angerona also held her finger to her mouth as if requesting quiet and was also considered a deity of silence.

Among the many references to silence in the Bible, the New Testament recounts that Jesus always visited silent remote locations to pray “…Jesus went off to a solitary place, where he prayed” (Mark 1:35). The apostle Matthew in his gospel recommends silence as an essential quality for prayer with his words, “Go into your room, close the door and pray to the Father in silence”. In the ‘closing’ of the door Matthew is suggesting the elimination of the clamour of everyday life and the necessity of silence for prayer. In fact it is in silence that prayer is most potent, for ultimately prayer is more about silence and listening than asking. It was the American pastor and author Aiden Wilson Tozer who said “if you do all the talking when you pray, you will never hear God’s answers” and Mother Teresa also reminded us that “God cannot be found in noise and restlessness, for He is a friend of silence”.

OTHER ASPECTS OF SILENCE

“Since long I’ve held silence as remedy for harm”—Aeschylus

Silence is perhaps at its most powerful as a pausing threshold to creativity. It was Thomas Carlyle who said “silence inspires creativity” and Einstein confirmed that “the solitude of a quiet life stimulates the creative mind”. In the disciplines of both Science and the Arts we find examples of how silence not only kindles the fires of the creativity in the minds of the makers but is also at times present as a key component of the created project itself.

Silence can however also have different uses as for example when it functions as a necessary pause when one ponders on how to respond to awkward questions; when it functions as an attentive pause to listening, or when it is utilised as a weapon of protest. It is also manifest as a basic consolatory aspect for individuals experiencing grief and sorrow at the demise of loved ones. It was Voltaire who said “tears are the silent language of grief”. The healing path primarily necessitates seeking refuge in solitude and silence as silence remains the best palliative and solacing antidote at times of bereavement and loss. Truly silence placates grief and is an alleviating song of mourning. It is also utilised to remember tragic incidents or victims in the observation of “a minute of silence”.

SILENCE IN MUSIC

“The notes I play like anyone else, but the silence is in between, that is where the secret lies”—Arthur Schanbel.

Silence in music determines the spaces between the sound, it is there to serve the sound. Musical pauses are referred to as intervals, equivalent to punctuation in literature. “There is a silence before the note, there is a silence at the end and there is a silence in between” (Daniel Barenboim). Musical composition elevates silence to the same level of importance as the played notes. Handel, Mozart, Beethoven, Wagner and others all utilised long musical pauses or rests to enhance the sonic sounds. It was Mozart who said “the music is not in the notes but in the silence in between”, and conductor Leopold Stokowski later added that “a painter paints on canvas but a musician paints on silence”. Elongated intervals in music may be termed as expressions of the inexpressible and are often found in major classical works to further extend and amplify the silent pauses between the notes. Examples abound in compositions by such composers as Sibelius, at the end of his Fifth Symphony, Haydn in his Creation, and Barber in his Adagio. Specifically elongated intervals are present in the work of the Japanese composer Toru Takemitsu who in his later works based many of his compositions on the Japanese concept of MA (voids which are not empty or absences which are presences) as a series of pauses to create not only silent voids but also extensive moments of reflective meditation. The Estonian composer Arvo Part is also concerned on how spaces of silence in music actually increase its emotional power. His silences create rapturous intervals of seemingly mystical and spiritual stillness. ‘Fur Alina’, one of my favorite pieces of this composer is a composition pregnant with an abundance of extended, meditative silences. It is a work of naked minimalism and ineffable beauty, an ode to the interval spaces of silence between the notes.

The American composer John Cage made it his mission, in an endless search, to experience complete silence. In his constant probing he entered an anechoic chamber (an echo free non reverberating room) in the hope of hearing absolute and complete silence. However the experience did not provide him with absolute silence. Instead in Cage’s own words “I heard two sounds, one high and one low, the former that of my own nervous system in operation and the latter my blood circulation”. After his anechoic chamber visit, Cage concluded that “try as we might to make complete silence, we cannot”. It was after this that he composed his controversial 4’33” consisting solely of silence. It was a composition which changed the history of music; a work inspired by the blank canvasses of fellow American artist Robert Rauschenberg and the philosophy and writings of the Dada artist Marcel Duchamp. The object of the composition was to again emphasis that absolute silence is impossible to attain. Cage recounts that 4’33” was not in fact silent, but full of all the surrounding ambient noises which the audience would experience and which he considered as integral ingredients of the musical piece; sounds not created by the composer. Cage’s major influence apart from Rauschenberg and Dada was his interest in the philosophies of Buddhism and Zen. His intention was to provide listeners with a four and a half minute respite from forced listening; an attempt to restore for some short moments the lost silence in our loud shrieking world. Despite its controversy it remains a piece which makes a powerful and potent statement. It emphasised more than any other composition the fact that silence in music is as important as sound. “Music and silence combine strongly, because music is done with silence, and silence is full of music”, Marcel Marceau. One of my favourite passages in prose relating to the silence of music comes from Norton Juster’s The Phantom Tollbooth. The book which is composed in a text of ear-tickling word play, manifests Juster’s belief that there are as many silences as there are sounds. The chapter for which I have a particular penchant is the one where Chroma conducts not aural music but the silent inaudible changing colours of the sunset, a soundless, noiseless, aphonic symphony.

SILENCE IN POETRY AND LITERATURE

“Poetry is painting which speaks”—Plutarch

In prose it was the Nobel Prize Laureate playwright Harold Pinter who considered the pause of ‘unspoken dialogue’ as important as the words. In his works he made use of silent pauses to create either a sense of hesitation or tension. Pinter always firmly believed that communication is not only achieved by what is said but equally by what is unsaid. Poetry, the music of language, is about building, building with words and sculpting with sound and silence. It is about the taste of words and their intermittent voids and silent pauses; a cross-over between sound and silence. One reads not only what is written, but also that which is not written; the words between the lines and the invisible words too; the heard and the unheard; the said and the unsaid. It is how musical and meaningful the poet can make these passages that elevate his or her work from the realm of prose to that of poetry. The true poet is the one who casts a web of magic that has the capacity to carry the reader away and cap human emotions in order to lift up the hearts of its readers. As a mythical sorcerer and mystical cartographer the poet threads outside the realms of time and space. In the poet’s mansions of magic and myth chronicity is no longer the norm, longitudes and latitudes merge and memory and oblivion dissolve into the mirrors of legend and lore. When writing poetry one needs the silence in order to hear the sound of the words.